Benjamin Wang - NanoJapan 2014

Rice University

Major: Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering with a Minor in Biochemistry and Cell Biology

Class: Sophomore

Anticipated Graduation: May 2016

NanoJapan Research Lab: Maruyama-Shiomi Lab, Prof. Shigeo Maruyama, University of Tokyo

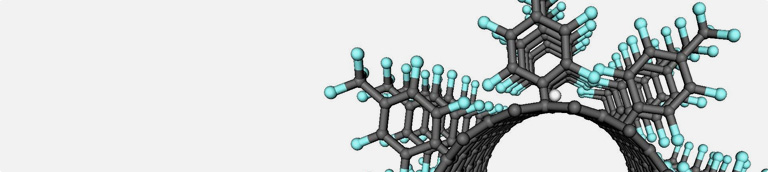

NanoJapan Research Project: ![]()

Why NanoJapan?

I believe that cross-cultural research experiences have the potential to do two things: they produce multidisciplinary, globally-minded students that can communicate effectively across national boundaries with professionals of many disciplines, and they enrich research by combining innovations and resources from multiple institutions. For me, Japan would be the ideal setting to develop these communication and professional skills. NanoJapan would both cultivate a sense of cosmopolitan multi-dimensionality and help me develop my current scientific interests. Moreover, it will provide me with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to construct lifelong relationships with foreign friends also excited about nanotechnology and the THz “gap” by enriching my personal values of teamwork, ethics, reasoning, collaboration, communication, and leadership.

Additionally, I am especially excited to understand a Japanese student’s perspective on his or her education and his/her everyday life in general with regards to school schedules, hobbies, and interests outside of science. While I have never learned the Japanese language in a formal educational setting or experienced its history or culture for more than a couple of days, I am eager to discover its one-of-a-kind traditions, people, educational emphases, and technologies through partnership and discussion with its residents, scientists, and students. NanoJapan will hopefully transform me into an internationally-minded, respectful individual, and enrich my skills in group collaboration and interpersonal communication.

My goals for this summer are to:

Research Project Overview at the Maruyama-Shiomi Lab, Prof. Shigeo Maruyama, University of Tokyo

For my research internship with Maruyama-sensei, I will be studying the synthesis of single walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs). SWNTs are unique because they can exhibit both metallic and semiconducting properties depending on the diameter and chiral angle of the nanotube. As a result, such materials are highly desirable for their numerous potential applications. Single walled carbon nanotubes are one-dimensional and consist of a band gap that ranges from approximately 0 eV to 2 eV. Furthermore, there are a variety of different synthetic techniques for SWNTs currently available, including HiPco, CoMoCAT, Laser Oven, Arc Discharge, and CVD. For my project, I will mainly be studying various synthetic techniques for SWNTs. More specifically, I will be looking at the synthesis of SWNTs through growth on various Fe-, Pb-, and Cu- based catalysts. Through the use of these catalysts, my work will involve attempting to modulate vertically aligned SWNT properties, including morphology and size, chemical chirality, and distribution. However, my project will also include characterization with electron microscopy and various other spectroscopy techniques to measure chirality. The ability to modulate such properties of SWNTs makes them useful for a variety of practical applications. These include solar cells, thin cellulose-based batteries, and bio-mimetic hierarchical composite materials, such as collagen-mimetic hydrogels.

NanoJapan 2014 students during the Pre-Departure at Rice (left) and upon arrival at Narita Airport in Tokyo (right).

The first thing I noticed during my first night in Japan was how quiet everything was—people on the streets spoke to each other quietly, cars weren’t honking their horns, and young children weren’t yelling or crying everywhere I went. The second thing I noticed was how involved everyone was with his or her smartphone. On escalators, in subway trains, and at crosswalks, the majority of people were buried in their smartphones. Before arriving in Japan, I expected cleanliness, vending machines, and lots of lights. This was true for the most part in larger districts such as Shinjuku, Harajuku, Shibuya, and Akihabara. However, smaller districts like Azabujuban and Hachioji were more quaint. I also thought it was interesting that the bigger districts were larger and more populous than some of the large cities I have lived in in America. For example, there were more people walking the streets in Harajuku than I have ever seen in all of Houston or Dallas. Moreover, each of these districts seemed larger than all of downtown Houston or Dallas. Another thing that shocked me was how safe I felt in the city late at night with so many people around me (except for Roppongi; that place was pretty sketch). I never had the fear of getting pickpocketed or robbed even when I was by myself, and people were always willing to give directions. Even though we got lost just about every night during the first week, we were sure that we would get home safely.

Shibuya Station: First full day in Tokyo and I’ve never seen so many people on the streets

My experience with the KIP (Japanese) students this past week was also notable. We met on Wednesday night during the first week to discuss the ethics behind genetic engineering. Initially, I thought that the language barrier would prevent us from discussing anything in depth, and I was nervous to meet them because I was afraid that they might have had negative attitudes towards gaijin. Surprisingly, however, their English skills were remarkably good for college students (some who had never been to America). We were able to discuss the topic in great detail for an hour and a half before we ran out of time. All of the students had new and different ideas that were intriguing and refreshing to listen to. I especially enjoyed the discussion because the Japanese students were able to offer ideas that challenged my and other NanoJapan student’s American-taught perspectives. Additionally, I enjoyed speaking to the KIP students because they too were eager to speak with people from another country. I found the eagerness of both sides to learn about each other as well as the radically different ideas from students with different educational and cultural backgrounds especially fruitful.

Overall, my first week in Japan was great. Contrary to my initial expectations, I have found that Japan is very accommodating to outsiders, whether in speaking the language, preparing foods that suit each of our dietary needs, or giving help if one of us is in trouble. There’s always something to do in the city—even in the middle of the week—and some of the quieter areas like Kamakura are fun to explore. I am very much looking forward to my stay in Kyushu this weekend and working with Japanese high school students, as well as moving to my lab at the University of Tokyo a few weeks from now.

Sumo: First time at sumo and it’s packed!

In addition to exploring the city, daily 3-hour language classes have been difficult yet rewarding. Each morning, we make a 20-minute walk from the Sanuki Club Hotel to the AJALT offices in front of Tokyo Tower. The most difficult thing about language classes is the sheer amount of vocabulary we learn each day, as well as how quickly we move from unit to unit. Each day, we probably learn the same amount that would be taught in an entire week from a college-level introductory language class. However, I enjoy going to language classes every morning. The AJALT instructors are understanding and accommodating, and classes are very small (4 people/each) so there is a lot of individual attention. We usually go around the table and each person will verbally repeat the phrase/word we are learning at that time. This helps me learn the phrases much quicker. Additionally, the daily homework helps the learning process—they usually only take 15-20 minutes and go over phrases, sentence structure, and vocabulary that we learned that morning.

Living in Japan also makes learning the language much easier, as we are able to use the phrases and vocabulary we learn on a daily basis. In the first week, we learned how to introduce ourselves in Japanese, buy things from the konbini (convenience store), how to ask to look at items at clothing and electronics stores, how to order food at both restaurants and fast-food places, and how to ask for directions. In the first week, I was able to practice to all of the things I learned—I purchase bento lunch daily from the nearby kombini, have gone shopping in Shinjuku, Shibuya, and Harajuku, and get lost in the subway station almost daily. One thing I did not expect was that many Japanese people know English—the KIP students told us that they learn English starting from Junior High School (6th grade in America I think), and need it for the rigorous national college entrance examination. Sometimes, when I speak to someone in Japanese, they can tell that I have an American accent and speak back to me in English. While it’s a nice that I can communicate in my native language, this makes practicing my Japanese difficult at times.

