Lisa Chiba - NanoJapan 2014

Rice University

Major: Chemical Engineering

Class Standing: Sophomore

Anticipated Graduation: May 2016

NanoJapan Research Lab: LaSIE, Prof. Satoshi Kawata, Osaka University

NanoJapan Research Project: ![]()

>> Poster Presentation Award Winner

Why NanoJapan?

For me, NanoJapan is the complete package of developing my interests in nanotechnology and research while also developing my perspective as a global citizen. This is one of the few programs geared toward students who have little research experience, and it gives them the opportunity to travel abroad to perform meaningful research in a developing scientific field. It’s an unforgettable adventure in figuring out your passion in research while learning from the people you meet along the way.

I applied to NanoJapan because I wanted to be able to have a productive work abroad experience. With previous experience working in a lab, I know that I enjoyed research and I want to continue defining my interests while also exploring a culture I’ve never truly learned about. NanoJapan will reinforce my decision to continue my education in graduate school, and will give me the experience to be able to succeed in my ambitions of receiving an MS or continuing for a PhD. Not only will this program give me the opportunity to perform research under the top minds in the nanotechnology field, NanoJapan will also instill in me the confidence, independence, and ability to work in a foreign culture that I can apply to any future career. I am excited to learn more about the developing application of nanotechnology, collaborate with people who have completely different life experiences than me, and learn about the Japanese perspective on life and how that applies to my upbringing.

My goals for this summer are to:

When I thought about what this pre-orientation would be like, I expected a nation of solidarity; I thought that this generalization was mostly correct when I arrived. The streets were clean, the subways were quiet and peaceful, and everyone seemed happy and content with their jobs. It’s alien how almost everyone has the same mentality of keeping Tokyo a great city and proactively make personal decisions to meet that goal. It surprisingly takes a lot of effort to stop yourself from eating while walking down the streets. It’s hard to stay quiet on a silent subway platform when you have a lot on your mind. I still have to remind myself to stand on the left of an escalator. Overall, I feel that Tokyo only works because of the people’s attention to detail and the pride they have. At first, I thought it must be such a hassle to have to dress up just to go out in public. But after a few days, I noticed that it’s not a chore, but something they choose to do because of the pride they have in presenting themselves. This attitude is reflected in the cityscape; they have pride and respect for the roads and the subway and as a result they are kept extremely clean and pleasant. I always find myself amazed at how the Japanese have the mutual awareness and courtesy of sharing the environment.

Overall, I feel that my expectations were correct; I found happy people living in a clean city with great optimized public transportation. However, I did not expect that I would have such a hard time integrating myself into Japanese culture. One thing that I did not anticipate was how much work it took to function correctly in Tokyo’s society. At first I didn’t like it. I was always exhausted after every packed day of activities, not only because of the tight schedule but because of the constant concentration and awareness of my behavior compared to the Japanese behavior. My mind was on high-alert at all times, picking up on all of the differences between me and Tokyo. My Japanese side was frustrated at myself as to why I wasn’t like them more. I felt like there must be something wrong with me for my default to be rude or unthinking of others when my Japanese parents had raised me. I was in this void where I felt like I should be more like them because I look like them, but I wasn’t because I was raised as an American. The American side of me was frustrated by what I couldn’t do anymore; I couldn’t be loud when I wanted to be, I couldn’t eat food in the lobby of the hotel I was paying to stay at, I had to stop chewing gum whenever I felt like it. These two overwhelming feelings picked at my mind for the first week, but they were resolved by my realization that I didn’t have to fit a certain culture. I have to stop comparing myself to those around me and just live my life as a product of my environment, experiences, and upbringing.

The language classes are challenging, but enjoyable and I feel like I’m learning a lot. The AJALT teachers do a great job in giving you time to practice speaking it, which is the best way to recall it when you’re using it out in the town. One strategy is to use what you learned in the same day. It feels like you’re learning awkward textbook-situations-only phrases, but you find myself using the phrases from class every day. Also, I find myself thinking in Japanese. If I speak in English, the back of my mind is finding a way of saying it in Japanese. By doing so, you figure out what kinds of phrases you want to learn in the future if your brain ends up failing in finding the words for what you just said. Personally, I found that fearlessness helps a lot in learning a language. The nonjudgmental attitudes of the AJALT teachers allows me to have the confidence to practice out loud, which allows me to see where I need to improve. I suggest that anyone learning Japanese should try speaking more and put less emphasis on writing if time is a factor.

Some questions that have been on my mind

Maybe by talking to the KIP students or other Japanese people, I can understand these topics more.

Left Photo: An escalator ascending into a foyer of mirrors which reminds me of the shiny, modern Tokyo life I expected.

Middle Photo:

Although I can’t fit into the size ‘small’ in a US GAP, I was very happy with the Japanese GAP size selection.

Right Photo: An escalator ascending into a foyer of mirrors which reminds me of the shiny, modern Tokyo life I expected.

So far, all I know about my project is that it will be focusing on using deep UV microscopy that includes fluorescence with applications for bio-imaging. At first, I was told that my project would analyze nonorganic materials, but now that Kawata-sensei emailed back about using DUV microscopy for bio-imaging, I think I will be focusing on analyzing the optical properties of cells. A cell is 3D and I think it’s a semiconductor. My material is interesting because it’s alive, and that you can see the different parts of a cell through DUV microscopy.

There are many unwritten rules that people follow while using public transportation. People generally sit when they can, or stand when they are tight on time and must get off the subway quickly. I noticed that people sit in a way that is convenient for everyone when the car is crowded; for example, if there is a choice in seating on a bench between a seat next to someone and a seat far from that person, the rider will sit next to the person even though she has the choice to sit anywhere. This seems to be because there will be a more convenient space for those sitting later. However, when the time is not busy, it does not seem that people care as much. Forget personal space, because during the busiest times, you will be squished against everyone for space in the car. For this time of day, it is inconvenient to wear a backpack as this takes up valuable space where one more person could have stood. Cars are generally quiet, so it is not a problem to have so many bodies in one car.

