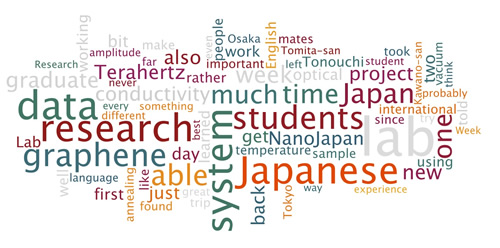

Nicole Moody - NanoJapan 2014

Rice University

Major: Physical & Theoretical Chemistry

Class Standing: Sophomore

Anticipated Graduation: May 2016

NanoJapan Research Lab: Tonouchi Lab, Prof. Masayoshi Tonouchi, Osaka University

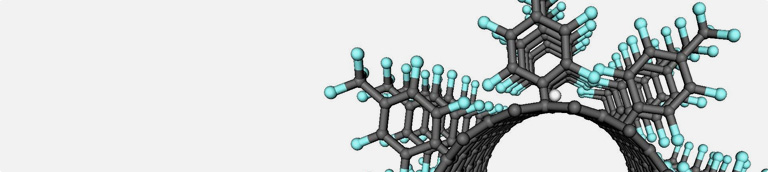

NanoJapan Research Project: ![]() >> Poster Presentation Award Winner

>> Poster Presentation Award Winner

Why NanoJapan?

The NanoJapan Program aligns perfectly with both my research interests and my interests in international graduate programs. It will expose me to cutting-edge research and a completely different culture, allowing me to use leading techniques at a top university, but also to open a door to future collaborations that would otherwise have to stay shut due to linguistic and cultural barriers.

For physics and engineering students nationwide, the NanoJapan Program is an opportunity to experience new perspectives and new approaches to problem-solving, and to make a connection in a country that’s a superpower in science and technology. I’m looking forward to learning new laboratory techniques and a new language, working with new equipment, experiencing a new culture, and (hopefully) discovering a new favorite food.

My goals for this summer are to:

My favorite experience in Japan was… presenting my research project alongside Kawano-san at the Tokyo symposium and celebrating a job well done afterwards in Shinjuku.

Before I left for Japan I wish I had… watched more anime or classic Japanese movies so I could have had more to discuss at first with my lab mates.

While I was in Japan I wish I had… tried more foods. I usually stuck to the same few dished every day for lunch and dinner; I wish I had been more culinarily adventurous.

Having completed the NanoJapan program, I am now more confident in my abilities to participate in international collaborations. I’ve developed valuable research and intercultural communication skills, and I’ve formed an incredible network of colleagues and friends. NanoJapan has cemented my desire to continue to pursue research in graduate school, and thanks to the lessons I’ve learned, I’ll be prepared to be a valuable member of an international research lab.

In all honesty, I had no idea what to expect when coming to Japan. I thought it might be something like the future predicted by someone from the early 1950s: lots of bright colors, incredible appliances that make daily tasks a breeze, and revolutionary transportation (although instead of flying cars, people would instead be taking the magical cat bus from My Neighbor Totoro everywhere). I wasn’t entirely incorrect. Places like Akihabara and Shibuya have the bright lights I expected, and we did stumble across some vacuum robots that were able to recharge themselves and said, “Sumimasen!” when they bumped into something, but I expected to feel completely different in Japan. There’s no magical cat bus or flying cars, no ground-breaking technology (aside from all of the exciting things I’ll talk about in the research section); it’s just another place to learn and explore.

I was surprised that convenience store employees speak rapid-fire Japanese at me every day when I go to buy o-bento or onigiri, but I’ve come to get the gist of what they’re saying, and I know how to pay and ask for a bag and chopsticks. The food was different and exciting at first, but my body has had some difficulty adjusting to it, so I’ve decided to put adventurous eating on hold for the time being and stick with what I know won’t make me sick. I thought that fish would be eaten at almost every meal, but fried pork is much more prevalent and popular.

My language classes have been very challenging. They’re so fast-paced that there’s never any time for review, so I feel like I’m forgetting a lot of what we learn. I’ve been trying to focus on pronunciation of words. I thought that the hiragana and katakana would reveal the definitive pronunciation, but words are often contracted and some syllables dropped. Because of this, my strategy has been to write down the phonetic pronunciation of new vocabulary using a mix of Romanized letters and phonetic symbols rather than writing words in hiragana and katakana. I’m starting to notice some pronunciation patterns, but until I grow more comfortable, I’ll be sticking with my personalized phonetic alphabet.

I’ve been very surprised by how quickly I’ve bonded with not only my fellow NanoJapanners, but with the KIP students as well. It’s been nice to interact with Japanese students my own age and learn about their hobbies and unique perspectives. After our first discussion, all of us went to an Indian restaurant for dinner. I sat next to a student who had been saving money for three years for a three-week trip to America. He was so excited to share his knowledge of American customs (his mother had told him to never stick his hand inside his jacket, because Americans will think you’re hiding a gun) and to learn more. I told him about In-N-Out Burger, the Grand Canyon, and rodeos, and tried to convince him to come to Texas; perhaps he’ll pay a visit to Houston in September.

I’ve been trying my best to not do anything wrong from a cultural standpoint. It seems that I’ve been adapting rather well, but that could be because I’m completely blind to my incorrect actions. The one mistake I’ve willing and openly made so far has been eating while walking in public. I had just bought some fresh bread from Mount Thabor, and I was so hungry that I could resist taking a few bites of it on my way back. I didn’t get any death glares from the people I passed by, but I’ve never actually seen anyone eat in public. I suppose my question for the week is how big of a mistake did I make? Is it extremely rude to eat in public, or is it just something people don’t usually do?

It’s been an action-packed few days so far, and I’ve had some amazing experiences. Here are a few photos of some of my adventures.

Hello Tokyo!: A few of us took a trip to the top of the Tokyo Tower. I decided to take a picture of the view with the Hello Kitty plush I bought for my little sister, so she’d know I was thinking of her in Japan. I’ve been keeping in contact with my family, and they’ve been excited to hear about all of my experiences so far.

NanoJapan and KIP Take Asakusa: Skylar, Jade, Ben, and I had some great bonding experiences with some of the KIP students during our trip to Asakusa. We were able to explore more restaurants thanks to them, because we didn’t need to rely on picture menus. We ended up having boiled beef intestines with scallions and tofu, and it was DELICIOUS!

Reflections in Kamakura: The last trip of the first week was a trip to Kamakura. I was initially concerned about my decision to go, because I was very tired and a bit behind on my report. :/ However, the trip ended up being exactly what I needed: a quiet trip outside the city to relax, enjoy the beauty of nature, and reflect on my incredible first week in Japan!

Intro to Nanoscience Lectures: Kono-sensei’s Intro to Nanoscience lectures provided a breakdown of the differences between classical and quantum theories of electrical conduction. As a bit of background, the lecture went over the classical Drude Model before delving into some basic principles of wave mechanics, such as de Broglie wavelengths and Schrödinger’s equation. The lecture introduced the classification of metals, semiconductors, and insulators in terms of changes in resistance with increasing temperature before delving into the concept of band gaps in insulators and semiconductors and the corresponding optical adsorption processes. Kono-sensei explained the transition of bonds to bands in solids versus molecules, as well as the existence of quantum wells, wires, and dots. We briefly discussed the miniaturization of technology, and how soon devices will be delving into the quantum rather than the classical regime.

We talked about the band structure of a current common semiconductor, silicon, and how its indirect band gap causes it to be a poor emitter, and how other semiconductor heterostructures can not only be lattice-matched, but also be manipulated to possess various types of quantum confinement. Finally, we discussed some of the applications of nanoscale semiconductors as well as briefly touching on the band structure of some of the materials we’ll be studying this summer.