To help my Japanese skills progress, I am always actively working to speak in Japanese outside of class. I also spend my free time on subways or at restaurants waiting for my food trying to read Hiragana and Katakana. While I have all the characters memorized, it’s still difficult string together characters. It’s also very difficult to read words and phrases in Hiragana and Katakana quickly.

Ka-ma-ku-ra: I chose this picture because it captures both my visiting of Kamakura as well as me learning Japanese

The biggest question I have so far with living is Japan is the language barrier and the fact that I am Chinese-American. Often times, I feel like I am expected to know how to speak Japanese because I look Asian. For example, when exploring Roppongi the first night with the other NanoJapan students, I was approached by people on the street advertising their restaurant or store on numerous occasions. Because I still cannot speak conversational Japanese, I don’t understand what they are saying so I just look at them blankly. It quickly becomes very uncomfortable for both parties. Additionally, this past Sunday, when I went to Kamakura with the other NanoJapan students, I was never asked or given any of the English fliers/descriptions/maps after paying my entrance fees for the temples. This was a bit strange to me because I was in a group of many non-Asian-looking people, yet I was never asked whether I could read Japanese or not.

Intro to Nanoscience Lectures

Prof. Kono’s Intro to NanoScience Lectures gave an introduction to some of the overarching principles behind all of the projects, including materials science, quantum mechanics, and solid state physics. I found it helpful that these lectures talked a little bit about each of the projects that will be happening this summer, as well as the fundamental material behind them. However, some of the lectures were a bit more difficult for me to follow because I have only taken two semesters of introductory level college physics.

In the first week we visited five labs at Todai, Elionix, and had a lecture from Dr. Fon of AIST. I found Paul Fons’ lecture especially interesting because he was able to intertwine his research interests, goal, and work with cultural aspects of living in Japan. He was able to give us a good introduction to what we should expect from our labs in the coming weeks. I also enjoyed the visit to Elionix and the innovative technologies they had with electron microscopy and the other characterization instruments they produced.

As my second week in Japan comes to a close, I’ve been able to experience both the subway system and a couple of late night taxi ride back to Azabajuban. The only other public transportation system I’ve used regularly is the Houston METRORail system. Very quickly after arriving, I noticed that passengers in Tokyo’s subway system were almost all silent. Not a single person was talking to another person on their phone, and if passengers were conversing with each other, it was done at a whisper volume. In contrast, on Houston’s Lightrail, I regularly found people talking loudly on their cell phones, or talking very loudly with the people right next to them. For the past few weeks, I have very much appreciated the consideration people have for one another in public spaces. Another thing I noticed regarding the level of noise on public transportation was that parents made sure their children were quiet. Very rarely did I hear a child crying on the subway in the past two weeks. However, this was a regular occurrence on the Lightrail in Houston.

The most packed I’ve ever seen a subway train!: Luckily, we were going the other way, but this is the most packed I’ve ever seen a subway train. One of the KIP students saw this picture and said that it was a regular occurrence during rush hour.

In addition to their attention to the noise level, the passengers on Tokyo’s subway system are very conscientious of space in the trains. At busy times (before 9:30 AM and after 4:30 PM), no free space is wasted—trains are usually packed to the point to which people are pushed up against each other. During rush hour, people continue to pack the trains even though they are clearly full. However, I’ve noticed regardless of the time, the seats are always filled up first—both men and women young and old use the seats, and from what I’ve seen, seats are largely taken on a first come first serve basis. I’ve only seen younger people give up their seats for older passengers in the designated priority seating zones at the edges of each train. Initially, I imagined that younger people would be quick to give up their seats for older passengers. From what I have seen, however, this is not entirely the case. In fact, Naoki-san told us not to give our seats up to other passengers because it can be interpreted as offensive. A humorous and awkward moment occurred when Vernon and I disregarded Naoki’s advice. I told Vernon to ask the visibly tired passenger if she would like his seat, but when he did, she declined and did not sit down. Vernon did not want to sit back down either, so they stood next to each other for a couple of seconds both staring at the empty seat. I noticed a Japanese man sitting next to me started laughing at the situation, and he said to us in English, “Ask the girl behind her if she wants the seat.” Vernon did what he suggested, but she also didn’t want to sit down. Finally, I asked Vernon if he thought I should stand up too, and he said yes. For the next few stops, we both stood next to two perfectly good open seats that no one wanted.

In contrast to Tokyo’s subway system, Houston’s Lightrail usually doesn’t have enough people riding the train for all the seats to be occupied, even during rush hour. On the subway system in Tokyo, there are usually very few activities that people engage in. Younger passengers usually have their smartphones out while listening to music/watching a show/playing a game. Older passengers usually spend their time reading a copy of the newspaper or a book. Finally, the majority of people are dozing off or staring off into space. One common feature of each of these activities is that they are all individual, and do not affect the people around them, such as making phone calls, talking to other passengers, and eating/drinking. As a result, the trains are always clean, tidy, and quiet.

While trains can easily become very, very packed, all passengers understand that like themselves, all other passengers would also like to get to their destination as quickly and painlessly as possible. As a result, people work together to make the ride as painlessly as possible: when the trains stop to let passengers off, people sitting closest to the doors will temporarily step outside of the train to let the more inside passengers out. Additionally, passengers getting on the train will make a single file line to the left and right of the train and allow all passengers to get off first before getting on. Thus, time spent at stops is minimized. I’ve also noticed similar behavior on elevators in Japan. This behavior is very different to what I have experienced with public transportation in the US. Usually, people try to enter as soon as the doors open while people are still exiting the trains making the sopping process slow and painful.

In addition to being conscientious of other passengers, the vast majority of public transportation passengers in Tokyo are very polite—almost always, people will say sorry, or sumimasen, after bumping into each other. From these observations with Japan’s public transportation system, I believe that cultural differences largely fuel the efficiency of the Japanese subway system. In contrast to the United States where people are more individualistic, the Japanese exhibit more of a collective awareness. Because people understand that all individuals have similar problems and desires, they can work together to make their lives as efficient and problem-free. I think this is demonstrated very well by the unwritten procedures for boarding and exiting the subway trains. In addition to this, I think another part of Japanese culture—empathy for others—is exhibited with the Japanese subway culture when passengers make sure to excuse themselves or say sorry when they accidentally bump into one another. Additionally, I’ve noticed that instead of leaving their bags or backpacks on their person or putting them on the ground, passengers usually take off their bags and place them onto the overhead racks to allow for more people to enter the train. I think this awareness for the well-being of others is also distinct from US culture.

Okonomiyaki: I tried Okonomiyaki with the KIP students after our discussion about the environment. It was great!

Overall, my second week in Japan was just as good as the first. While I wasn’t able to explore as many places due to the packed schedule and upcoming assignments, living in Japan has still been an adventure. This week I visited the Pokemon center in Daimon, went back to Shibuya and stumbled upon Ginza while purchasing omiyage for my host family in Kyushu. I am continuing working on using the Japanese I learn in class in my daily activities, but it is getting much, much harder. I am also continuing to research and read journal articles about my research topic in preparation for the second half of the program. I am very much looking forward to it!

Ben Foust fell asleep on the floor of the 3rd floor seminar room after a night exploring Tokyo: Days are long, nights are even longer, and sleep is short.

Intro to Nanoscience Lectures

This week, Prof. Bird presented two lectures on semiconductor bandgap engineering and graphene’s impact on nanoelectronics. For his first lecture, Bird-sensei demonstrated how advances in the production of semiconductors were responsible for the technological revolution we are living in today. From these lectures, I thought it was most helpful that Bird-sensei started each lecture with practical applications. After introducing the applications, he introduced the topics of the talks (bandgap engineering and graphene). He was also able to introduce the topics in such a way that I was able to follow without being taught the material previously in a college course.