People are most likely checking their phones or sleeping on the subway. Sometimes I see people reading books, but the majority are surfing the web, playing games, or checking their email on their phones during their ride. Even older businessmen are well-versed in playing games during these rides. In contrast, people do not eat, drink, chew gum, or talk loudly in the subway. People generally stay out of each others’ way, and performing these activities would be hindering someone else’s experience on the train.

I would say that the rules for politeness and appropriateness are not so different from the US, it’s just that Japanese people do a good job in following through in them. Respect in America can also come in the forms of not talking loudly, or eating/ drinking in important places like the Ritz Carleton, etc. The difference is how much value we place in the subway. The Japanese are extremely respectful of others even in public, shared spaces like the subway. While Americans practice the rules of not eating/drinking, chewing gum, talking loudly in very respected places, they do not go out of their way to act politely in public areas such as subways.

Public transportation is much more pleasant in Japan than the US. In the US, public transportation is riddled by homeless, dirty, dangerous people who even approach you begging for money. It’s an uncomfortable experience and is generally the mode of transportation for those who cannot afford a car. In Japan, businessmen, businesswomen, school children, old people, and young people all use public transportation. There are generally no suspicious people who you must avoid when riding. The cars are clean, quiet, and are an effective means of traveling around the entirety of Tokyo. I am excited to take public transportation in Japan—a stark contrast to living in Houston, where I avoid it if possible.

Through personal reflections, I have learned that Japan is deeply rooted in traditional values. The differences that I observe are sometimes practical (such as allowing others to push against you in a crowded train car), but these differences are rooted in cultural differences. Even when it comes to the environment, the Japanese all proactively choose to behave in ways to conserve energy and materials. For example, most soaps and shampoos are also sold in bags as refills, so you don’t have to continually buy a shampoo bottle when you run out. It’s almost silly thinking that in the US, I buy a new plastic bottle of shampoo whenever the contents run out. The perfectly functioning bottle is thrown away and replaced with another unit of shampoo. This is such a waste of energy to create the plastic bottle, and a waste of material used for the bottle. The Japanese are able to have refills sold because of this unified cultural value of conservation. Thus, the Japanese differences are practical but are rooted in the difference of culture.

On the subways, you can see the Japanese values of harmony, the hiding of honne in order to support harmony, and shared values. Harmony comes in the form of quietness. People generally limit their conversations with each other on the subway, and you rarely see people talking on the phone. The silence in a subway car is peaceful and promotes a more calm, harmonious environment for everyone. I had the experience of trying to offer a seat to a lady holding a baby and pushing a stroller. I was sitting in the area designated for the elderly, injured, or pregnant, so I immediately offered my seat. However, the lady kindly refused, assuring me that she only had a few stops left. I sat down, thankful that she was getting off soon so I was able to sit during the long ride to my specific stop. However, when I woke up six stops later to get off, I saw the same lady still standing next to me! I was embarrassed to think that she stood the whole time carrying a child, when I able to stand easily. I realized that when she said she didn’t have too many stops left, she was probably just trying to be polite and not disrupt the harmony in the car by bothering me to stand up. I left the station feeling guilty, because I felt I should have assured that it wouldn’t have been a big deal for me to leave my seat. Finally, you can perceive the shared values when you scan the floor of the car; litter is nowhere to be seen. Even in the station, the ground is kept spotless by a cleaning staff. This shared value for cleanliness and respect for shared environments is evident in the immaculate cars and stations.

Asakusa: Old Japan meets modern Tokyo.

Intro to Nanoscience Lectures

Professor Bird’s first lecture covered heterostructures and how bandgap engineering depends on choosing layers of semiconductors with different bandgaps. His second lecture covered the advantages and disadvantages of the use of graphene for future electronic devices. Graphene has many promising features from having no gap between the conduction band and valence band, but this also hinders its potential for integration into electronics because the current cannot be turned off. Dr. Bird voiced his opinion that the switch to graphene will most likely never happen because of the deep integration of silicon in electronics. I found this presentation interesting because there is so much hype for the buzzword “graphene” that we all look toward it in excitement. With all of its useful properties such as great strength and mobility, it seems to be the next step in more efficient electronics. However, Dr. Bird presented the inherent problems with graphene that I have not heard before. I enjoyed learning about the other side of the graphene excitement, because before the lecture, I wondered what the downside would be. Dr. Bird explained the downside thoroughly, and I feel that I can now develop a more educated opinion on the use of graphene in electronics. I wanted to ask more about the first lecture; is having materials that are lattice matched only important for the growth of the heterostructure, or is it also important for the positioning of the quantum wells?

Professor Maruyama from the University of Tokyo came to present his lab’s work on the synthesis of graphene. I was very interested in the way he explained that carbon nanotubes can be made of any configuration by simply cutting up a graphene sheet in different ways. I also was interested in the solar cell he displayed that powered a motor to rotate a model in order to show the application of carbon nanotubes. He also showed the progress of synthesizing graphene throughout the years, and it was very impressive to see how much bigger Maruyama-sensei was able to create it. He said that even 10 years ago people were doubting that graphene could be made at a larger scale, but Maruyama-sensei was able to show that it was possible when he made a 5mm-wide flake. It’s exciting to anticipate how much more progress we can make toward the synthesis of graphene, especially when no one thought it could be done.

Prof. Ishizaka, also from the University of Tokyo, talked about her research pertaining to photoemission spectroscopy. Her research was very heavy in technical information, but I enjoyed hearing her perspective as a female scientist in Japan. However, she did not go into detail about any kinds of hurdles she faced as she climbed to associate professor status. She said that she has no idea how to get women interested in science, as she was just naturally inclined toward math and science at a young age and excelled in it versus history or language. Her graph that visualized the dearth of women in science at top-tier universities was eye-opening; female professors are few in Japan, but also are almost just as few in US schools like MIT and CalTech. We may be thinking this is a big problem in Japan particularly, but in reality it’s a global issue.

Kyushu was the Japan I think we were all anticipating when imagining our experience this summer; the humble houses scattered throughout the forest, quiet one-way roads weaving through the hills, the cold air wafting into your room in the morning to wake you up for the new day.

I felt like I came home when I looked out of the bus’s window. Even though I’ve never visited Kumamoto, something about the quiet existence far from the city felt very familiar. However, the difference between my hometown in the US and this rural town in Japan is that the houses peppering the landscape in South Dakota seem forcibly planted in the wilderness. In Kumamoto, the community felt integrated into the surrounding nature. I felt so much more comfortable out there than stuck in the busy Tokyo lifestyle.