I’ve never taken a solid-state physics class, although I was briefly introduced to the concepts of band gaps in inorganic chemistry, so I found the explanations of solid-state physics in the lecture to be particularly interesting and very helpful. I was also happy to encounter some concepts a bit closer to home when I saw the slide about the surface plasmons of gold nanoparticles.

Overview of Research Project at the Tonouchi Lab, Prof. Masayoshi Tonouchi, Osaka University

The material I’ll be studying this summer is graphene, a two-dimensional array of carbon atoms with many interesting properties and potential applications. Graphene is a zero band gap semiconductor with many intriguing properties, including a high electron mobility at room temperature, a high mechanical strength, and zero effective mass of electrons. For my project, I’ll specifically be investigating the effects of various substrates on the electron mobility of graphene using Terahertz time-domain spectroscopy. The relationship between the substrate used and the Terahertz transmission and optical conductivity of graphene is important to understand, because graphene has a potential application for integration in high-frequency Terahertz devices (Allred et al. 2013).

If I’m riding the Houston MetroRail, I must be truly desperate. Based on my experiences and those of my friends, it’s not convenient; it’s uncomfortable, and sometimes even dangerous. Every time I’ve ridden it, I’ve been asked for money, despite my attempts to dress down to look less conspicuous and to not make eye contact with anyone. From my fellow Rice students, I’ve heard stories of people from the MetroRail following students into restaurants and even back towards their dorms until the students pay them. I try to avoid taking the MetroRail as much as possible. Tokyo public transportation was a pleasant surprise.

There are a few “rules” that people follow when using public transportation. On escalators in subway stations, people wishing to walk up or down the escalator do so on the right, while people who wish to simply ride the escalator hang to the left. During busier hours, this formation stays intact, but the walkers pick up their pace considerably, and the riders try to accommodate them as much as possible by scooting over. When it comes to the stairs, while there are markings to indicate which side people should stick to when ascending or descending, it’s usually just a free-for-all. Since fewer people use the stairs, anything goes; ironic considering it’s the stairs and not the subway that have clearly labeled instructions for use.

There might be an elaborate formula that can be used to determine whether or not it’s okay to take an empty seat on the subway that takes into account the age and physical capabilities of the passenger as well as the fullness of the train and duration of the trip, but I haven’t figured it out yet. It just seems that if you’re in the right place at the right time, and there happens to be a seat available, take it. I haven’t observed any instance in which someone gave up their seat for someone else, and there certainly hasn’t been any competition for empty seats. If a seat is open, sit down; if not, stand and try to stay out of everyone else’s way.

Most travelers stare down at their smartphones during the entire duration of their trip. Some take naps (I still haven’t figured out how they wake up in time for their stop), and others read books or manga. The rarest activity on public transportation seems to be talking to fellow passengers. As many times as I’ve ridden the subway, I’ve only observed one or perhaps two conversations taking place between passengers in very hushed tones. I sometimes worry that our group is being too loud when we talk to each other on the way to some adventure.

One thing that people certainly do not do is strike up conversations with strangers. Everyone seems to keep to themselves during their commutes, and this seems to be the most important norm for politeness and appropriateness. The first time we rode the subway, a girl noticed how we were struggling and helped us get Pasmo cards, but other than that, we haven’t had anyone talk to us in the station or on the train. I’m used to the Southern openness of people asking me “where I’m headed” when I take the bus, or the Southern hospitality of giving directions when people seem the least bit lost. People will give you directions if you ask them, but unless you’re turning in circles, they won’t initiate giving help.

I probably prefer this practice over being bothered on the Houston MetroRail all the time, since I’m a bit of an introvert, but it can seem very isolating. There couldn’t be some romantic comedy plot that starts with a chance meeting on the subway; the couple meets and and hits it off, and ends up missing their respective stops because they can’t stop talking to each other. The subway is a means of getting from Point A to Point B, not an opportunity to meet others. Compared to that of the U.S., Japanese public transportation is more convenient in almost every aspect. It’s timely, no one bothers you, and you can take it just about anywhere. But at the same time, strangers won’t ask you how you’re feeling or recommend activities once they find out your destination, and I miss that aspect of Southern U.S. transportation.

Another difference between the public transportation of the U.S. and Japan is the passengers themselves. Everyone I’ve seen on Japanese public transportation has been very well dressed (come to think of it, everyone I’ve seen in public in Japan has been very well dressed) in stark contrast to the American practice of choosing comfort over style during commutes. As I mentioned previously, I choose to wear my less nice clothes on the Metro to avoid drawing attention to myself, but if I wore my “bus pants” on the Japanese subway, I’d stand out considerably.

While it could be argued that the Japanese practice of not engaging in conversation with random people is a practical difference (people don’t want to be bothered on the subway, so they don’t bother others), dressing up, even for long weekend trips, is a cultural one. There are different standards of typical appropriate dress in the U.S. and Japan, Japan’s being significantly more formal. I try to fit in with Japanese subway culture, but I think I’ll let my inner American shine through, and choose sneakers over heels when I’m riding the subway. Hopefully I won’t be the proverbial nail that gets hammered down.

The core Japanese value of wa or harmony is clearly evident on the subways. There’s never any pushing or shoving, there are no audible groans when someone claims an available seat before someone else; even during the busiest commuting times, everyone is very civil. If subway cars got as crowded in America as they did in Japan, it would be a recipe for disaster. I’d probably emerge form the experience with several bruises, and I’d probably be waiting a while to get on the train, since I’m not particularly pushy. It’s incredible that Japanese people can be so respectful of each other, even while on the run.

Week two was very hectic, since so much had to be done before the trip to Kyushu, but I did manage to visit the Pokémon Center in Daimon. It was nice to see a few familiar faces and purchase a few special souvenirs for my friends and myself.

Preparing for Kyushu: This photo was actually taken after the trip to Kyushu, and ironically, it contains a few items that I forgot during the trip, such as deodorant and my sister’s Hello Kitty plush. It’s supposed to signify all of the clutter I had to set in order before the trip. The battery represents the activity we prepared for the high school students, and the fan represents how horrendously hot it was this week!

Intro to Nanoscience Lectures: Professor Bird’s Intro to Nanoscience lectures provided a particularly helpful background of semiconductor bandgap engineering and the impact of graphene on nanoelectronics. In his bandgap engineering lecture, Professor Bird introduced the concept of heterostructures and their many uses before delving into the role of quantum states and bandstructures in bandgap engineering. We learned about the different band compositions of metals, insulators, and semiconductors and the presence and behavior of holes in the valence band of excited semiconductors. We then considered the effects of an electric field on the bands of semiconductors, touching briefly on the electric field generated by a pn junction. We then returned to the use of heterostructures in bandgap engineering, learning about different types of band alignment and the creation and manipulation of two-dimensional electron gases. Finally, we discussed the use of heterostructures in the creation of optoelectronics.

The graphene lecture was particularly interesting to me, because graphene will be my material of research this summer. It covered graphene preparation techniques, graphene’s incredible properties and distinct form of energy bands, and some of the challenges of and potential solutions for the creation of an efficient graphene transistor. I found the additional information about the band structure of graphene to be particularly helpful. After both Professor Kono’s and Professor Bird’s lectures, I think I’m finally getting a good grasp on the unique band structure of graphene, and the properties and challenges that come with it. I was particularly interested in the use of nanoribbons to overcome the lack of an energy gap in graphene.

The nanoscience guest lectures during week two were very technical, and at times a bit difficult to follow, but I tried my best to keep up. Professor Maruyama’s lecture covered different structures and synthesis techniques of carbon nanotubes. I found the portions of the lecture about chiral nanotubes to be particularly interesting, because my first research project was about chirality at the nanoscale. I also loved the SEM images of carbon nanotube “forests” and the simulation of the octopus growth technique of individual SWCNTs. Professor Ishizaka’s lecture covered a lot of ground, focusing on everything from angular-resolved photoemission spectroscopy to the Rashba Effect, but I found the last part of her lecture, her experience as a woman in science, to be the most interesting.