This week, we also had two guest lectures from Professor Maruyama from the University of Tokyo and Prof. Ishizaka also from the University of Tokyo. Professor Maruyama discussed his group’s work on the synthesis of carbon nanotubes and his recent work in developing graphene synthetic techniques. In addition, he also discussed the project that I will be conducting this summer for my research internship. I will be studying different techniques for carbon nanotube synthesis, as well as different methods to modulate the morphology of the synthesized tubes. In addition to this, I will be working to produce air-stable high-efficiency solar cells using films of single walled nanotubes. Professor Ishizaka also talked about her research as the first female scientist at the University of Tokyo’s Department of Applied Physics. In addition to her research, Ishizaka-sensei also talked about the issues surrounding women in science in Japan. She presented many interesting experiences about being the first female faculty member in her department, as well as what made her want to become a scientist as a child.

During my trip to Kyushu, I was able to experience living in rural Japan for the first time. The first thing I noticed when landing at Kumamoto airport was how much more spread out everything was compared to with the city streets. Additionally, the abundance of agriculture also caught my attention. On our way from the airport to Aso-san, we saw rice paddies, vineyards for local wine making, and tea leaf farms. In the rural part of Japan, it was also interesting that all people seemed less in a rush, and more interested with what they were doing at that moment. I first noticed this with the instructors from Gokasee Secondary High School who came a picked us up. When we met for the first time, each of the instructors shared introductions of themselves right in the middle of the airport. They could have easily waited until we were on the bus to share introductions, but there was no rush to get on the bus as soon as possible.

On the first day, after landing, we visited Mt. Aso and a local kindergarten. The bus dropped us off at the top of Mt. Aso, and we were able to walk all the way to see the smoke coming from the volcano. We had to leave early, though, because the smell of sulfur was too strong and they said it was bad for us. After leaving Mt. Aso, we visited the local kindergarten where we played Japanese duck duck goose, sang some songs, and make hand-print paintings. I was surprised by how well-behaved all the students at the kindergarten were—they washed their hands after painting and lined up orderly in single-file to do so, they were quiet when the teachers called for their attention, and they each shook all of our hands before we left. In America, I would not expect such orderly and respectful behavior. I think that this difference is a product of both different methods of parental upbringing, as well as the different education emphases of each country. The American education system focuses more on individual success, while the Japanese education system emphasizes collective problem solving and thought.

That night, after the kindergarten, we visited a shrine and watched traditional Japanese Kagura. Like sumo, I found it interesting that Kagura focused much more on the ritual of the activity, rather than the presentation itself. One of the mentors that accompanied us told us that Kagura was traditionally only preformed during the winter months, where dances would occur from late at night to late morning the next day. People would drink sake outside to stay warm, and then come inside to that night’s volunteer home to watch the dances. At both of these activities, it was also interesting to note the disparity between men and women. In the case of sumo, women were considered dirty and were not allowed to enter the ring (it’s cleansed by salt before each match). This posed a problem at one point when the mayor (whom usually presents the champion wrestler the prize) was a female. Eventually, she was replaced by the next in command male, who presented the prize. On the other hand, in the case of Kagura, only men are allowed to preform the dances. This becomes interesting when a male must play a female role. For example, the 4th dance that we watched portrayed a male and his wife getting drunk together off sake. The wife was played by a man. At Kagura, I also did one of those wish-predicting machines, where you pay 50 yen and a piece of paper pops out with your fortune for that year. Ben F. did it a couple of days earlier and got terrible luck, so I was hesitant. One of his fortunes said “a family member will get sick and not recover.” The KIP students read my paper and said I got above average luck, though, so I guess it was a success.

The next day, we visited Gokasee Secondary High School and made traditional waraji sandals, had lunch in the school’s cafeteria, then had a discussion session with the students, and finally concluded with a demonstration of how to produce a DC rotor from a battery, magnet, and wire. While waraji making was fun, it was more interesting to be taught something by Japanese students. For a brief amount of time, and with something very elementary, we were able to get a taste of Japanese educational values. Most importantly, even though I was a terrible waraji maker and it was difficult to communicate to the Gokasee students in English, they remained patient and were very attentive to the problems I had for the duration of the sandal-making time. I especially liked how they got so excited when I would ask what might be seen as dumb or silly questions in America. For example, the first step in making waraji sandals is to knot the ribbon and fold it over itself. Because there were two foot-shaped loops, I thought that the one ribbon made two sandals, but I wasn’t sure how we would detach them because we were weaving the loops together. In retrospect, I don’t know why I thought the two loops woven together could make two sandals. However, when I asked them this question, instead of giving me a funny look or laughing at my question, they enthusiastically gave me a big demonstration (signed, because I couldn’t understand the Japanese) on how we were making only one sandal at a time. I imagine this would have played out very differently at the high school I came from. I also thought the fact that the students at Gokasee even knew how to make waraji sandals was interesting. I think this also clearly demonstrates the Japanese emphasis on culture and tradition in their educational system. While Japan is one of the most technologically advanced countries on the planet, they still choose to teach their young generation how to make sandals made from straw from used centuries ago. In contrast, in the US, much more emphasis is placed on always being the first to innovate something new.

After lunch and waraji making, we sat down for a discussion about the economic impacts of environmental protection acts. From the discussion with the high school students, I found it was interesting that all the Gokasee students in my group wanted to present at the end of our discussion. In America, this is not usually the case—students shy away from public speaking and presentations. Moreover, the students at Gokasee were volunteering to present on a controversial topic in a foreign language. I also thought that for 15-16 year-old high school students, they all had a surprising amount of input into the discussion. This occurred even in spite of the partial language barrier, which I thought was amazing on the part of the Gokasee students. Finally, during the science demo, I thought it was cool how all Gokasee students were engaged and interested in completing the task at hand. Even when they did make the wire spin on the battery, they spent more time optimizing their designs. Most had already learned the right hand rule (the left hand rule in Japan) and had already made simple DC rotors in the past. However, in spite of this, they all still seemed interested in designing the best rotor among their peers.

At the end of our time at the high school, we each went to our separate home stay assignments for the night. Ben Foust and I were placed in the inn keeper’s inn for the night. When they picked us up, we went to a nearby fish farm and then had fish from the fish farm for dinner. The next morning, we drove up a nearby mountain to enjoy the scenery. It was a great experience living in a traditional Japanese household for a night. I got to understand Japanese familial dynamics and the attitude that everyone should contribute to the household. After eating my meal, I helped dry dishes with a towel—even though my task was as basic as they get, I still felt like I was able contribute to the household. This is much different to what I have experienced in the US: generally, my experience has been that hosts do not want their guests to do anything. I also noticed this attitude at many of the places I have eaten lunch at, including Todai and Gokasee High School—after finishing a meal, students are expected to clean off their plates into trash cans, and separate utensils and dishes by shape to be washed. After dinner, we chatted for a bit and I was excited by how interested my host family seemed to be at the seemingly very simple things I told them, such as the usual weather in my hometown and what I like to do in my free time. The fact that my host family seemed so interested in a gaijin surprised me the most, and I enjoyed telling them about America and Texas.I think the largest challenge I had with staying at my host family was the language barrier. While we did have a KIP (Japanese) student that could translate, I think it was difficult to capture the emotion from each individual when communicating. Despite this, however, my host family never got frustrated with my lack of Japanese knowledge, and seemed to enjoy listening to me speak English.

I think the most prevalent Japanese cultural values reflected on me by my host family was the attention to etiquette and harmony between them and us. They consistently made sure we were having a good time, and instead of declining some of our requests outright, they would say that “maybe it wasn’t possible,” or that “maybe it wasn’t a good idea.”