I expected this trip to be sort of a vacation where I would forge a deeper understanding of the Japanese culture while I recognizing more similiarities between me and Japanese students of the same age. I also expected to see breathtaking scenery. I ended up taking back with me a lot more than I thought I would. I would say that I am still noticing a lot of differences between me and Japanese people of the same age, but interacting with the high schoolers in a less academic setting when we made the waraji sandals allowed me to really see what Japanese high schoolers are like. It was a lot easier to talk with them, and without the pressures of talking about a set subject, you could really see their personalities when they ogled at how tall Ben was, or how the girl co-leading the activity, working hard running around helping all of us, said with sass “don’t think about escaping from me” when the attention span of the boy co-leader turned to something else. Seeing their personalities come out in an informal activity was the first time I felt a kind of mutual understanding or shared habits with the Japanese students.

The homestay had the greatest impact for me. It was the first time the NanoJapan group had been separated, so it was a great experience learning and thinking by myself. I did not anticipate the kind of life-changing epiphany I had over barbeque with my host parents. My host family was what I imagined them to be; they were an older couple who owns a house carved into the mountainside. The family owned rice fields, a shiitake mushroom farm, tea leaf fields, and chickens. We spent most of the evening at a kind of picnic shelter that was powered by a water wheel. The wheel was driven by a cascade of fresh water from the top of the mountains; I asked if it was safe to drink and my host dad was almost surprised that I would assume it wasn’t. It was kind of liberating to drink from water coming from the mountains, and it was exciting to be immersed in a lifestyle based on creating food and water for yourself without relying on modern conveniences like konbinis and grocery stores. When the sky grew darker, the stars started to come out. The combination of staring into the distant mountains sitting by a fire watching the world fade to black really put time in perspective. In contrast to the city life where you rely on a schedule and a watch, the falling nighttime was a natural end to a day, and when I saw it I felt like time was so finite. No matter how much time you need, or how many things you have to check off your schedule, the earth will continue to turn and you’ll miss one more sunset to watch. And as the darkness engulfed the entire sky, I felt that I had been missing so many sunsets. I’ve been forgetting to think about the big picture, that I have only one life, and I shouldn’t spend it living someone else’s dream for me, or that I shouldn’t spend it without asking myself what I want. And when the stars came out, I thought about how crazy it was that I was sitting in Kyushu because of my own volition to pursue this experience. I sat there realizing that there truly is nothing that can prevent me from living the life I want. If I wanted to uproot and move to Japan, I could do that. If I wanted to live in the mountains and watch the stars every night, I could do that too. Before coming to Kyushu, the impression I got about adulthood was one of rigid linearity—you graduate, you join the workforce in a career you mildly enjoy at times, and eventually die. Going to Kyushu reminded me that I don’t have to be trapped into the typical average lifestyle that I imagined for myself; in the scheme of things, I’m the only one limiting myself from doing what I really want. What do I want to accomplish on this earth? What gives me actual happiness? These questions ran through my head as I leaned back and watched the night sky.

I also thought about how I am meeting all of these people, and how I am probably never going to see them again. It’s interesting to think that as I keep experiencing events in my life, these people will also be experiencing totally different circumstances without me. I want to be able to share my experiences with everyone, but the reality is that we have to choose who we share our experiences with. The sad realization that I won’t be able to be with these students, grow with them, and experience things together after I leave Tokyo nags my conscience, but I know that I can at least stay in touch through social media.

I guess you could say that what I experienced was enhanced by the fact that I was contained within my own thoughts. This was caused by the fact that the biggest challenge staying in the home was communication. The father would talk to me so much so quickly that I couldn’t really process what he was saying that well. I felt really frustrated that I could only say simple things that were merely comments on things he would show me or tell me. I was unable to speak about how I felt, and that was such a frustrating barrier to deal with because you feel unable to express yourself. I feel like I have many instances in life where this happens to me though, so my remedy is to usually get lost in my thoughts and keep the frustration down by concentrating on what the host family was saying and trying to come up with something to say about what he is showing me.

The cultural differences I found with my host family were expected, especially with the woman of the household; my host mom’s job was to make sure everything ran as smooth as possible. She fed us, cleaned up after us, arranged the bedding for us, all with minimal conversation. Even at the water station at the barbeque, she would sit a table away from me, the KIP student, and the host dad like a lingering shadow and quietly listen to conversation. I also felt the deep connection to nature that the Japanese hold; most of the foods I ate came from their garden outside, and it was pretty awesome to be able to go outside and drink the water pouring from the hills. It was almost kind of disgusting that food that has traveled hundreds of miles to end up on my plate is normal to me. To be honest, I was scared to try the fish served for dinner at the inn, simply because its entire body was preserved and staring at me. If I don’t recognize an actual fish body as food because I’m so used to it being a slab of packaged meat in HEB, there is something seriously wrong with my perception.

My experience in Kyushu was pretty valuable for my next chapter on this journey. I learned that having a more natural interaction with Japanese people, like a fun activity making waraji, is more conducive toward seeing similarities. I also indirectly learned that life is what I make of it, and with my limited time, I need to start deciding for myself what I want to do or who I want to meet instead of deciding based on everyone else’s opinion. I also gained a very strong desire to learn Japanese, because I think I’ve somewhat overcome the apprehension that’s seized a majority of my life. Finally, I feel like I personally want to do it, not because I’m expected to or that I should want to do it. I want to do it for myself, and the kind of shame I had before for “letting my family down” or for the embarrassment of not being what I was born into is subsiding. After seeing the bigger picture of life, I realized that it’s only me that’s stopped me for most of the things I’ve wanted to do. I think the time experienced away from the other NanoJapaners and in a completely foreign environment really helped me learn more about myself.