Professor Ishizaka was very optimistic about recent increases in the number of female professors, but she did mention that female researchers often have more limited research budgets, and foreign female students are very rare, and stand out a lot in science classes. Perhaps the most interesting comment was Professor Bird’s recollection that due to the economic decline in Japan in 1990, many Japanese companies announced that they wouldn’t hire any women. I was shocked that such a blatant act of sexism could have happened so recently, but Professor Ishizaka merely commented that this didn’t happen anymore, and moved on to the next question.

In our language classes, all of our Senseis asked us about our Kyushu trip, so we could practice using the past tense in Japanese. Since my study of Japanese only began three short weeks ago, my descriptions have been rather limited. “I saw Mount Aso, I ate a lot of delicious food, and I did a homestay. Kyushu was very beautiful and very enjoyable.” But it was so much more than the eighteen or so adjectives that we’ve learned so far, and I experienced and learned so much more than what I’ve learned to say so far in Japanese. While in Kyushu, I witnessed a rich mythology, a loving family, and an innumerable amount of bright children with equally bright futures in store. I was able to share a bond with others stronger than the language barrier, and I came back from the trip so happy that my cheeks were sore from smiling.

My experiences in Kyushu were so diverse and so memorable, that it would be virtually impossible to determine which had the greatest impact on me, but what I keep thinking about the most when I recall my trip is the scenery. Gone were the giant gray skyscrapers and bright lights of Tokyo. Instead, there were rows of green tea and mountains covered in trees. I was so happy to see nature again, free as far as the eye can see rather than confined to small gardens in the city. The air was crisp and clean (except near the sulfur deposits on Mount Aso), the sky was clear, and you could hear the sounds of nature.

I never expected that anywhere in Japan could be that naturally beautiful. Kamakura was calm and had some trees and rocks, but Kyushu had untamed nature in all its unadulterated glory. Even the more touristy attractions were engulfed by gorgeous scenery. The cave of Amaterasu was surrounded by a beautiful forest and had a clear natural stream running beside it. The Kagura theater was surrounded by old trees. The attractions didn’t try to overcome nature to accomplish something; they worked with it, thereby accomplishing beautiful results.

My host family, the Kais, exceeded my expectations in every way possible, and helped me debunk a few negative stereotypes about Japanese culture. We were told during culture class that a traditional Japanese woman is confined to the home, and is treated almost like the property of the husband of the household. For the Kais, this wasn’t the case in the slightest. In fact, the grandfather commented that the family relied on the strength of its women. The Kais were all very supportive of each other, and definitely reflected the Japanese value of harmony rather than the gender stratifications we learned about.

Maria Kai was a rambunctious middle school girl. We sang One Direction’s The Best Song Ever together at least three times, and she taught us how to hula dance. Ayumu Kai, also in middle school, slept through our first meeting with the family, but woke up for dinner. She was a bit more reserved than Maria, but still very sweet. Shin’ichi Kai and his wife were both strong and supportive parents. Mrs. Kai coached the volleyball team of her oldest daughter (who we were unable to meet because she was staying in her high school dorm), and Mr. Kai was the local Taiko drumming coach. The performance he scheduled was spectacular. The synchronization between he and the other drummers was perfection; it was obvious that he was an excellent teacher.

My favorite portion of the homestay was definitely dinner. The Kai family owned a local restaurant nearby, and prepared a feast for us of homemade soba noodles, fried asparagus and chicken, sashimi, ramen, and plum onigiri for dessert. It was the best meal I’ve ever had, and over the course of the dinner, I was able to learn more about their lives.

The language barrier was definitely an issue. I was very fortunate to have two excellent translators, Jade and Anni (KIP Japanese students), to help me, but it could be frustrating having to wait until the end of a conversation to find out what had happened rather than being able to jump in with them. Fortunately, I was able to say a few important things like my self-introduction, and that the food was delicious. I tried to rely on facial cues to provide clues about the content of the conversation, and I could pick out a few things here and there. I just tried to smile and nod at the appropriate times, and everything was fine.

I did make a few mistakes during the homestay. While eating dinner, I noticed that some of the family members turned their chopsticks around to grab food, then back around the other way to eat it. I tried to follow their lead, grabbing food with the square end and then turning the chopsticks around and eating with the narrow end, but with all of the delicious food, I got so excited to eat, that at one point I forgot to turn the chopsticks back the other way. Of course, the family noticed. I was panicked. Were they going to throw away the food I might have contaminated; ask me to leave? But everything was fine. The grandfather told me that as long as I didn’t eat with my hands, he didn’t mind.

From my homestay experience, I learned that culturally, there’s nothing to fear in Japan. Things might seem different on the outside; there might be tatami mats instead of hardwood floors, sliding doors instead of ones with nobs, but there are still loving families that laugh and eat together and drive their daughters to all of their activities in the family minivan. Kyushu has been the best experience I’ve had so far, and it’s energized me for the rest of the summer. As I move to Osaka this week, I’ll try to channel some of Maria’s and the Gokase kindergarteners’ abounding energy, maintain the excitement and determination for experimentation the Gokase high school students had during the science demonstration and competition, and of course, I’ll remember to turn my chopsticks.

Contrasting Gokase and Shiodome: I put these two photos together, because they reflect the contrast between nature in Kyushu and nature in Tokyo. On the left is a photo of Hama Rikyu, a Japanese landscape garden in Shiodome, while on the right is a photo I took on a random walk around the inn we stayed at in Kyushu. For me, the most interesting difference is that of scale. In the Shiodome photo, the buildings are much bigger than the trees, but in the Gokase photo, the opposite is true; the trees are dwarfing the house. This reflects the different balances of nature and development I observed in the two locations. Both places were beautiful, but the scenery seemed much more confined in Shiodome compared to the sprawling scenic landscapes of Gokase.

Orientation Program Overview

During the orientation program, I found all of the lectures and classes to be extremely helpful, but so were periods of “down time” that we could use to explore Tokyo with the KIP (Japanese) students. I learned how to navigate Japanese subway systems and about the life of a typical Japanese undergraduate student on my own terms and at my own pace by going out and exploring, and that was very helpful to me. In my language classes, the most helpful thing was the simulated conversations. Spoken Japanese will probably be the most helpful to me, so I appreciated any practice I could get. There were some classes that went over vocabulary words without using them in a conversational context. I often found these portions tedious and forgot the words I learned easily. My three Japanese learning strategies have been writing the phonetic pronunciation of new vocab words in roomanji, writing out conversational formulas with blanks to fill in with my own opinions and experiences, and trying to participate in class as much as possible.

The most important thing I’ve learned during the orientation program is that I have an incredible support network available during my time in Japan. I was so worried that I’d feel isolated and have to do everything myself in a very unfamiliar environment, but I know now that there are a plethora of people who can help me with any problems I might have.

Three burning questions I still have are:

Research Update

Professor Stanton’s Intro to Nanoscience Lectures seemed a bit more specific than the ones we’ve had in the past, focusing on semiconductor optics and femtosecond spectroscopy. We started with the basic concept of quantized energy levels and the particle/wave duality of electrons before delving into the electronic structure of direct vs. indirect band gap semiconductors, direct gap semiconductors being the optically active variety due to the Law of Conservation of Momentum. Professor Stanton then touched on the Effective Mass Theory, the existence of quantum wells, and molecular beam epitaxy, a technique used for the growth of semiconductor alloys. We learned about the photoelectric effect in metals, which are reflective, and thus don’t make good optical devices (although they work well for mirrors), as well as the photovoltaic effect in semiconductors.

Professor Stanton introduced three types of LEDs: conventional crystalline semiconductor LEDs, organic LEDs (OLEDs, aka the bendy ones), and polymer LEDs (PLEDs) before delving into the subject of photovoltaics and introducing different types of solar cells. We talked about the now-familiar p-n junction and the advantage of having a heterojunction over a homojunction to generate photons, but a new concept of using a p-n junction in solar cells to generate a reverse bias and absorb photons to create current was introduced. We concluded by discussing blackbody radiation and the many applications of semiconductors for LEDs, lasers, and solar cells.