Overall, I truly enjoyed the Kyushu trip. It was a much needed change to the hustle and bustle of Tokyo, and I was able to experience the other more traditional side of Japan. I hope that I will be able to continue with similar experiences as my time in Japan continues and I am able to explore the country more!

Waraji making My partner for making waraji sandals at Gokasee Secondary High School. She made the left foot, and I made the right foot (the left was noticeably better). This was probably one of the most fun and interesting activities from the program so far!

Dinner from my homestay! I’ve never had so many different types of fish all at once—sashimi, fish on a skewer, soup with a fish head in it (not pictured), and fish egg paste (not pictured). All came from the local fish farm, and the meal was delicious! Raw fish has a very interesting texture that I’m not sure I’m a fan of. That yellow kiwi looking thing was also delicious too.

Everyone’s birthday dinner On the Thursday before everyone left, Packard-sensei treated us to a nice dinner at an Italian restaurant in Azabujuban. She said it was everyone’s birthday, so we could order whatever we wanted. This picture captures the great friends I have made just these past few weeks—I’m really sad to see them go, and I don’t know if I’ll be able to survive without Packard-sensei taking care of me.

Assessment of Orientation Program and Language Classes

Overall, I felt like the Japanese language training was the most beneficial activity from the Orientation Program. While it was difficult, it has been the largest contributing factor to my ability to live and work in Japan. I think the most useful part of the language classes was constantly conversing in Japanese for extended amounts of time. Additionally, going to a konbini during class and talking with native Japanese speakers was also helpful. I found that the most motivating thing when learning Japanese is how excited native speakers get when I say something correctly in Japanese. For example, during my first week in Japan, I said I wanted to order two items in Japanese, and the waitress gave me a very large smile and nod. As a whole, I found all activities that involved me speaking and understanding Japanese most useful. Additionally, exercises that involved reading hiragana and katakana were also very helpful. While I’ve had all the characters memorized for some time, it’s still very difficult to read strings of characters at a quick pace and understand meanings of words. In contrast, I found the homework assignments to be less useful (particularly the earlier assignments). In my case, the early homework assignments didn’t do too much to reinforce the material presented during class. This is because the homework did not involve speaking Japanese, and was written in romanji, so it did not reinforce reading kana. However, I found that the later homework assignments were more helpful because they were written in hiragana. This really helped my reading speed and ability to write characters.

To help me learn Japanese, I made an effort to speak as much as I could to native Japanese speakers. For example, at konbinis I would try to ask how much an item cost even if I could see the price on the tag. It was interesting when the clerks would respond in English after hearing my American accent. Additionally, at night, I would try to review that day’s material by going through the textbook. In class, because the teacher would often teach without referencing the book, reading the book though after the lectures would help me learn the material. It was nice to get a second perspective on the Japanese concepts being taught each day when I didn’t understand a certain topic. Finally, making flashcards for adjectives, nouns, and particles was helpful in learning their meanings. In one lecture, we learned probably 20-30 adjectives, and having flashcards to review them later on really helped. The most important thing I learned in my first 3 weeks in Japan is that most Japanese people do not mind if you are bad at the language. In my experience, it seemed that they only cared that I was making an effort to communicate with them in their language. Initially, I was worried that people would judge me for my poor Japanese, so I was hesitant to speak it frequently. However, I realized that most appreciated my effort when I did speak Japanese.

In addition to language classes, I found the cultural outings with the other NanoJapan students to be both fun and enlightening experiences. For example, I found it interesting that both sumo and Kagura dancing were more focused on the ritual surrounding the activity, rather than the performance itself. At sumo, for instance, it seemed that the actual fight was an afterthought compared to its preparation. Making friends with the KIP (Japanese) students through the discussions, outings, and the trip to Kyushu was also very fun. It’s nice to be able to ask a native Japanese individuals questions about how he/she was raised, cultural norms in Japan, the education system in Japan, etc. Having people that I know in Tokyo will also come in handy once everyone leaves for their respective labs.

As orientation comes to a close, I am still interested in Japanese workplace dynamics (but I’ll learn this quickly once I get to Todai), the norms for social interaction with strangers (for example in America strangers will often smile at each other or say “good morning”, but in Japan, it seems like most people shy away from interaction with strangers), and the must-visit places I should use my 21-day rail pass.

Research Update

This week, Stanton-sensei presented about the basic concepts behind photonics and optics science and technology. He talked about the potential applications for solar cells and photovoltaics, as well as applications for mass information storage. Additionally, Otsuiji-sensei presented about the various applications for Graphene Terahertz technology. Terahertz rays, for example can be used for imaging at airports and through materials such as the contents of an envelope. However, it is very susceptible to dampening by water vapor. As a result, long-range terahertz use is difficult to achieve. Other applications of terahertz radiation include wireless communications with a carrier frequency of ~500 GHz for a data transfer speed of approximately 24 Gbps. Graphene terahertz lasers have also gained much interest recently due to graphene’s unique optical properties.

The evening before my first day in lab, two graduate students, Sato-san and Takezaki-san, picked me up from the Sanuki Club. We took the Oedo line to my new apartment in Morishita, and after putting down my luggage and meeting with the landlord to pay my first month’s rent, we then went to Todai Hongo campus and had dinner in the area. I spent my first few days in lab reading papers and meeting my new labmates. On Tuesday, I was given brief a tour of the lab, and one of the members of the lab explained to me what I should expect to be working on this summer. For my first lab meeting, I prepared a couple of slides about myself and an explanation about some of the relevant research experience I have from Rice University. I did my self-introduction in Japanese, and everything research related in English. It was interesting because even though I completely butchered the Japanese, the rest of the lab members clapped after I finished my self-introduction. They did not clap a single time for the rest of the meeting. Maybe it was just because I was the new member of the lab, but I think they all clapped because I made an effort to speak Japanese.

For my project, I have two mentors: both are PhD students, but one is graduating in the next few months. So far, I have worked much more closely with the student that is graduating soon. He is Chinese, but speaks both English and Japanese very well. While he is very laid-back, he does expect a lot from people. For example, this past Friday, he taught me how to synthesize SWNTs by the chemical vapor deposition method. He then wanted me to try the entire process by myself the Monday after the weekend. I very much appreciate this because it shows that he trusts me enough to let me operate equipment that is crucial to the lab. All other members of the lab have been very friendly, and are always willing to assist me when I have questions. Additionally, even though some of them do not speak English very well, they do their best to explain things to me in such a way that I understand them. Apart from my lab mates, the professors in the lab are very accessible and easy to approach for any questions. For example, last week I had a discussion with Professor Chiashi about SWNT growth by simply walking up to his desk. Overall, I find working with the members of my lab very enjoyable. They are supportive of my questions and concerns and are very fun to talk to.

In my lab, the majority of students can speak English well. However, among Japanese students, Japanese is the working language. I don’t think this will be a problem, though, because most students are willing to translate what is being said. Among the few international students, English is used to communicate. The language barrier becomes difficult, however, during group meetings. During group meetings for our lab, each member gives a brief 2-5 minute presentation of what they have accomplished in the past week. Almost all presentations are given in Japanese, which makes it a bit difficult to follow what is going on most of the time. However, if something is said that affects other members of the lab, Maruyama-sensei will usually translate what is being said into English.