Images of Kyushu

Overview of Orientation Program and Language Classes

The most helpful experience of the orientation was going to Gokase and working in the high school for the discussion and making waraji sandals. Talking about culture at the Sanuki Club is interesting and interacting with Tokyo teaches me a lot about Japanese culture, but talking to the high schoolers of Gokase and seeing how their school runs was a candid snapshot into the life of a young Japanese person. Especially during the waraji making activity, you could see the personalities of all of the students as they tried teaching us how to make them. No cultural class can teach you about the common humanity we all hold; it’s something you can only experience sitting in a school auditorium throwing pieces of straw at each other like children with the Japanese students. The least helpful would be some of the lectures that were given. I wish they could have been condensed some of their material, as sometimes I felt lost in all of the details. That being said, I would say that they were fairly helpful, but there could be improvements.

The most helpful experience from [Japaense language] class was when we went on tangents from the exercise we were working on. The exercises were a good foundation, but I really enjoyed asking about what other things we could say in a certain situation, or what kinds of contexts we could use our exercises for. Some strategies I developed to help learn Japanese

I think the most important thing that I know now since arriving in Japan is to be happy and proud at what you do whatever you decide to do. When I see the subway station officers wave in the next train, they do so with so much pride and as a result I respect whatever they tell me to do. When you have pride in what you do, it doesn’t matter what others think.

Intro to Nanoscience Lectures

Dr. Stanton discussed the basics of solid state physics, and applications such as LEDs and solar cells. He discussed why silicon is bad for optical analysis because it has an indirect gap, which means it’s not optically active. He also said that metals are not good for optics because they reflect. For solar cells, he put everything in perspective by showing us a picture of a solar panel powering a blinking crosswalk light. The solar panel was kind of clumsy looking because of how big it was in comparison to the small light it was powering, showing us that with the efficiency that we have today, solar cells still have a long way to go before large-scale use. He also discussed what a homojunction was, and that a solar cell is a reverse bias p-n junction. Tying in the solid state physics basics, he emphasized the fact that a gap is needed for transistors and optical materials. The gap energy can be analyzed to see what photons will be best absorbed. This is important for solar cells because you can determine which material would be best for a solar cell.

For the second lecture, he discussed femtosecond spectroscopy, pump-probe spectroscopy, and Terahertz imaging. A femtosecond is 10 -15 seconds. To be able to create faster electronics, you need to analyze at a smaller length scale. The combination of optics and electronics can lead to new high speed devices, and this is why terahertz technology is a hot topic. Dr. Stanton’s lectures were most helpful when he introduced the applications for the solid state physics concepts we were learning about. By tying what we were learning with LEDs and solar cells, I have more interest in research. Sometimes I feel like research is running in circles, but with the kinds of applications Dr. Stanton introduced, I am able to see the purpose for all of the detailed research that sometimes appears to be aimless.

Otsuji-sensei covered Terahertz basics and applications. He also quickly covered band gaps and made the relationship that the curvature of a band gap plot is the mass. The cool thing about terahertz rays is that it can see hidden substances. Terahertz rays shine on a substance, and different consistencies of the object absorb terahertz radiation in different ways. He showed examples like a business card in an envelope that could be seen through terahertz radiation because the black ink of the card absorbs terahertz radiation differently than the white paper. The same can be done with a fresh leaf versus a dehydrated leaf—you can see what the water distribution is in the leaf. The terahertz regime is between microwaves and infrared waves. The wavelengths are longer than the visible spectrum. Terahertz radiation could apply to electronics, because if you increase the capacity of the carrier frequency, you can download things a lot more quickly. If you use terahertz radiation, you could send more information through its wavelength. Otsuji also included many analogies to help us understand physics concepts. For example, you can estimate how many electrons are in a semiconductor by thinking about stadium seating. To estimate the number of people in the stadium, you should try to estimate: How many seats exist? What is the probability that someone will be sitting in the seat? Otsuji also likened pumping electrons to a game of Pachinko. His lecture ended on an optimistic note as he believes that the dream of graphene terahertz lasers will exist in the future.

Otsuji-sensei’s lecture continued to show application for terahertz technologies. It was pretty cool to see that you could detect what a business card said even when in its envelope. I’m kind of paranoid about X-rays and TSA scanners, so seeing that safer methods are being developed makes me feel better.

My first day of lab was an enjoyable one. I was pretty self-conscious in my sweat-soaked formal outfit walking around meeting everyone, but every single person I met was friendly and really made an effort to reach out and talk to me. I do not feel a sense of hierarchy in the lab, but that may be because I have either been sitting in the student offices socializing with the grad students, or in the lab being taught by Kumiko-san or Kuma-san. I call the professors by –sensei, and the graduate students by –san. A few graduate students have told me that I don’t have to call them by –san, which is nice because I sometimes forget anyway.

My main mentors right now are Kumiko and Kumamoto-san. Kumiko is a calm, patient graduate student who has been teaching me the process of transfection. Kuma-san is a post-doc. He is extremely kind and understanding, and the master of DUV spectroscopy. Even though he is so accomplished, he is not intimidating; the first day I worked under him, he wore a Kuma-mon polo because of his name. The next day, he wore an identical polo with a different bear in the corner. The other members of the lab are very outgoing and a giggly bunch. It’s true that Osaka people are funny; they all are happy and laughing at each other. They like to socialize, which is nice because they really make it easy for me to talk to them.

English is officially the language of which this lab is conducted. Everyone is able to speak English to some degree, although some people’s English is still pretty broken. I sat in on a paper review where graduate students give a presentation on a paper they studied and what they thought about it; sometimes it would be hard to understand their explanations, and when Kawata-sensei pointed out flaws in their presentation material, they were unable to defend themselves very well in a second language. Jordan (previous NJ student) told me that this was one of the most international labs, out of all of the NJ placements, so I was expecting everyone to be very comfortable with English. However, I have met a lot of lab members where it is easier for me to speak Japanese to them when they don’t understand my question in English. What was interesting is that people were so surprised when I spoke Japanese to them. I am so used to people expecting more from me than I can deliver, so it was a nice change of pace for people to have no expectations because I am American, and then show them how much effort I put into learning Japanese to communicate with them. I think my ability to speak will help me get my point across so there will be less miscommunication. I am still unsure whether they like to speak in English to me or if it’s alright if we speak in Japanese, because I really want to practice Japanese while I am here.