During Professor Stanton’s femtosecond laser spectroscopy lecture, we learned about two types of lasers, continuous wave and pulse lasers, before being introduced to the concepts of Transport Theory and the quasiclassical equation of motion. Several scattering mechanisms in semiconductors were introduced, including phonons, defects, carrier-carrier interactions, and recombinations across the band gap. We then learned about the extremely small time scales required for faster and faster electronics, and the new physics and challenges such time scales introduce before delving into the concept of using pump-probe spectroscopy to reveal relaxation dynamics.

Coherent and incoherent dynamics were introduced as two components of semiconducting systems. Incoherent phonons have no phase relationship, while specific coherent phonon frequencies can be generated by adjusting the periods of a superlattice. Professor Stanton introduced the concept of nanoseismology, probing a material using surface acoustic phonons, before concluding with a discussion on the tremendous potential for Terahertz technologies. I found the applications of Terahertz spectroscopy for biomedical imaging to be extremely interesting, since I absolutely loathe getting dental x-rays. The lead apron and the heavy sensor you have to hold in your mouth for what seems like hour upon end make going to the dentist a very uncomfortable experience that could be improved tremendously with Terahertz spectroscopy.

Professor Stanton’s lecture was my first introduction to the concept of coherent photons and the amazing things that they can do (creating a Chinese finger trap out of a carbon nanotube by using coherent photons to manipulate its radial breathing mode is one of the coolest things I’ve ever heard of). If there are any articles out there that provide a more general overview of the manipulation and applications of coherent photons, please point me in the right direction.

Otsuji-sensei’s lecture also touched on Terahertz imaging, but focused more on graphene. Graphene’s unique transport properties make it suitable for implementation in photonic devices. It has a giant mobility, and its surface plasmons greatly enhance the gain in Terahertz emission after laser excitation; optically pumping graphene causes band-to-band optical phonon scattering. Otsuji-sensei told us that graphene has the potential to bridge the Terahertz technology gap, and current-injection graphene Terahertz lasers are likely coming soon. At this point, graphene is a mythical wonder material in my mind, and I get to start working with it tomorrow. Otsuji-sensei’s and everyone else’s lectures have made me extremely excited for my first graphene experiment. I very much appreciate the articles and answers I’ve received so far concerning my project, and I’m sure I’ll be learning a lot this week.

My first day in the lab involved a lot of paperwork and a lot of walking. I started my morning with a train ride from the hotel I’d been staying at the night before (my dorm only allows me to check in on weekdays), generously escorted by a few of the Tonouchi Lab graduate students. One was quite friendly, and tried his best to talk to me in English, while the other was more reserved, shying away whenever I tried to ask him questions. The walk from the station to the lab was surprisingly far, requiring a steep uphill trek through a park that made me regret my insistence on carrying my own luggage.

When I finally arrived in the lab, the secretaries were very excited to greet me, and I was able to begin passing out the omiyage I brought, assorted beef and turkey jerky wrapped with Texas tissue paper for the secretaries and senseis, and Tokyo Tower chocolate cake snacks for the graduate students. The secretaries introduced me to a few other graduate students in the lab as well as Kawayama-sensei, a very helpful and friendly associate professor who will be overseeing project in the weeks to come. They said that Tonouchi-sensei was preparing for his trip to America and might not be able to see me before he left, but he was going to try his best to come in and meet me. The secretaries then gave me a large stack of paperwork to fill out and sign, and the rest of my morning was spent delivering the paperwork to various offices.

After all of the required forms were turned in, we returned to the office to go to lunch as a group. The secretaries chose a restaurant that one of the graduate students worked at part time so they could introduce me to him, and I was able to try kitsune udon after a slight mishap; the first bowl I was served had a piece of shrimp tempura in it, and I have a severe shellfish allergy; it was generously replaced by a runny egg. While at lunch, I noticed a surprisingly large language barrier between the graduate students in the lab. The Tonouchi Lab is very international, with students from Bangladesh, Madagascar, and the Philippines, but it’s clear that those students don’t speak much Japanese. In fact, people at the table were joking about how much better I was at Japanese after only three weeks than another graduate student who had been working in the lab for a year and a half. This is a bit alarming, since the Japanese students in the lab don’t seem to speak much English.

After lunch, when I observed the students working in the lab, I was shocked to discover how divided the lab is. The international students work with other international students, and the Japanese students work with other Japanese students with a surprising lack of overlap. I observed an international student trying to ask one of the senior Japanese graduate students a question in English. When he responded, the student told him that he couldn’t tell if he was speaking English or Japanese, and walked away. It concerns me that the lab is so divided, since collaboration is essential to scientific advancement. I’m also concerned that my graduate student mentor Kawano-san and the other graduate students I’ll be working with are in the Japanese “clique” and don’t have much experience speaking English.

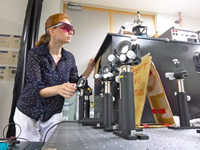

The language barrier hasn’t been too much of a problem with my lab work so far, but it’s certainly been an inconvenience. I’ve spent the past week assembling the Terahertz system I’ll be using this summer, and it’s been going well. Kawano-san tries his best to explain what’s happening in English, but it’s easier for me to just observe what he’s doing and repeat it. He often shows me a task to do and then leaves to work on some other project, so I work alone bolting down equipment, aligning the laser, and trying my best not to mess anything up. Right now, my goal is to have the entire system assembled in two weeks so I can begin exploring the relationship between the substrate used and the optical and electrical conductivity of graphene.

Working alone and eating lunch with lab-mates who don't want to speak English has been a bit isolating, but I’ve been making good progress on my project. The only major issue I’ve had about the lab is my commute. My housing is very far from my lab. In total, it takes forty-five minutes to get to the office, with a fifteen minute walk to the train station, a five minute train ride, and a twenty-five minute walk to the lab. The walk is over several large hills and quite strenuous, so even though I’m not required to arrive in lab until 10:00 a.m., I leave at 8:30 to avoid some of Osaka’s infamous heat. The commute back is particularly difficult, because I usually buy groceries at the station at the end of the day, and then have to carry them up a steep hill back to the dorm. One of the secretaries offered me an alternative to walking/train-riding, riding a bicycle, but she said that the road I’d have to take is poorly lit at night and lacks a good sidewalk and the cars on it drive very fast. She didn’t offer me a helmet. I think I’ll stick with walking for the rest of the summer.

Rice students often say that my residential college, Lovett, has the worst dorms on campus, but Lovett looks like a reasonably priced timeshare in a scenic part of Florida compared to the Tskumodai International Student House. There are very concerning memos everywhere reminding occupants not to spit in the kitchen sink (which consistently smells like rotten eggs), not to break windows, and not to leave excrement on the bathroom floor. The kitchen apparently has a mouse and cockroach problem, and the rooms have nauseatingly bright fluorescent lighting, but the air conditioning works and I have a modem in my room, so I can’t complain too much. I will however be very excited to move back into my palace of an apartment when I return to the States.

This is my room at the Tskumodai International Student House. I’ve already started decorating the shelves with some of my souvenirs from Tokyo, and next to the fridge you can see the beautiful “croc-offs” I bought, the epitome of practical lab footwear.

Exploring Umeda: Lisa and I took a day trip to Umeda on Saturday and had an amazing time. The weather was perfect, and there were tons of shops and restaurants to explore. I was even able to find the perfect swimsuit for the mid-program meeting in Okinawa!

Research Project Update

THz-TDS Setup (Week1): The fruits of my labor from the past week, a (mostly) aligned laser setup. The next step is to install the vacuum chamber that holds the samples.