For my research internship at the University of Tokyo, I am living in a guesthouse close to Morishita Station. My room is about a 5-minute walk from the station. Both the Toei Shinjuku line and Toei Oedo line run through the station, making it very convenient to get around the city. To get to lab each day, I take the Toei Oedo line from Morishita Station to Hongo-sanchome station. The train ride takes approximately 10 minutes, and from the station, it’s approximately a 20 minute walk to my lab in Todai’s Hongo campus. Compared to my dorm room at Rice University, my room in Tokyo is very small! The room is about half the size of a single on campus at Rice. I found it interesting that the University of Tokyo does not have on campus housing. All students must commute to the university every day, which is very different from what is usually seen at American universities. According to a KIP (Japanese) student that is currently an undergraduate at Todai, this makes it very difficult to make friends outside of classes at university. At Todai, students usually make friends from their extracurricular activities, whereas at Rice, students usually make a significant percentage of their friends from their college (dormitory).

Overall, my first week in my research lab has been challenging yet exciting. So far, I have spent most of my time in lab familiarizing myself with the equipment. I have also spent a lot of time understanding the fundamentals behind my project by reading a variety of journal articles. However, the timeline and ultimate goals for my project are still a bit unclear. I have multiple graduate and PhD students mentoring me this summer, so sometimes is difficult to know who is taking the lead over me. I will be meeting with Maruyama-sensei this coming Wednesday after group meeting to discuss the timeline and specifics for my project though. Hopefully, by that time, I will have a working knowledge of the instruments in the lab so that I may start my project as soon as possible. Complicated instruments: Doing my best to learn how to use the CVD for SWNT growth. It’s been pretty overwhelming so far but I think I am slowly getting the hang of it!

Tokyo from the Mori Tower: Over the weekend, I went to the Mori Tower’s Sky Deck to see Tokyo from up high. This picture overlooks Azabujuban: if you look closely, you can see the Sanuki Club Hotel.

Cooking by myself: Since rent is expensive, I decided to try and save some money by cooking! It was my first time cooking raw meat, so my Japanese housemates told me what to do to cook the chicken. I bought all things seen on the table (except for the food scale) from the supermarket across the street. I made this dish because I like eggs and chicken (and I already knew how to scramble eggs and cook rice in a rice cooker), but apparently it’s a real Japanese dish. I was told it’s called Oyakodon—which literally translates to parent-and-child donburi. Donburi refers to the rice, while parent and child refer to the chicken and its egg.

Research Update

So far, for my project, I understand that I will be working on optimizing SWNT growth for use in solar cells. Kehang, one of the PhD students in the lab, has done much work on developing air stable high efficiency solar cells by using a honeycomb network of vertically aligned SWNTs. To do this, I will be looking at the synthesis of SWNTs using various bimetallic catalysts, as well as modulating various properties of the SWNTs. For example, currently, for CVD SWNT growth, our lab largely uses a Mo and Co bimetallic catalyst on a silicon substrate. I will be looking at using a Cu and Co bimetallic catalyst on the same silicon substrate to see how that changes the properties of the SWNTs, along with its effect on solar cell efficiency and performance. Moreover, I will also be looking at modulating many of the physical properties of the SWNTs to see their effects on solar cell performance. However, because I have spent much of my first week familiarizing myself with the protocol for SWNT synthesis and characterization, the specific outcomes and goals of my project are still unclear to me. I will meet with Maruyama-sensei this coming Wednesday to discuss the specifics of my project.

For my project, I will mainly be using the chemical vapor deposition method for synthesizing SWNTs. I will then characterize these SWNTs with Raman spectroscopy, photoluminescence, absorption spectroscopy, and SEM. During the first week, I was introduced to the drip coat method for preparing the silicon substrate with the bimetallic catalyst, CVD synthesis for SWNT growth, and the theoretical bases of Raman spectroscopy. This week, I will complete my own synthesis and characterization with Raman independently. I will then move on to characterization with SEM and other spectroscopic techniques. Additionally, for my project optimizing SWNT use in solar cells, I will need to learn the vapor deposition method for creating the honeycomb network of SWNTs. For this method, vertically aligned SWNTs are suspended upside down on top of a body of water. The water is heated, and the water vapor that evaporates upwards collapses some of the vertically aligned SWNTs to create a honeycomb network.

In addition to learning how to use the essential equipment for my project, I have spent a significant amount of my time reading past work both from Maruyama-sensei’s lab and other labs across the world on previous work regarding SWNT synthesis. One thing that I found both interesting and a bit frustrating about the field is that no one completely understands the mechanisms behind SWNT growth. Because of this, choosing different metal catalysts and altering growth conditions for the synthesis of high quality and high yield SWNTs is largely a trial and error process. This also holds true for modulating many of the physical properties of the SWNTs, such as length, diameter, and chirality.

Overall, the specifics of my project have yet to be established. In the coming days, after meeting with Maruyama-sensei and my mentors, I will send a follow-up research update with a detailed timeline for my project, as well as what I expect to complete by the end of my research internship.

On the first weekend after arriving in Japan, I was involved in a pretty significant incident of cross-cultural miscommunication. After watching visiting the Tokyo Edo Museum and watching Sumo, all the NanoJapan students, a few KIP students, and Kono-sensei and Packard-sensei went to Asakusa for dinner. More than 20 of us arrived at the very small restaurant, where there was a very long table set up for us. We filled in the table from right to left. A few other NanoJapan and KIP students and I were at the end of the line, so we got the left-most seats. In front of our table, there was another family having dinner. There were presents on the table and in a large trunk on the floor beside their table, so we assumed they were celebrating a special occasion. As we were in the process of filling in the left-most seats on the table, we heard a large crash. The five of us in the vicinity looked down and saw that a bag had fell to the floor from a chair it was sitting on. At first, we didn’t think it was a big deal, until we saw wine pour out of the bag and all over the floor. The restaurant staff rushed over to clean up the mess, and the five of us just looked at each other not knowing what to do. Two of the five students in the vicinity could speak Japanese, but no one really did anything for a few minutes. After we all realized what had just happened, one of the Japanese-speaking students asked someone from the table how much the bottle of wine was. He replied ¥11000 in Japanese. I was surprised not only because of the cost of the wine, but also because it had just fallen to the floor.

After finding out the cost of the bottle of wine, we still weren’t sure what to do, so we sat down at our seats. By this time, Packard-sensei and Kono-sensei had taken notice to the incident, but did not confront the other table. I sat down thinking that someone either from the restaurant or from the other table would approach us about the situation. However, the other table never came to us, and initially spoke exclusively to the restaurant staff. While we were waiting to order, we talked about what to do next. A few of us wanted to apologize, another offered to pay for the bottle, but we were told not to approach the other table by another student. We weren’t sure who knocked the bottle down, or if anyone in the group even caused it to fall to the floor. The bottle was sitting upright on a chair cushion, so any little bump would have caused it to topple over. Because of this, we thought that by apologizing we would be admitting guilt. This is usually the case in America, so we refrained from doing so because we weren’t sure who or what had caused the incident. Moreover, it was brought to our attention that since such an expensive bottle of wine was placed in such a poor location, if we did indeed accidentally bump the chair, it wasn’t entirely our fault. Finally, another student also said that even if the other table was sure that we caused the incident, they thought we should see a receipt for the bottle of wine before we gave them ¥11000. Because of this, the five of us chose not to do anything, and wait for a request to explain what we thought happened either from the restaurant staff or from the other table.

After a significant amount of time passed, the other table was getting visibly angry, but we still didn’t act. Some more time went by, and we saw that the police had arrived. Packard-sensei, Kono-sensei, some members from the other table, a member from the restaurant staff, and the police exited the dining area and went to talk outside for a while. The rest of us stayed where we were and talked about what we should do next. However, since some of us couldn’t speak Japanese, and the members from the other table couldn’t speak English, it was very difficult to communicate.