My housing is a very humble dormitory an hour away from the lab. I have the choice of either commuting by bike, or by walking and riding a train. I want to travel by bike, but because of my sickness I’ve been trying to conserve energy by riding the train and walking. The room I have is the same size as the Sanuki Club’s, but at least I have a fridge. Some shared spaces of the dorm are in disrepair; you can tell that it’s very old and it’s very much a group effort to keep it in good condition. The bathroom and shower is fairly clean, but the kitchen is nightmarish. Maybe I’m getting used to Japanese standards of clean, because the appliances are all splashed with mystery food that’s been baked on for ages. The garbage can is overflowing with moist food scraps, and I’m not sure if the residents take it out or some cleaning person comes (I’m thinking it’s up to us to get it out of the kitchen). I think this will force me to explore Osaka for food, which is a good compromise as I heard Osaka is known for its cheap, delicious food. The people here are extremely nice and interesting as they approach me and ask about where I’m from, but with my sickness (from a bad cold) and general tiredness I haven’t made a strong effort to meet them.

I have begun practicing the techniques necessary for my research project. I will be using DUV spectroscopy to measure the optical properties of native proteins in cells, and as a separate case, measure the optical properties of injected proteins in cells such as fluorescent proteins. I will then evaluate the effectiveness of using the combination of DUV spectroscopy and fluorescent protein to visualize the cell. The only worrisome thing about this project is that deep UV light has such a short wavelength that it’s invisible to our eyes but causes deep burns. Kumamoto-san is helping me out whenever I use the lasers though, so I think I should be fine.

The first week in lab was a good one. Everyone is so open and friendly, and I feel like I can walk up to any of them and start a conversation. They all have a great sense of humor, so it’s funny to see their perspective on things like what they want to do in their future or why they even chose Handai. I found myself walking home yesterday with the problem of a sore mouth from smiling all day. I just hope that I don’t cross that line where I stop being too serious and my research or my reputation suffers. Although my experience in lab thus far has been enjoyable, I’ve been staying in the dorms for the past two days because of a very strong cold that I contracted before leaving Tokyo.

Pro-tip: TAKE CARE OF YOURSELF. Don’t feel like you have to see everything/ do everything during the first three weeks to the point where you’re exhausted and not sleeping enough. Health is most important. Otherwise you will be sick during your first week at your research lab like me!

I have a desk next to Kumiko!

Research Project Overview

My project is about visualizing proteins of a cell. I will visualize either the natural fluorescence of native proteins in cells, or fluorescent proteins that I transfect into the cell. Thus, I will study the optical properties of the fluorescent proteins and the native proteins, and evaluate the quality of resolution from the spectrometer. Both deep UV spectroscopy and the use of fluorescent proteins have been techniques for visualizing cells, but the combination of using both has not been studied. The goal is to figure out how effective the combination is for imaging purposes.

Research Methods: First, I will have to make the cell samples of which I will be observing using DUV spectroscopy. This requires the usual wet lab tools like pipettes, petri dishes, cell counters, and incubators. I will also be using DUV spectroscopy to measure the fluorescence of my samples, so that means messing with a laser and its mirrors and using a computer to measure fluorescence of the sample.

Training: Kumiko is training me on how to prepare the cell samples and GFP/RFP/YFP samples, and how to transfect the cell with the fluorescent proteins. Kuma-san is teaching me how to align the laser for DUV spectroscopy, and then how to take DUV spectroscopy measurements. He is also teaching me how to read he spectroscopy measurement data. By learning from Kumiko and Kuma-san, I will be able to make cell samples with or without fluorescent proteins, and then I will be able to measure the fluorescence using DUV spectroscopy. I can then determine how well the resolution is from using fluorescent proteins and DUV spectroscopy.

Timeline: Kuma-san told me that he wants me to complete these things before leaving for Okinawa (for the Mid-Program Meeting)

This is what I got out of the two days I was in lab. On the other days, I stayed back at the dorms to recover from the bad cold I got in Tokyo. Although I feel better, I feel a bit behind on what I need to accomplish for this project. I think I will spend at least one day each weekend to rest and recover in Osaka so I can make sure my project is going at the pace it needs to complete it before the symposiums.

My lab mates have all been extremely welcoming and inclusive since I’ve arrived, and since they’re pretty outgoing they ask me questions about my unconventional American upbringing. The two questions it seems everyone I meet in Japan asks:

It’s interesting that food is a recurring question, because it’s something really random about my life that I never thought would be interesting, and it’s always hard to answer. Somehow, even though my mom made Japanese food, I was very particular about which meals I liked and which meals I didn’t. The term “acquired taste” seems like a hoax to me, because being fed certain Japanese dishes as a child didn’t stop me from hating it as an adult. Thus, my answer to popular question #2 is usually accompanied with thoughts of foods I like, and the foods I don’t like in Japanese cuisine. For the beginning of the program, I answered the question about food with a kind of filter; I always just said, “yes my mom cooks Japanese food,” not wanting to expose myself as “not being Japanese” by admitting my dislike for traditional Japanese food. My parents instilled a kind of embarrassment in me for my eating habits, as they would always have some frustration and disappointment when I refused to eat certain dishes when I was younger. As a result, I’ve kept my dislike for Japanese food a secret for most of my life in fear that more people would be disappointed in me for not being “Japanese”. But after I’ve heard the question about food so many times since arriving in Japan, I’ve become more comfortable talking about it. By the time I got to Osaka, I had the details worked out and well-rehearsed; I don’t actually like traditional Japanese food, and it became easier to say that out loud.

One day I was sitting in the student offices and the question came up again. I answered with complete honesty, “I like tempura, korokke, gyoza, easy Japanese food like that. I don’t like octopus, squid, most fish, soy sauce flavor,… every meal in Japan has a distinct Japanese taste that I don’t really like.”

Maru-san looked at me like I was crazy. “You’re a child!” he says incredulously. Okuno-san mutters in Japanese, “it’s because you’ve never eaten anything delicious in your life…” I just continued to smile awkwardly and laugh it off, as my mother would say the exact same things. The awkwardness dissipated when the topic changed to something else.

This event was significant because I’ve heard these kinds of comments when I was little when I refused to eat some of the more Japanese meals my mom would make. Whenever I heard these comments, I knew I was embarrassing myself in front of my parents. Was I embarrassing myself in front of my labmates already?