The purpose of my project is to understand more clearly the effects of temperature, substrate used, and absorption of gas molecules on the fermi level of graphene. While these factors are all known to affect the conductivity of graphene, an exact relationship has never been established, and it will be my goal to determine that relationship and develop a mathematical relationship to describe it.

The primary tool I’ll be using to explore this relationship is Terahertz time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS). I have a unique opportunity to learn about THz-TDS, because I’ll be working from the ground up on a new system. Since temperature is a variable I’ll be exploring with my project, ambient temperature control is essential, and the THz-TDS system that the Tonouchi Lab originally had was in a room with poor temperature regulation (it had a window). To overcome this issue, it was decided that the system should be moved to a new room, and it’s been my job to move it. Being involved in every stage of the assembly process has made me appreciate the intricacy of the beam path and understand the effort that goes into alignment. Since I know the setup well, I should be able to troubleshoot issues much more easily than if I’d just walked in and started a THz-TDS experiment.

In addition to the home-built THz-TDS system, I’ll be using a commercial Raman spectroscopy instrument to identify samples of graphene on various substrates, including gallium arsenide, indium phosphide, and magnesium oxide. I’ll be using samples that have already been prepared rather than synthesizing my own. One issue that has come up in my research so far has been that everyone keeps asking me if I brought samples from Rice. Was I supposed to have been given samples prior to departure? Everyone seems very disappointed when I tell them I don’t have any.

One of the important aspects of my project is to separate the effects of the substrate and gas molecules. To control the variable of gas molecule adsorption, samples are measured and stored in a vacuum chamber, and heated prior to data collection to vaporize any lingering gas molecules. The storage case of all of the graphene samples has an elaborate system of tubes to keep everything under reduced pressure. I haven’t needed to retrieve any samples yet, but hopefully I’ll have supervision when I do. My greatest fear right now is turning the wrong lever and flooding the storage case with air instead of restoring the vacuum, sending samples flying in all directions and ruining them completely.

Since I’ve been working on building the instrument, I have not yet learned how to set up a graphene experiment, but I’ve received some basic training with the software used to graph data, a program called Origin. Origin is much more intuitive than MATLAB, and the graduate students were kind enough to install it in English for me, so hopefully by next week I’ll be able to include some graphs of initial data in my research update. Data is collected using LabVIEW, a program I’m familiar with, and all the programs I need seem to have been written already, so I won’t need to receive any additional training on that front. When I get to the “develop a mathematical model” portion of my project, I’ll need to receive more training, but I’m happy that I’ll be working cozily inside my comfort zone for the time being.

It’s been difficult to establish an exact timeline for my project, because Tonouchi-sensei has been away at a conference. I told Kawayama-sensei about the deadlines for my poster, but the only definite goal set has been to completely finish the Terahertz time-domain spectroscopy setup I’ve been working on in two weeks. Perhaps when Tonouchi-sensei returns, I’ll be able to develop a more thorough timeline, but for now, I have a goal and a deadline. I’ll see what happens after that goal has been accomplished.

Since I’m currently between Japanese language classes, for the past two weeks, I’ve been trying to coast on what I learned during the orientation in Tokyo. I’ve been able to get by pretty well for the most part. I’ve been able to ask for directions, ask what certain foods are and if they have certain allergens in them, and ask for separate checks. I haven’t stopped learning Japanese entirely. One of the graduate students has been teaching me useful kanji with intermittent pop quizzes, and I’ve been picking up some technical lingo here and there. But there are certainly blind spots to my knowledge, and a blatant one appeared during a minor crisis in Kobe.

Lauren and I were having a lovely day exploring Sannomiya and Nada. We had a delicious Kobe beef lunch at Wakkoqu, one of the highest-rated restaurants in Kobe, and toured the Hakutsuru Sake Museum, learning about both old and new techniques of sake-making. It was shaping up to be a lovely evening as we took the Shin-Kobe ropeways up to the top station of the Nunobiki herb garden. The views were spectacular. I took entirely too many photos on the way up, and once we got to the top, I couldn’t seem to help taking picture after picture of the gardens and sprawling city below.

We decided to do a bit of shopping for omiyage. There were lots of treats for sale made using herbs grown in the garden: lavender cookies, rose tea, and locally-raised honey. We looked around briefly before deciding to go up to the terrace first and enjoy the view while we could; it looked like it was going to rain soon. When we got to the top of the terrace, there was yet another spectacular view, so I reached into my purse to grab my camera.

My camera wasn’t in its usual pocket. I dug around my purse, growing concerned. My camera wasn’t in my purse. It was lost. I started to panic. I realized that I must have set it down while shopping and forgotten to pick it back up. Quickly, I retraced my steps in the gift shop, but it was nowhere to be found. My stomach sank. Someone must have stolen it, and all was lost.

Not only were my irreplaceable photos of my once-in-a-lifetime lunch from the gods of deliciousness gone, so were high-quality photos for the rest of my trip. What was I going to do without the “through glass” setting on my camera for towers and glass display cases in museums; how was I going to upload photos for the remaining weekly reports? I wanted to find a remote corner of the garden, curl up, and cry, when Lauren suggested asking the gift shop cashiers if they’d seen it. I was glad to have something to do besides weep for my loss, but I certainly wasn’t hopeful. The person who found my camera was probably already half way down the ropeway, deleting my photos and using the wrong setting to take poorly-composed new ones. We went to the checkout counter to ask about the missing camera.

As soon as I got to the counter, I realized that I had no idea how to say that I lost my camera. I knew how to say I didn’t have my camera, but I doubted that the cashier would understand. Fortunately, I’d brought an English-to-Japanese dictionary with me since Lisa didn’t come with us, and I began flipping through it, frantically trying to find an entry on “lost.”

There was an entry on “lost and found,” but I was so distressed at that point, that I could barely sound out the roomanji Japanese translation. The cashier must have seen that I was struggling, and said, “Information,” gesturing to the right. Assuming she meant that there was an information desk in that direction, I headed over to the right side of the store. We paced around for a few minutes, but couldn’t find the information desk. Assuming defeat, I went back and asked the other cashier where the “information” was in Japanese.

She was very helpful, and walked us over to a small desk we’d overlooked, ringing a bell to call over the information desk receptionist. Less than hopeful, I told her, “Watashi no kamera, nakunatta,” meaning what I think is, “My camera, it is lost.” She immediately began gesturing, tracing a rectangle in the air with her fingers. I can’t remember if she actually said the word “case” in English or if my latent Japanese language skills kicked in at this time of crisis, but somehow I understood. She was talking about a camera case, and it just might be the one surrounding my camera.

Tentative relief swept through me. I immediately nodded excitedly, saying, “Hai, blue!” (I couldn’t for the life of me remember the Japanese word for blue.) She told me, “Chotto matte kudasai,” and disappeared behind a curtain behind the desk. She returned with my camera.

I couldn’t believe it. All of the rumors about Japanese respect and caring and not stealing other people’s things were true. I immediately realized how ridiculous I must have looked to the cashiers and the receptionist. I shouldn’t have assumed the worst before asking, but I was so accustomed to the American big city mentality that if something is lost, it’s lost for good. When I got my camera back, there were no random photos that someone else had taken, there was no ransom note demanding a reward. The person who found my camera probably didn’t even take it out of its case; he or she probably turned it into the information desk, and went back to shopping without a second thought.

Getting my camera back to me seemed like a one-in-a-million reunion. To the receptionist, it was just another perfunctory task. She told me to fill out a form with my name, address, and phone number (I assume just in case I was taking the wrong camera), and that was it. There was a slight misunderstanding when I couldn’t remember what “jusho” meant, but when she said, “your stay,” I remembered it meant “address.” I thanked her wholeheartedly, and I went up to the terrace to take a triumphant photo.

My critical incident didn’t really have any major misunderstandings; the situation was just exacerbated by my unnecessary panic over my lost camera. I was so grateful that everyone was so calm and helpful rather than sharing in my hysteria or worse, avoiding me because of my crazy gaijin panic attack. Next time, I’ll have more faith in Japanese culture, and I won’t let my American assumptions get the best of me.