It turns out that the family was celebrating someone’s birthday during that dinner. The bottle of wine was a gift. However, the broken gift wasn’t the cause of the other table’s anger; it was the fact that no one from our table approached their table to either apologize or explain what they thought happened. To them, it seemed like we didn’t care they we had just ruined their evening. In addition, they were angry that we acted surprised about the cost of the bottle of wine, as if we thought they were being dishonest to take advantage of the incident. To make matters worse, the family had traveled from somewhere far away from Tokyo to celebrate the person’s 60th birthday. In Japanese culture, the 60th birthday celebration, or Kanreki, is special because it signifies that that individual has been through the Chinese zodiac 5 times. At the time, we weren’t aware that we had probably ruined a very special celebration. The other family, however, just wanted us to acknowledge that something had happened, and that we were sorry that such an incident occurred. From our point of view, however, we thought that even acknowledging that something had happened was an admission of guilt. Additionally, the language barrier made it very hard for us to communicate with them easily.

From my experience living in the United States, if person A believes that person B caused something, person A will be quick to confront person B. Person B then either can refute or acknowledge that they caused the thing. In this case, I was expecting this from either a member of the restaurant or from the other family. However, this didn’t happen. From my point of view, it seemed that the other table was waiting for an admission of guilt, which I wasn’t ready to give, as well as a payment of ¥11000. From the other table’s point of view, our group was disrespectful and inconsiderate because we didn’t approach them about the incident first. From my point of view, approaching them to say that I didn’t know who or what caused the bottle of wine to fall to the ground—what I thought was essentially directing the blame to them—so soon after it happened would only make them more angry. Additionally, not being able to tell them in Japanese also made it difficult. From their point of view, our lack of approaching them only caused them to become more angry. Finally, from my point of view, the cost of the bottle of wine as well as the incident itself was surprising. From their point of view, our surprised attitude conveyed that we thought they were lying about the wine bottle’s worth. These misunderstandings caused the incident to become a big deal, and ruined both our night as well as the night of the other family. Thankfully, however, Packard-sensei and Kono-sensei were present to resolve the incident.

From this experience, I learned pretty quickly that I can’t always apply how I’ve been brought up to act to situations involving other people, whether Japanese or American. I understand that the way I reacted—despite having good intentions both for our party and for the other family—only caused the situation to get worse. I also think, however, that such cultural misunderstandings should be learning experiences for both groups—I learned a lot about expressing empathy towards others, and I think the family from the other table learned that our intentions were good at heart, despite how he demonstrated them. It just so happened that my first cultural misunderstanding had to coincide with two large group gatherings, an expensive bottle of wine, and a very special occasion.

I think differences in the way people deal with difficult situations are not strictly Japanese, American, or any other culture. They reflect how the individuals are brought up and their past experiences, and it’s impossible to glean such information from the country they currently live in. I think the only way effective way to understand the concerns of the other party is to critically assess how they are acting at the time and how to most painlessly resolve the situation for both parties, regardless if those concerns conflict with my first instincts.

If I were to encounter a similar situation, I still would not confront the other party immediately. I would not quickly admit guilt, nor would I go ahead and pay for the damages. I would, however, more consciously assess how the situation was progressing and act in such a way that would most fairly resolve the conflict. More specifically, in retrospect, the facts that they, or the restaurant, hadn’t approached us about the incident after a few minutes should have been a sign that we should go speak to them first. Knowing what I know now, in this situation, I would have approached the other family and (with the help of a translator) apologized that such a special night was ruined. I would have then asked them if there was anything I could do to help resolve the situation. In this case, because what happened was so ambiguous, I was too caught up with protecting myself and the others in our group that I neglected the concerns of the other party. In doing so, I contributed to making what could have been a minor incident into a major problem that negatively affected both parties.

Welcome party!: My lab mates threw me a welcome party this week. Apparently, Dominos pizza in Japan is very expensive. The toppings are very unique, though.

Shibuya crossing: So many people; all these people crossed the street in the span of 20 seconds.

Odaiba: Went to visit Odaiba this weekend. The most futuristic city I’ve seen!

Research Update

After speaking to many of my lab mates, it seems that my research plans from my previous report were too broad. I was told that successfully working on both carbon nanotube growth and their applications for solar cells would be enough to constitute a PhD thesis, and that it was probably unfeasible to complete any meaningful work during my short stay if I worked on so many topics at once. Instead, a few students suggested that I spend my time working specifically on one area the lab has not yet explored. I spoke briefly with my mentor, Maruyama-sensei, and a few other members at my welcome party and they suggested that I spend the first few weeks observing the entire solar cell process, from CNT synthesis, to CNT characterization, to CNT self-assembly to a micro-honeycomb network, to solar cell fabrication. After understanding and getting to experience all steps in the process, I should then decide what part I find most interesting, and focus on that. Up until now, I have worked on CNT synthesis and characterization, and this week, I will be observing one of my mentors work on SWNT self-assembly and solar cell fabrication.

For now, however, I am most interested in using Cu for diameter control of SWNT growth. Thus, as a revision to last week’s update, I will spend the rest of this week observing while also working to obtain repeatable CVD results. I’ve created a rough timeline of the things that I will try to accomplish each week:

Week 1: Learn fundamentals behind CVD, SWNT characterization, projects and previous work happening in the lab; observe mentor preforming CVD, Raman, SEM

Week 2: Preform CVD, Raman, SEM independently

Week 3: Preform CVD (Co/Mo), Raman, SEM independently, try to get repeatable results; watch Kehang fabricate solar cells from SWNTs synthesized from Co/Mo; decide focus for project (Assuming I continue with CNT growth)

Week 4: Preliminary CVD with Co/Cu, observe how tubes differ from Co/Mo preparation

Week 5: Change synthesis parameters, characterize nanotubes

Week 6: Change synthesis parameters, characterize nanotubes

Week 7: Change synthesis parameters, characterize nanotubes

Week 8: Change synthesis parameters, characterize nanotubes

As I progress through my research internship, I will continue to make revisions. For now, however, I am limiting the scope of my project to SWNT synthesis, and attempting to synthesize small-diameter, high-quality nanotubes with the use of Co/Cu.

This past week, I completed my first few CVD experiments synthesizing VA SWNTs with Co/Mo at 800 ˚C. After CVD, I characterized the samples with Raman spectroscopy and SEM. Raman spectra and SEM images of the carbon nanotubes I synthesized are shown below. However, the results I obtained were not the best despite my mentor watching me preform each step. My mentor also said that he has not been able to get good CVD results in the past few weeks. At first, we thought it was because the lab recently started using a new Si substrate for CNT growth, but today (Monday, 6/23), we found that the quartz tube used for CVD was broken. Since the tube is usually mounted to a pump, no one noticed. We had an old quartz tube that we set up with the CVD, and tomorrow we will try using it for experiments. Hopefully, everything will go smoothly and I will be able to get better CNT growth. If not, I’m not sure what we will do, but we will surely discuss this problem during group meeting on Wednesday.

Perhaps the most prominent difference between my experience with working in labs in the US and in Japan is the prominence of hierarchy in my lab in Japan. The easiest way to recognize this is through the use of honorific speech. I have noticed that all members of the lab will refer to the professor as sensei, regardless of how close they are personally. This is very different to my lab back at Rice, as all members of our lab refer to our professor by his first name. Additionally, in my lab in Japan, to speak to the sensei, one usually needs to make an appointment beforehand. On the other hand, back at Rice, students usually simply knock on the professor’s door if they have a question or would like to meet briefly.