For me, my answer had good intentions. I wanted to be honest! However, I did not anticipate the kind of negative surprise from my labmates. Usually people go, “ehhh?” in surprise and then leave it at that. My labmates’ comments kind of made me take a step back, because I heard my parents embodied in their comment—the disappointment and slight frustration tinged in their words.

And even though it hurt a little for my labmates to roast me for my eating habits, my labmates had no bad intentions with their comments. They made valid, funny comments that only come out when you feel comfortable with the other person—almost a compliment! The reason why it didn’t feel like a harmless comment was because it was like an old echo from the past with my disappointed parents behind it.

This was a kind of misunderstanding in my head, not really a confrontation with my labmates. Thus, I just held in my feelings of embarrassment and shame, smiled and changed the topic of the conversation. Next time, I need to realize that I am who I am, and I need to stop worrying about what others think about me so much. I shouldn’t feel embarrassed about my eating preferences! At the same time, I should be more Japanese in the sense that I should choose more indirect phrasing when describing what I think about Japanese food, instead of outright saying that I dislike it.

Eating yakiniku with my Liang-da san and Wataru san. The lab makes fun of me for my obsession with beef.

Research Project Update

I think most of my confusion has been ironed out; I will be studying the effects of fluorescent protein under DUV excitation. DUV excitation has not been explored because it’s easier, simpler, and proven that you can analyze fluorescent proteins using visible light. However, DUV light has the advantage that it excites all of the fluorescent proteins and dyes used to analyze cells; you are able to collect more information with one measurement, instead of measuring multiple wavelengths in the visible spectrum to excite all of the fluorescent proteins you used. Kumiko showed this to me in a measurement; we went to perform ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (at least this is what I think we did; I tried to figure out the name of the process by Google and this looked like what I did. I need to remember to ask Kumiko whenever I perform new experiments!)

We put in each fluorescent protein sample in a rectangular prism, which we inserted into a machine. The machine collected data of excitation vs. wavelength, and graphed it. After analyzing GFP, RFP, and YFP, I saw that all three samples had high excitation at 266 nm—the DUV wavelength I am using to excite fluorescent proteins in my project. It finally made sense to me to see this graph to realize what Fujita-sensei meant whenever he said that DUV excites all fluorescent proteins and this is how we will extract the most information with only one measurement.

This week, I was able to practice the transfection of GFP, RFP, and YFP into my cell culture. However, when Kumiko and I checked to see if the process was successful, we could not find cells to analyze to see if the process worked. Thus, we concluded that I will have to re-make the samples with a higher number of cells in each sample so I will be able to actually determine whether transfection was successful or not.

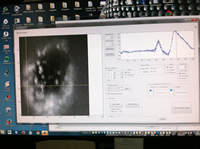

On the DUV front, I learned how to process the data from the machine. It takes a lot of effort to make one measurement. First, you must make sure the laser is at the correct intensity; we must account for how little is actually reflected into the sample by delivering a higher intensity. Then you have to find the cell you want to image, focus the microscope, input the dimensions you want to scan, position the sample so you scan a cell, input step size, input exposure time, and then start the measurement. The most tedious part of the process is a tie between focusing and refocusing the microscope and laser, and reading the data to generate an image. In order to read the data, we have to convert the data into many different formats, apply SVD through Octave, and run the data through Igor. It’s a homemade method produced by Kuma-san, and although it’s effective, I am very slow at it since it requires a lot of steps. Kuma-san saw me struggle with it, and has instead come up with a process where all it takes is MATLAB, and going to the computer in the student offices to analyze the data using a MATLAB software. It’s very rewarding to see the image of a cell appear on the computer, and I am starting to understand the meaning behind how the images were taken. However, I am still confused by the simple measurement we always do: the spectrum of each pixel. When I put a cursor down on a pixel of the image of a cell, a corresponding graph appears that shows me the spectrum of that pixel snapshot. I don’t understand why there’s a spectrum associated with each snapshot; won’t the measured light coming from the sample be just one wavelength instead of a spectrum? I’m just imagining that we are shooting one wavelength of light into the sample (DUV light), and then one wavelength of visible light comes out of the sample to be measured. I feel like this concept is really easy to understand, but I’m just not getting it.

So far, the difficulties have been transfecting my cells properly and getting used to using the software to image my collected data, and understanding completely how to interpret my data. Kuma-san told me I will soon have to define my research question, but when I gave him some questions I was thinking about (will repeated DUV spectroscopy alter the sample, will a longer exposure time with less laser intensity give better results than shorter exposure time with more laser intensity, etc) he responded that these are all unknown and we will have to do more experiments to find out. He then told me I won’t have to come up with a question right at this moment, so I think what’s going to happen is that I will become more familiar with the properties of DUV spectroscopy and its effects on a cell, and THEN I will come up with a more in depth research question.

During the last bio-meeting I delivered a powerpoint presentation about my project, which has the purpose of letting Fujita-sensei and Nick-sensei and other researchers know the progress of the research projects for different Masters/PhD student. During the Q/A session, I learned a lot about what I don’t know about my project, which was embarrassing to do in front of all of the senseis, but they were all very relaxed and supportive which really eased my anxiety.

The Kawata lab is relaxed and has a number of international students and women, and as a result I would say it’s not the typical Japanese lab experience. Honorifics are based case-by-case; I mostly interact with second year graduate students, and they call each other by –chan, -kun, and –san. –Chan is reserved for the adorably giggly student Kana, -kun is reserved for people like the goofy male student Sekiya, and –san is used for the majority of the students. Last names are generally used, but first names are used for the very outgoing, smiley type of person. Basically, if you feel comfortable with them and you implicitly know they won’t mind, I think they use –chan and –kun. I’ve noticed that disagreements are settled very directly, but there’s still a lot of respect shown between both people. Whenever Kuma-san corrects me it’s always very direct. I think this is because he instructs me in English, and English is a very direct language. In Japanese, there is no equivalent of “no” in Japanese polite mode (a mode reserved for professors or superiors), so it’s actually impossible to find words to refuse them. In English, Kuma-san is able to tell me “don’t do this, don’t do that” which comes off as very direct in comparison to what I expected.