Domo Arigato Gozaimashita: This is the photo I was able to take because of the incredible generosity and honesty of the random person who found my camera. I realize that the chances of that person ever reading this are slim to none, but I’d still like to thank them with all my heart and dedicate this photo to them!

Research Project Update

I spent my second week in the Tonouchi Lab trying my best to optimize the amplitude and signal-to-noise ratio of the Terahertz Time-Domain Spectroscopy system I assembled the previous week. My mentor Kawano-san was sick with a fever for most of the week, so I tried my best to work on my own, but I worry that I wasn’t as productive as I could have been had he been there. Even so, I was able to discover a way to reduce vibrational noise in the system and have it ready for my first THz-TDS measurement of gallium arsenide and graphene on gallium arsenide next week.

Monday of week two was yet another day of registration. Since Kawano-san was sick and there was no one else who could oversee my project that day, Kawayama-sensei told me to study some articles in the morning, attend a guest lecture on superconductors in the afternoon, and get my fingerprint registered so I could access Osaka University’s 21st Plaza Building whenever I wanted after the seminar. I now have 24-7 access to my THz-TDS system, so once I’m far enough along on my project that I can work independently, I can start coming in early to work on my project rather than arriving early and waiting around until someone gives me a task to do.

On Tuesday and Wednesday, I tried to fine-tune the system and troubleshoot a few issues, the main issue being the large amount of vibrational noise in the system. I started out with the slightly-less-than-scientific approach of gently tapping each component of the beam path to see if it would affect the amplitude reading of the system. Surprisingly, I found that when I touched the base of the emitter, the amplitude reading would quiver violently, so I tried to better secure the base to see if that would stop the wild changes in amplitude. Securing the base of the emitter did seem to help a bit, but I discovered another approach that reduced the signal-to-noise ratio even further.

I can’t quite remember why I ended up trying this, but I found that by defocusing the emitter, the amount of vibrational noise was significantly reduced, but the amplitude decreased as well. I immediately began trying combinations of defocusing and focusing the emitter and detector, and found that a defocused emitter and focused detector was the best combination to reduce noise, while a focused emitter and focused detector was the best combination to maximize amplitude. For the purposes of my project, low noise is more important than high amplitude, so I’ll be using a defocused or “zoomed out” emitter and focused or “zoomed in” detector moving forward.

Kawano-san finally recovered on Thursday afternoon, so we began assembling the final component of the system, the box that houses the emitter, detector, parabolic mirrors, and the vacuum chamber that holds the sample. Once that was complete (it took a bit longer than expected, because Kawano-san accidentally dropped one of the panels of the box and misaligned a component of the beam path), we brought in a barometer and vacuum pump for the system, and left for the weekend, ready to gather our first graphene data on Monday.

On Friday, I gave a short update on the progress of my project at group meeting, and I’ve uploaded it to OwlSpace. During my third week, I’ll finally begin taking THz-TDS measurements of graphene, but for now, all of the attached data is of blank samples. Tonouchi-sensei has also asked that I give a small talk on THz-TDS and graphene this coming Friday, so I’ll be preparing for that as well this week.

The Tonouchi Lab might not be a typical Japanese research lab. The hierarchy lines are blurred, there are several international students, and the Masters students have mastered the “American yes” and “American no.” When I came to the lab, I expected there to be much more structure and to work very rigorous hours, but instead, I found myself playing Nintendo 64 during afternoon breaks and going home before sunset. I’m not sure if the Tonouchi Lab is a definitive model for research in Japan, but it certainly seems to be an effective one, and one that I very much enjoy being a part of.

There aren’t really any defined “rules” that I’ve observed that dictate interactions with fellow Tonouchi Lab members. When someone has a question, they ask it freely, and no one seems to be holding back any opinions. One of the international graduate students responds with, “yes sensei” whenever Tonouchi-sensei or Kawayama-sensei tells him something, but he seems to be an isolated case.

As far as addressing goes, the Senseis are addressed as such, but the graduate students address each other using the kun honorific, and the Senseis use the kun honorific for everyone. The secretaries call me Nicole-chan, and the graduate students simply call me Nicole. I’ve been sticking with the san honorific for the graduate students and haven’t been corrected yet, so hopefully I’m doing the right thing and not offending anyone.

Everyone seems to get along well, and I haven’t noticed any major disagreements. A fourth-year undergraduate member of the lab once complained to me about Tonouchi-sensei’s insistence on him studying for graduate school examinations rather than working on research, but as far as I know, he’s never voiced his concerns to Tonouchi-sensei. He probably trusts in Tonouchi-sensei’s judgment, and is willing to follow his suggestion, even if he thinks his time would be better spent elsewhere.

The lectures Professors Kono and Fons gave during the orientation contained lots of helpful background information about the research we’d be doing and the process of adjusting to life in Japan, but little was said about the daily life of a typical graduate student or typical research dynamics, so I didn’t really know what to expect going in. My alumni mentor JJ talked about biking home at night after long days in the lab, which worried me a lot. I walk to and from work every day, and my commute takes me through a poorly-lit park with a poster at the entrance depicting a man in the shadows sneaking up behind an unsuspecting young girl. Walking home alone in the dark was something I didn’t want to do. Fortunately, all of the graduate students have been very understanding of this, and always tell me, “That is all for today,” in time for me to get home before dark. Perhaps I’ll have to stay longer hours once the symposium starts approaching, but for now I’m very pleased with my work schedule.

Working in a Japanese research lab hasn’t been too different from working in a U.S. research lab, but there have been some differences. Perhaps the biggest difference between Japanese and American research is Japan’s value of obtaining precision and perfection over results. I finished assembling my Terahertz system rather quickly, and expected to begin experiments with graphene as soon as it was finished. But instead of jumping in and taking all sorts of measurements of graphene, the graduate students insisted on trying to optimize the system first, working to find a way to maximize the amplitude and signal to noise ratio for a blank sample.

Optimizing the amplitude was often a tedious process, and it took me much longer to adjust the system than other members of the lab. I remember getting so frustrated when I was trying to align the detector and the signal dropped by fifty arbitrary units, fifty arbitrary units that had taken me at least thirty minutes to achieve. I was frantically scrambling to fix what I had done when Takayama-sensei, the lab’s technical assistant, walked in. I was so ashamed that I had just ruined the alignment, but he simply turned his head to the side, told me, “I try,” and began rapidly adjusting nobs. The amplitude rose by seventy arbitrary units in just a few minutes. Takayama-sensei then motioned for me to resume the alignment.

While I was happy that I didn’t do any permanent damage to the system, I was also a bit confused, and a bit frustrated as well. I thought that I was making a significant contribution by optimizing the system, but Takayama-sensei could do it in less than a tenth of the time. Furthermore, when another graduate student walked in and saw my progress, he was amazed by how high the amplitude was, saying that it was more than enough for the types of experiments I’d be doing. Why then was I wasting my time? The answer became clear when Takayama-sensei again checked on my progress.

I asked him if he’d like to try aligning the system, hoping that perhaps he’d finish quickly, and I could start on something more important, but he declined, saying, “It’s more important you understand.” I then realized why he had let me struggle for hours when he could finish the task in a few minutes. He thought that it was more important for me to know how to achieve a high amplitude than for me to achieve a high amplitude. While research labs in the U.S. certainly value technical understanding, no lab supervisor would have had that level of patience for me to align the system when there was a technical assistant available who could finish the job so much more quickly, especially since I’m working in the lab for such a short time.