I was quickly introduced to the hierarchy-rules of my lab during my first group meeting. For background, lab meetings between my lab back at Rice and my lab at the University of Tokyo are very different. At Rice, for each lab meeting, we would usually schedule one member to present each week. The presentation would usually consist of a detailed explanation of what that student had completed in the past couple of months, and would then be followed by discussion between the professor and other students. Group meetings would usually last approximately an hour and a half. Conversely, however, my group meetings in Japan consist of each member giving a brief 5-10 minute presentation about what they had accomplished in the one week before each meeting. Since every member presented, the lab meeting was approximately 4 hours long. However, what I didn’t know was that each member presented in order from youngest to oldest. As such, seating was arranged in which the bachelor students would sit on one side of the table while the sensei’s would sit on the other side (the table was U-shaped). For my first lab meeting, I was unaware of this, and it became a very awkward moment when I sat down on the side the sensei’s were supposed to sit. I ended up sitting in between Maruyama-sensei and another assistant professor. Since there is usually much discussion between the sensei’s at the end of each student’s presentation, I felt like I was in the way with Maruyama-sensei and the other assistant professor talking around me the whole meeting.

This situation quickly demonstrated to me the many unspoken rules in our lab that are usually founded upon the hierarchy between members. While I did expect a large degree of hierarchy in the workplace—from the exercises in the pre-departure program, as well as some of the cultural lectures during the orientation program—I did expect them to be much more direct and noticeable.

Another a few other differences between my lab in the US and my lab in Japan are the working hours and the necessity of breaks. Back at home, most of the students were in the lab the standard 9 AM-5 PM workday, and usually only took lunch as a break. In my lab in Japan, however, most of the students come into lab late, from between 11 AM to noon, and leave late, after 8 or 9 PM. While they are at work longer, from what I’ve noticed, the students take many more breaks, from sleeping at their tables, to surfing the Internet, to going to the gym to work out. While students work longer, I think the US type of work schedule produces much higher quality work, as students are more usually more focused and motivated.

Finally, a third difference I’ve noticed are the different styles of assistance students provide others. In any lab setting, when I am not sure how to use an instrument, I usually ask the person nearest to me for help. Usually, they know the answer, but sometimes they might not because they are working in a different part of the lab or on a different project. In my lab back home, if the student doesn’t know the answer, generally, they will usually politely direct me to someone who knows the answer. However, in Japan, the few times a student I asked for help didn’t know a quick answer, they would take time out of their work to figure it out with me. For example, today I didn’t know how to operate the vacuum pump to purge the chemical storage container so I asked a student nearby who was in the middle of doing SEM. He was also relatively new to the lab, and wasn’t sure how to do it either. Instead of directing me to a senior lab member who could quickly walk me through the process, we spent the next half an hour figuring out how to do it ourselves. Similar situations have occurred, and while I insisted each time that I could save them the time by asking another student, each time the student I was asking insisted to help me themselves. I think this largely stems from the sense of team our lab values. I have often seen students do experiments in teams of two of three—something that I seldom see back at home.

While it seems that my lab strongly values a sense of team, I do think that both Maruyama-sensei and the students value results more than they value hard work, which is different to my lab at Rice. In my opinion, at Rice, my advisor largely values how hard his students work, rather than the type of results they produce. For example, last semester I began an individual project, but didn’t advance too far by the end of the semester due to a variety of problems that could have been avoided. However, he seemed to really value the effort and time I put into the project. On the other hand, from what I have observed at group meetings, Maruyama-sensei really values the results his students present, regardless of how long it took them to get those results. I think this is also reflected in the flexible work hours in Japan—from what I have observed, students can come into lab as long or as short as they like, as long as they produce results. My advisor back at Rice, however, specifically states that he prefers students be in lab at least 8 hours a day. Having experienced both attitudes towards work, I prefer the more lenient working hours in Japan. However, I also like that my work is still heavily acknowledged in the US whether or not I produce results.

Toshogu Shrine, Nikko: This weekend, I took a 2-day trip to Nikko. It’s approximately two hours away from Tokyo by train, and I stayed overnight at a Ryokan. I visited the three large shrines—Toshogu Shrine, Futarasan Shrine, and Rinno-ji Shrine.

Kegon Falls, Nikko: Nikko National Park is also in the area. This is Kegon Falls after taking an elevator 100 meters down to its base.

Chuzenji Lake, Nikko: Chuzenji Lake is right next to Kegon Falls and has a great view of the water and mountains. The water there was so blue!

Research Project Update

This week, I started my research project. Today—6/30/2014—I prepared four different VA SWNT samples with Co/Mo as the metal catalyst. Originally, I had planned to carry out the CVD at 4 different temperatures: 650, 700, 750, and 800 ˚C. However, after completing visually inspecting the SWNTs prepared at 750 ˚C, I decided not to try and grow SWNTs at lower temperatures. My mentor said that he had once tried to grow nanotubes all the way down to 600 ˚C, but that there was little difference in the nanotubes grown below 750 ˚C. Instead, I used the two remaining dip-coated substrates I prepared in the morning to repeat CVD at 800 ˚C. However, this time, I changed the growth times, from 5 minutes to 1 minute and 2 minutes. Tomorrow, I will characterize all four samples with Raman and SEM. Additionally, tomorrow, I will prepare grow four more samples of SWNTs with a Co/Cu metal catalyst. I will grow the nanotubes at four different temperatures—600, 650, 700, 750 ˚C—under the same conditions I grew nanotubes at today.

As of now, I have no further data. However, I think that my research project is now much more clearly defined than it was last week. I will be looking at various growth conditions to alter the diameter of SWNTs synthesized with either Co/Mo or Co/Cu metal catalysts. My goal for this project is to obtain small diameter (sub-nanometer) VA SWNTs by synthesis with the Co/Cu catalyst.

This week, at the Mid-Program Meeting in Okinawa, we discussed some of our biggest accomplishments to this point in the program. Some discussed research-related accomplishments and others discussed language and culture-related accomplishments. I think my biggest personal accomplishment has been adjusting to many of the cultural differences without necessarily being told all of them. My understanding of these differences have come from some misunderstandings, such as the wine bottle incident, some mistakes, such as my first group meeting, and through simple observation during daily interaction with the Japanese. Many seemingly insignificant things, such as learning to put money in the little trays in front of the registers, separating trash down to the last napkin, and pushing your umbrella to the other side when walking past someone on a rainy day, have all culminated in this being my greatest success thus far.

That being said, I still think one of my biggest challenges is getting past the language barrier. At times, it can still be very difficult—and even frustrating—to communicate with my Japanese counterparts. For example, last week I had a question about one of the instruments in our lab. There was another Japanese student in the basement at the time, so I decided I would just ask him how to resolve my problem. We ended up having a very uncomfortable moment when neither of us could understand what the other was saying. Additionally, when I said I could go upstairs quickly to ask my mentor what to do, he insisted on helping me himself. However, he didn’t understand my question, so it was difficult for him to help me. I think it’s instances like these that demonstrate cultural differences and how the language barrier can make them exponentially worse. In my case, it would have been more efficient to simply go upstairs and find my mentor. In the other Japanese student’s case, I think his team mentality made him feel compelled to assist me in any way that he could. This, coupled with the fact that we couldn’t understand each other because of the simple language barrier made everything much more difficult. I wasn’t very sure how I should have handled this situation. I couldn’t have stopped him from helping me—if I had insisted on going to my mentor, it would have seemed like I didn’t value his attempt to help—, but him trying to help me also wasn’t getting either of us anywhere—he was clearly busy with his own experiments, and him continuing to attempt to help made me feel even worse as I was taking more and more of his time. Eventually, another Japanese student walked in to the basement, and was able to help clear up the language barrier and resolve my problem.