This experience is different from what my NanoJapan alumni mentor had, which is interesting. Jordan told me he wasn’t allowed to call Kana “Kana-chan”, and instead had to call her “Kobayashi-san”. The stark contrast of both using her last name and a more respectful honorific was interesting, as she actually corrected Jordan to call her that. Maybe it’s because I am female that she lets me call her Kana-chan. Professor Kono told me this lab was very welcoming and easygoing, which was true. The hierarchy is present in the form of politeness toward senseis and older grad students, but it isn’t very strict and people do not get offended.

In terms of academic research, I feel that the US is much more interested in seeing results than Japan. I talked to Shota about what he felt when he studied at Rice during 2011 Reverse NanoJapan, and he said that Americans seemed to show off their results more, and basically make it very public that they think they work is number one. I do not perceive a difference in how hard Japanese researchers work, as they work the hours they need to complete their experiments in time for the next meeting or presentation just like an American grad student.

Also, the lab size is much bigger in Japan. There are 35 students in just the Kawata lab, and as a result the professor is not very present for one-on-one guidance. Instead, I feel like the lab interacts with post-docs and each other for guidance. The assistant professors are much more present in the lab, as they attend bi-monthly presentations of the graduate students’ progress, and then give opinions on their next steps. The namesake of the lab is just too busy to give in depth guidance, and as a result you grow very close to your labmates, post docs, and the assistant professors. One day Kawata-sensei ran into the student offices, barraged the older graduate students with questions on their progress, saw me while walking out, stayed less than a minute to ask how I was doing, then decisively ended the conversation with “okay I have another meeting” and rushed out the door. Of course, it’s not that Kawata-sensei does not want to talk to you, it’s that he is literally booked for the entire day going from meeting to meeting. It was almost comical how it played out, but that’s the reality of this lab; no time to talk to the main professor, but finding ample guidance from those around you.

I don’t have much experience seeing a lab culture through an American standpoint, because I worked under a Chinese international graduate student in the US. If I had to choose, though, I would say that I enjoy Japanese lab life more, because there’s a lot more people to interact with and get more feedback from. There’s always someone in the student offices working on a PowerPoint or paper, so if you need any help you don’t have to go searching far for the wandering professor. Also, it’s really awesome to go out as a group for dinner or other fun events; even the casual “hey, wanna go to the konbini to get some food?” brings me a lot of happiness. This feeling of belonging is conducive to the “team” mentality that I thoroughly appreciate.

I can be as awkward as this fish and still feel welcomed in lab! Taken at Osaka Kaiyukan

Research Project Update

This week, I analyzed my DUV data taken from HeLa cells without any transfected FP. I compared many spectra against each other to see how certain factors affect the sample. For example, I plotted the spectrum of a cell at one specific coordinate (in red), and the spectrum I took later of that same cell at that specific coordinate (black). You can see that the DUV irradiance has an influence on the data, as the second time I took an image, the identical location now has more fluorescence. This might be from the effects of DUV irradiance; the DUV light has altered the cell so it gives a higher signal than originally. From these plots, I can conclude that exposure to DUV light alters the cell, and so I need to image a new cell every time I use DUV light. I also concluded that time also affects the fluorescence of a sample, so I need to use a fresh sample every time I take an image.

This week I also successfully transfected HeLa cells with fluorescent protein. I made 7 samples: 2 RFP, 2 GFP, 2 YFP, and 1 non-transfected cell sample. To check for successful transfection, you shine visible light into the samples and look for glowing cells through a microscope. It was really exciting to see my FP-infected cells, not only because they were in fun colors but also because this week I became more independent and more comfortable with the process of transfection, and the success was measured by a great image through the microscope.

Now that my samples were made, Kuma-san helped me image these cells through the DUV spectrometer. Because DUV light is relatively underutilized and unknown, we had a lot of problems pop up when we were taking images. When we started imaging and saw that the collected spectra at each step size had no signal, we had to stop and increase the laser intensity as we were not exciting the cell or the FP. Then, when we took an image again, the spectrum was one huge, rounded peak. This was bad because the DUV was exciting the native proteins in the cell, and as a result the FP signal was overwhelmed by the signal from the native proteins. Thus, we couldn’t see the specific structures that the FP were going to indicate because the specific wavelength peak we were looking for was engulfed in the one massive, wide peak. To fix this problem, we lowered the intensity of the laser. We also decreased the exposure time from 0.1 seconds to 0.05 seconds because the laser intensity was still very strong and so it has the potential to alter the proteins in the sample if exposed for too long at that strong laser intensity. When we took another image once more, the result was a striped image that faded to black at the end of every stripe. This was from the fluctuation of the laser intensity. Laser intensity can fluctuate with a change in temperature, so Kuma-san tried to make the air temperature constant to prevent this fluctuation. For our next measurement, we ran into the problem of an irregular exposure time. We remedied this by lessening the laser intensity, because through Kuma-san’s experience, it would lessen this problem.

Also, when we measured YFP, it was too difficult to find its signal so we changed my research goal to analyzing GFP in a cell sample, RFP in a cell sample, both GFP and RFP in one cell sample, and a non-transfected cell for comparison. With each measurement taking about 2 hours to complete, all of these problems that plagued us were time consuming and gave us poor results. However, with more cell samples and trial-and-error, I think we will find the best values to work with for time exposure, step size, laser intensity, etc. to be able to see better results.

On Monday, I plan to culture more cell samples at 10:30am so I can finish in time for the NanoJapan visit, and on Tuesday I plan on transfecting the cells.

My biggest accomplishment so far during the NanoJapan Program was realized when I was in the worst of moods. It started with the end of the day at lab a week ago. Lately I’ve found that the most difficult part of the day is leaving lab. I love seeing my labmates everyday and learning from Kuma-san and Kumiko, so when the sun falls and the thought of walking home super late at night threatens me, I have to force myself to leave laSIE and make the trek home. Since there aren’t many people walking outside that late, generally I’m the only one on the sidewalk with the occasional scooter or car breaking the silence when they whizz by. As a result, I’m usually lost in my thoughts so my brain can make the monotonous walk bearable. That night, my head was mumbling a laundry list of complaints, from my disappointing day of failed results to the rocks in my shoe that I refused to stop and dig out. I was pretty miserable, but suddenly on my way up the hill, I realized something that I didn’t even notice. That inner voice in my head was complaining in Japanese. And then I stopped and tried to remember what I was saying specifically. How did I remember those words? It was a kind of the first moment I seriously reflected on how my Japanese has improved since getting here. I have noticed that my vocabulary has increased and I can speak Japanese without thinking too hard now, but at that moment walking up that hill while complaining in my head, I was naturally thinking in Japanese.