In the U.S., the supervisors are concerned about achieving results; in Japan, they’re concerned about achieving understanding. It’s difficult for me to say which environment I prefer. I certainly wish that I had more presentable data at this point, especially with the mid-program meeting in a few days, but I’m more confident about troubleshooting issues with the system than I would be in a U.S.-style environment. If I didn’t have the pressure of the clock, I’d be fine taking more time to get to know my system, but because of my limited time left, I get more than a little frustrated when I have to do something myself that someone else can do better. I suppose it’s important to just keep working and to continue to follow the two golden rules of the Tonouchi Lab: know your system, and always remember to take your shoes off in the lab and office.

Hieizan Rooftop Views: On Saturday, Lauren and I spent the afternoon exploring the Hieizan Enryaku-ji Temple. The views were spectacular, and the setting very serene. One path took us past secluded shrines, and we found that we were the only ones exploring the area.

Joyous Osaka Tour: On Sunday, some of my lab mates graciously organized a “joyous Osaka tour” for me. It was a wonderful day of castles, aquariums, and traditional Japanese dishes, including takoyaki at one of the most famous shops in Osaka!

Research Update

This week involved some significant steps forward in my research, but also a few steps back. I finally began collecting Terahertz data of gallium arsenide and graphene on gallium arsenide, but I discovered a major issue in the beam path of the Terahertz system that required me to disassemble portions of the system and realign a significant portion of the path. Hopefully now that these adjustments have been made, I’ll be able to move forward and finally begin some of the more specialized experiments for my project.

Since I was able to put the final components of the system in place last week, I finally started collecting graphene and substrate data early in the week. There were a few minor issues aligning the system, since we were still convinced that there was some sort of optimal “zoom in” and “zoom out” combination of the detector and emitter that would magically boost the signal-to-noise ratio, but we were able to collect some waveform data of gallium arsenide and graphene on gallium arsenide. Somehow we managed to forget to collect a reference spectrum of a blank sample under the final settings of the detector and emitter, so the optical conductivity of that particular experimental session can’t be calculated, but all of the data needs to be recollected anyway now that we discovered and corrected a major flaw in the system.

One of the preliminary experiments we conducted was to measure the Terahertz amplitude readings of the graphene on gallium arsenide sample over a fourteen-hour period. We set up the experiment in the evening and allowed it to run overnight, but when we came back the next day, we were surprised to see a plummet in amplitude after three hours of data collection, followed by a steady decrease. This was discouraging data, because some of the temperature experiments we were hoping conduct are long-term, and thus require long-term stability in the system. Even ignoring the sudden drop in amplitude, the continuous decrease in Terahertz power could be a potential problem.

We decided to repeat the experiment during the day rather than overnight, so we could make sure no random disturbances occurred, but while we were realigning the system, Tomita-san tried tapping some of the optics in the beam path to see if the amplitude would change with a minor disturbance. Everything seemed to be fine, until he touched the beam splitter. A gentle tap caused the beam splitter to rotate out of place, and immediately caused the amplitude reading to drop to zero. We tried to put the beam splitter back in place and secure it, but had no luck. We had to realign the system again.

I spent the rest of the week taking the system apart and putting it back together again. It was a frustrating experience, but probably a valuable one as well, since I got more practice aligning the system. I was able to finish in time to set up an experiment on Friday that I was going to allow to run until Monday to test the limits of the long-term stability of the newly-aligned system, but unfortunately, while I was away, LabView decided to suggest a program update, interrupting the data collection only six hours into the experiment. Hopefully I’ll be able to collect some new data this week in the short time I have before I leave for Okinawa, so I have something to present at the mid-program meeting. I won’t have enough time to do any specialized experiments (testing the relationship between the optical conductivity of graphene and temperature, substrate, and surface gas absorption), but I would like to have something to show what my new system is capable of.

Outside of research, my biggest accomplishment so far has been my ability to navigate the various railway networks in Kansai. I started off blindly following my lab mates on the Kita-senri Line to get to work every day, then clinging to an English map of the Hankyu network to get to Umeda and back. Now I’m able to switch lines, strategize my usage of the express trains, and even read the station marquees in kanji (I try to memorize all the relevant kanji for my trip before departing). Granted, I have received some help from Hyperdia, but I’m still proud that if I for some reason miss a train provided on my Hyperdia-suggested route, I can improvise and still make it to my destination.

My biggest personal challenge to this point has been adapting to daily lab life with such a big language barrier. While I’ve had some wonderful and entertaining conversations with my lab mates in English, when we go to lunch every day, they speak exclusively in Japanese, and rarely make attempts to bring me into the conversation. This has been rather isolating, and many times I wish I could make up an excuse so I could just eat lunch on my own rather than feeling excluded, but I know how much that would offend my lab mates. I suppose I should just continue to study as much Japanese as possible so I can try to join their conversations in the future.

My research has been progressing somewhat more slowly than I anticipated, but I think that I’ll still be on track for my Rice Quantum Institute poster presentation and the symposium in Tokyo. Aligning and optimizing the new system has been an arduous process, and because of that, I still don’t have any poster-worthy data to show. However, we began installing the temperature-regulating apparatus before I left, so hopefully when I return, I can hit the ground running on the most important phase of my project, quantifying the relationship between the temperature of the sample and the optical conductivity of graphene.

I probably would have more relevant data by now if I weren’t so involved in the setup of the new system. As I mentioned in my previous report, Takayama-sensei was initially much better at aligning the system than I was, and had he set up the system on his own, I might already be collecting temperature dependence data. However, I think all of the hands-on practice has helped me a lot, and I’m now one of the fastest aligners in the lab. In fact, whenever something goes wrong with the system, I’m now the one to fix it. Hopefully when I go back to the U.S., the Tonouchi Lab will be able to handle the new system on their own.

A lot of the major issues I had at the beginning of my lab experience have since resolved themselves. I haven’t had any awkward encounters with my lab mates because of my gender, and I think I’m continuing to earn everyone’s trust in my experimental abilities. There have been several instances when I’ve run experiments and processed data on my own, and everyone seems to respect my suggestions about how to optimize the system. It’s hard to believe that I started out not even being able to use a screwdriver without constant supervision. Perhaps by the end of the summer, I’ll be designing and executing experiments with complete independence.

I can’t wait to reconnect with the other NanoJapan students and swap stories about experiences both inside and outside the lab. Hopefully everyone is enjoying their research experiences as much as I’ve been enjoying mine.

A Sweet Send-off: On my last day before leaving for Okinawa, we began installing the temperature-regulating apparatus for the system. The apparatus can increase the temperature of the sample but not decrease it, so the system is cooled with liquid nitrogen first, then heated by the apparatus for the experiment. Since we were only doing preliminary tests with the apparatus, we had a lot of liquid nitrogen left over, so my lab mates decided to throw a popsicle party at the end of the day to celebrate reaching the halfway point of my research internship.

Research Update

This was a rather short week for me, since Monday was Kono-sensei and Sarah-san’s lab visit, and I left for Okinawa on Thursday. Even so, I was able to continue to optimize the system and to start focusing on improving the reproducibility of the data collected by the system. Before I left, we began installing the temperature-regulating apparatus of the system, so hopefully I’ll have a brand new experimental element to play around with when I return to lab on Tuesday.

Kono-sensei offered some great suggestions during his lab visit, as well as some much-appreciated encouragement. When I told him about the issues we’d been having with the long-term stability of the system, he suggested avoiding the issue altogether by taking shorter-term measurements. Our original plan was to take data ten times in one position, each measurement taking one hour, then move to the second position and take another ten one-hour measurements. This requires the system to remain stable for 10 hours, and we observed a sudden drop in amplitude after only three hours.

Kono-sensei suggested instead to take one measurement in the first position, then switch to the second position for the second measurement, and continue switching back and forth until all of the data is collected. This method has the slight disadvantage of requiring more time to adjust the position between measurements, but if we’re unable to overcome the issues we’ve encountered with long-term stability, this could be an excellent solution.

I was finally able to move away from alignment-based optimization and instead start to focus on LabVIEW settings. We tried varying the number of averaging points and the time constant to try and find a combination that would maximize accuracy while minimizing measurement time. We found that 30 averaging points and a time constant of 30 was the best combination with our current alignment. We then began collecting data to test the variation of the waveform over ten trials.