Currently, I am making good progress with my research project. I am following the timeline defined by the abstract I sent my US coadvisor a couple of weeks ago, and the results I have obtained are promising. This week and next week I will continue to complete the experiments I have planned in preparation for my poster. I think the biggest benefit I got from the Mid-Program Meeting was the debrief session we had with all the NanoJapan students. It was great hearing many of the stories that the other students had to share, and it allowed me to gauge how I was progressing with my Japanese language and research project with respect to the other students. I think the biggest take away from the Mid-Program Meeting was the critical incident analysis session and the discussion with other students about how they dealt with problems in their lab. I was cool to see how other students approached problems that were similar to those that I had or am currently dealing with. I will undoubtedly use many of their suggestions during the remainder of the summer.

Airport : Getting to the airport by myself for the first time! I’m surprised I didn’t miss the flight.

Failed group hair flip in water photo: We all tried to do a group hair flip in the water, but as you can see, we were not synchronized.

OIST Campus: The very beautiful OIST campus. I wonder if you ever get tired of the view?

Research Project Update

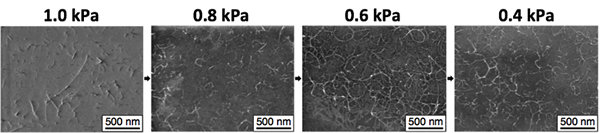

This past week I have been in Okinawa for the Mid-Program Meeting and visit to OIST. However, before leaving last Thursday, I was able to complete all 8 CVD experiments I planned for diameter-controlled growth of SWNTs. I also finished characterizing all samples by Raman at four wavelengths and SEM. The Raman data is attached in a separate .pptx, but the general trend shows that at lower temperatures for the Co/Cu bimetallic catalyst, the SWNT diameter decreases. This is also the case for the Co/Mo catalyst, but occurs to a lesser extent. This is demonstrated by the RBM peaks in the 100-200 cm-1range—characteristic of larger diameter nanotubes—and the 200-300 cm-1 range—characteristic of larger diameter nanotubes. For the Co/Mo samples, peaks populate both ranges at high temperature, and then shift to the 200-300 cm-1 range at lower temperature. However, significant peaks in the lower range can still be found at low temperature. The Co/Cu samples demonstrate the same behavior, but the peaks in the lower range start to disappear below 800 ˚C. At very low temperatures, only peaks in the higher range are observed.

SEM data demonstrates that at high temperature (800 ˚C), both the Co/Mo and Co/Cu samples grow well-packed vertically-aligned SWNTs approximately 20 µm in length. However, for both samples, as temperature decreases, SWNTs grow to shorter lengths and are less well-packed.

This week, I will continue my experiments growing SWNTs by varying the growth pressure. I have not yet decided what pressures to try, but I will discuss with my mentors soon. I will also continue to characterize with the same methods. In addition to growth, this week we will also use some of the SWNTs I grew with Co/Cu and Co/Mo last week for solar cell experiments. I am still in the process of learning how to prepare solar cells. By the end of this week, I will also decide what third growth condition to vary.

After living in Japan for almost three months now, I have come to understand that one of the best ways to truly learn a second language is to live in that country for an extended amount of time. I don’t think I could have learned nearly as much Japanese as I did during the first three weeks without living in the country. By the end of language classes, I still could not hold a conversation in Japanese, but I could definitely survive. I could purchase things from stores and kombinis, and ask for directions from people on the street and in subway stations.

In my Japanese labs, however, it was much harder to use my Japanese. In addition to the fact that many of my lab mates knew English and wanted to practice speaking it to me, there are many more technical words that I needed to use on a daily basis, but had not learned in language classes. At times, however, there have been some issues with the language barrier. Perhaps the most difficult miscommunications occur when I ask other Japanese students for help in the lab, but they do not understand what I am saying. After I ask the question and find out that they can’t really understand what I am saying in English, and I can’t understand what they are saying in Japanese, it’s sometimes difficult to know when to back out of the question.

Additionally, there have been some instances when I have been in public and it has been hard to communicate with others. This weekend, for example, I visited the Tohoku region and visited the Chuson-ji temple in Iwate Prefecture. When entering the temple, I accidentally went in through the exit, so I didn’t know that I had to buy a ticket. After I got about half-way in, the lady at the ticketing booth ran in after me and started talking to me in Japanese, but I didn’t understand what she was saying except for the word ‘ticket’. She also didn’t understand what I was saying, so there were a few minutes of uncomfortable standing around when I didn’t know what she wanted me to do. Eventually, she walked me out of the exit where I entered and around to the entrance where there was a sign that had ‘800円’ written on it.

While I haven’t taken any classes at Todai to continue my Japanese language instruction, I have been working independently on the Japanese for Busy People book we used during the first three weeks. I have been progressing much slower than I did during the first three weeks, but this method allows me to fit in Japanese language training to my busy lab schedule. Outside of lab, I try to use the words and phrases I learn from the book. I probably use them incorrectly the first few times I try, but the recipients usually smile a little and politely correct me. After I get back to Rice, I would like to continue learning the Japanese language. Hopefully, I can score well on the oral proficiency exam with AJALT and test into JAPA 201, Intermediate Japanese Language and Culture I. If not, I would also be fine with taking Introduction to Japanese Language and Culture I.

For the rest of the summer, I will continue my Japanese study as I have been, and continue to work hard on my research project. I have also started my 21-day rail pass, and will be traveling the country on the weekends. This past weekend I visited the Tohoku region, and next weekend I will be visiting the Kansai region. The weekend after that, I will be visiting Packard-sensei’s house south of Tokyo.

Shinkansen: Riding the Shinkansen for the first time was a cool experience. It was so quiet, so convenient, and so fast!

Gyutan for lunch: Tried Gyutan for lunch for the first time at Matsushima Bay with Vernon. It had a very interesting, tough texture, but was so good!

Motsu-ji Temple: Visiting the Motsu-ji Temple in Hiraizumi. It was interesting to walk around the whole area of Hiraizumi, where I saw the Motsu-ji Temple, Chuson-ji Temple, and Geibikei Gorge!

Research Project Update

This past week, I completed CVD growth with varying partial pressures of EtOH. Instead of changing to total pressure of EtOH during growth, Kehang and I decided that varying the partial pressure of EtOH by increasing the flow rate of Ar while keeping a constant EtOH flow rate of 50 sccm would be easier and yield more consistent results. Thus, I completed 6 experiments with flow rates of 50 and 400 sccm of Ar at 600, 650, and 700 ˚C. From previous experiments, I also had data with 0 sccm Ar flow.

The Raman spectra at 488 nm were promising. Above 650 ˚C, we observed very distinct and broad Breit-Wigner-Fano line shifts near the G-bands, characteristic of small diameter SWNTs. Tomorrow, I will complete 5-laser Raman on the same samples to further confirm our results. Next week, I also plan to complete my last set of CVD growth experiments by varying the ratios of Co/Cu to determine if one ratio favors small diameter nanotubes.

Currently, I have no more data to present (the data for the 488 nm Raman still needs to be processed), but I will have completed Raman characterization on my second set of experiments very soon. By the end of this week, I also hope to complete my third set of CVD growth experiments, and by the first half of next week, I hope to have those samples characterized.

During the second half of this week, I will also begin preparing my poster. I will have data from my first two sets of CVD experiments, and I will add the data from the third set of CVD experiments at the end of next week before the June 27th deadline.

Initially scrutinized as a “Rikejo”—a woman in science and technology—Dr. Haruko Obokata was recently found guilty of falsifying data in her work on groundbreaking stem cell research. The entire controversy occurred over a course of a couple of months. Most recently, RIKEN announced that it would not reinvestigate the study in question because Obokata intentionally committed research misconduct.