My last day in lab wasn’t as productive as I might have liked, but it did feature a very exciting development: the installation of the temperature-regulating apparatus of the system. I started the day by retrieving the liquid nitrogen required to cool the system (the apparatus can only raise the temperature of the sample; it can’t lower it). While we were waiting for the tank to fill up, I mentioned to my lab mates that liquid nitrogen could be used to make ice cream. They’d never heard of such an application before, and were very intrigued.

I spent the rest of the day waiting while a technical assistant installed the apparatus. He was quite boisterous, and seemed to get distracted rather easily, interrupting his work now and then to tell a humorous story (one I think was about ghosts; it was hard to tell since he only spoke Japanese). While some progress was made, the installation came to a screeching halt when we discovered that the software needed to run the new apparatus was missing. We searched around all three of the labs for the missing disc, but had no luck finding it. We’ll have to order a new copy.

I was a bit disappointed that I couldn’t have temperature data to show during the mid-program meeting, but my woes were forgotten during one final experiment I conducted before leaving for Okinawa: using some of the excess liquid nitrogen to make popsicles. We couldn’t find a large enough bowl to pour liquid nitrogen directly into our milk-and-coffee or milk-and-juice mixture and make ice cream, so we opted for popsicles instead, placing the desired mixture in a paper cup, sticking a pair of chopsticks in the center, and lowering the cup into a bath of liquid nitrogen. While I don’t have any quantitative data from the experiment, I can say that the results were delicious.

At the end of the orientation program, I was sleep deprived and exhausted, but I had a pretty significant amount of Japanese tucked away in my memory bank. The classes were so fast-paced, that it was difficult to remember everything I learned in one sitting exactly, but I could often recognize words in basic conversations and get the basic idea of what the speaker was trying to say. Responding was much more difficult. It could be frustrating at times, because while I knew what someone was asking, and I knew I should have the ability to respond because I was taught how in some orientation class, I was unable to calculate a response in a reasonable amount of time for a conversation. Overall, at the end of the orientation, I’d say my understanding of Japanese was at an advanced beginner level, but my speaking skills were more at an intermediate beginner level.

In my lab, I don’t have time to take organized classes, but one of the graduate students has been an incredibly helpful teacher. His lessons have been very informal, focusing more on Osaka-ben than standard Japanese. He often tells me, “This [new word or phrase] is good for every day, but don’t say it to a teacher.” (I’m a bit worried about my upcoming OPI.) He’s also continuing to teach me kanji, although his lessons have slowed down a bit in pace, and I haven’t had a pop quiz in a while. He’s been very interested in learning more about conversational English, so we’ve put kanji on hold, and opted for cultural exchanges of slang instead.

I honestly can’t think of any major issues I’ve had with the language barrier. I can’t really come up with any dramatic stories of miscommunication, just a few minor instances when a waitress said something I couldn’t understand in the slightest, or when my graduate student couldn’t find the words in English to explain some technical aspect of our project. I’ve usually been able to work through with gestures or with simple, pointed questions and manage to still achieve what I wanted despite a misunderstanding.

I’ve been getting a lot of great communication lessons from Tomita-san, but one of the one that stands out to me the most is when he told me that English is hard because people slur their words together. I didn’t understand what he meant at first. I told him that Japanese was sometimes difficult for me, because words are often unpredictably contracted and syllables left out, but he was insistent that that was different; that was with individual words, not with two or more separate words. It finally dawned on me that the typical, flowing, conversational English I’m used to speaking must be difficult to understand, because I don’t break up the words in my speech. A choppier speaking style, while it sounds awkward, is much easier to understand, because individual words can be recognized, rather than getting lost in a long chain of sounds.

I’ve really enjoyed learning Japanese, and I continue to do so by learning words or phrases from Tomita-san and using them for certain situations in lab. It would probably be more practical to learn more about grammatical structure and conjugation, but I often finding myself using short sentences or phrases in my everyday conversations rather than long, elaborate sentences. I was interested in continuing my study of Japanese after the program, but I was disappointed to discover that the introductory Japanese language class at my home university won’t fit with my class schedule, and no intermediate class is being offered in the fall. If I do continue, it’ll probably be through the Language Table program at Rice University, in which you can sit down and have lunch with other speakers of a particular language. This would also be a better opportunity to use the Osaka-ben I’ve been learning, since it’s apparently not fit for teachers.

The Mid-Program Meeting was an exciting and action-packed reunion. I enjoyed hearing about everyone’s experiences and progress so far and exchanging stories. I was particularly interested in Skylar’s Terahertz system; it was essentially a miniature version of my own, constructed using much more sophisticated alignment techniques. It was so helpful for me to talk to someone else who had made their system from scratch and talk about all of the triumphs and travails associated with it.

The key takeaway I got from the meeting is that my research is in a good place. I was initially concerned that I didn’t have enough data at this point, but after hearing from everyone else, I’m pretty much exactly where I should be with my project. I was also pleased to learn that my assignment allows for more independence in my work than some of my fellow NanoJapanners. It made me realize how much my lab members have grown to trust me with the new system and the project. For the rest of the summer, I plan to continue to gather as much data as I can, learn as many kanji as possible, and get the most out of my free time, enjoying what little time I have left in Japan.

A lesson in Umms: Pictured is a transcript from one of the language exchanges I had with Tomita-san, in which we talked about the usage of non-lexical conversation sounds.

Afternoon at OIST: During the Mid-Program Meeting, the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology was vey generous to allow us to use their facilities, tour their labs, and enjoy their spectacular views. The tall, orange-roofed buildings are the student housing Skylar and Julianna have been living in so far. They have a view of the ocean. I have a view of a retirement home.

Research Update

With only one week to go before the first draft of my abstract is due, this week, I was finally able to begin collecting data for my poster. While the processed data I currently have available is somewhat inconclusive, the raw data I took on Friday looks quite promising. I’m a bit concerned that I won’t be able to start the most important experiments for my poster, the temperature dependency measurements, until next week, but hopefully I’ll be able to gather some good data and edit my abstract in time for the Rice Quantum Institute deadline for submissions.

I was unable to attend lab on Monday due to travel back from the Mid-Program meeting, so I had another shortened week. On Tuesday, I was somewhat disappointed to discover that a power surge over the weekend had caused the system to become misaligned, and I spent a fairly large portion of the day realigning it. Fortunately, I was able to finish with a bit of extra time to spare, so I began assembling the box that would allow me to purge the system in nitrogen for future experiments.

After five weeks of meticulous adjusting and readjusting, assembling, disassembling and reassembling, I finally achieved what I hope is the final form of my system. I was able to set up the vacuum and nitrogen lines for the box, as well as take some seemingly stable measurements of the reference spectrum, the substrate, and the sample of graphene on the substrate under vacuum conditions without annealing or purging with nitrogen. Tomita-san assured me that the waveform data was “saikyō” or “super ultimate good,” so I left lab on Wednesday feeling accomplished.

On Thursday, I began testing the nitrogen purging setup of the system. I found that it takes about an hour to purge the system, and the preliminary data I took showed a waveform with much less vibrational noise after the peak, a “super good” sign according to Tomita-san. I also began processing the data I took the previous day of graphene on Gallium Arsenide 110. Oshiro-san showed me how to calculate and graph the transmittance and optical sheet conductivity of the sample using a program developed by a former Tonouchi Lab postdoc. I was quite proud of my first optical conductivity data, and placed all of the graphs in a powerpoint presentation for group meeting.

I was more than a little disappointed when Kawayama-sensei told me on Friday that the data appeared to be unreliable. He said that the large drops in transmittance at a frequency over one Terahertz were unusual, and the fact that the optical sheet conductivity was negative at a frequency of 0.3 Terahertz was also a sign of inconclusive data.