During the Tokyo language classes, I always felt that I was always thinking for the right words, meticulously scouring my mind for the correct sounds. But midway through the program, my brain is now rewired to think in Japanese naturally. Of course I haven’t reached the fluency I had when I was younger, but it’s amazing how the brain can hold a bank of knowledge you haven’t touched for more than ten years, and still retain it. I have been amazed by the words coming out of my mouth lately, because it’s nothing from what I learned in the language classes. It’s words that I can hear in my head, and my mouth clumsily says it out loud until it sounds like what’s in my head. When I learned Spanish in high school, I would have to proactively think out my sentence, and translate sections of it into Spanish in my head. I would pull out vocabulary words I learned from the week, conjugate the verb I chose from the bank I have in my memory, and say it. Relearning a lost language is completely different; I have a kind of feeling or mood associated with a word or phrase, and when the conversation triggers my brain to have that feeling, it is able to find the right sound to match it. To have my brain be able to complain and argue with itself in Japanese is downright impressive for me, and I think that’s the biggest personal accomplishment I’ve had so far during this program.

My biggest personal challenge is getting over my overcritical self. I constantly beat myself up for not understanding my project, and it’s a hindrance to my productivity. A lack of confidence causes me to lose my direction and focus wading through my data, and I end up overwhelmed by what I need to accomplish. I feel like taking a step back, writing down what I need to do, and doing it will ease the stress and help me see the bigger picture.

My research is progressing, but I have been told I also have to present on my NanoJapan experience and what it means to me to be an international researcher. Thus, I need to make sure I do not neglect my reflections of what I am noticing and how I am growing as a person. My main issue for my research is understanding what the data I am collecting means, and how I am receiving that data. This was a big concern for me going into the program, because I feel like I learn slower than the average person. The only issue with my research is the tight timeline and my ability to be productive at the pace NanoJapan pushes us to be at. A more practical issue with my project is the laser intensity fluctuation. The laser we use to shine DUV light on the cell samples is very sensitive to temperature. A fluctuation results in a DUV image with sections that fade to black where there should be a signal. Right now we are brainstorming ways we can fix this problem, all revolving around how to keep the temperature in the room constant.

The katorisenko (mosquito coil) smell reminds me of my childhood when I visited Obaachan!

Research Project Update

For this week, I transfected more cell samples for DUV imaging. I made one sample with GFP, one sample with RFP, and one sample with both GFP and RFP. I also made one sample without any transfected fluorescent proteins, as I wanted a comparison between a nontransfected cell and a transfected cell. I am now imaging the sample with GFP and RFP with Kuma-san.

After Sarah’s, Packard-sensei’s, and Kono-sensei’s meeting, I felt like I really didn’t know my project well enough. I debriefed with Kuma-san on how to make a better presentation and how to explain my results better. I need to spend more time on understanding the purpose of each slide, and how I want to prove the point I want to make. The data is my evidence for any claims I make, and I need to be convincing. Thus, I need to make sure my evidence is presented clearly, and in a straightforward manner. So far, I have so much data that I am overwhelmed with what claims I can make with which data. I need to take a step back and think about what I want to say, and how my data reflects my claim. I will continue asking Kuma-san if my understanding is correct, and ask him to elaborate on the parts where I am still confused. The difficulty/setback this week is my understanding of my project, so I will be working hard to understand my project’s data, and make sure I can organize my data to present it well.

Learning Japanese has been one of the most fascinating experiences I’ve had. I would say that at this point in time, I’ve been progressing toward conversational level. It’s a lot more natural to speak what’s on my mind, and it’s not uncomfortable anymore to scour my mind for the right words. The fascinating part about my progression in Japanese is that I haven’t been studying new words; my brain has been recalling everything that has brought me to conversational Japanese level. As I continue to practice speaking with my labmates, I’ve been surprised with the vocabulary that my mind has remembered. From obscure verbs like lining up at a cash register to phrases like “kamo shirenai” when I’m kind of not 100% sure, my mind has been brushing off the dust from my first language. The downside to this is that I have a hard time remembering new phrases and words, and I’m not very good at making complex verb tenses. I don’t even know how to string together a grammatically correct sentence. However, my patient and forgiving labmates are very good at deciphering my baby talk and the conversation can continue smoothly. The good side is that the finite bank of language knowledge can be accessed fairly quickly and naturally so I don’t spend time thinking too hard. To continue studying Japanese, I feel that I just need to keep practicing speaking it out loud, and continue to hear my labmates insert new vocabulary in the conversation that I can pick up.

My most challenging linguistic experience thus far has been speaking to my grandmother. My labmates are very good at speaking with vocabulary that encompasses everyday common things that I know, but my grandma uses vocabulary I’ve never heard before. This may not pose a problem to most people, but for me I get really nervous and panicked when I don’t understand my grandma when she’s speaking to me. When she asks me a question I don’t understand, I feel like I have to respond in a timely manner or I’ll disappoint her. I usually only ask once for a repeat before I freak out and find my dad to help translate. Even though my grandma is a very patient person given her age, I still feel that uneasiness or fear sitting with her while I anticipate a conversation that I don’t understand. I think what keeps me from being comfortable with my grandma is the context of the situation. At Handai, I am the American girl who is working hard on learning a second language; my efforts are appreciated when I try to practice with my labmates, and the fact that I’m trying makes up for my poor Japanese. With my family, I am the Japanese girl who can’t speak with her own grandmother; my efforts are overshadowed by the fact that I threw away my heritage that I should have been proud of, and the fact that I’m trying to practice does not erase the fact that my ties to Japanese culture has deteriorated to almost nothing. Even though I progressed so far in learning Japanese, I still find myself struggling to communicate with my grandma which is kind of hard to bear.

Through this experience, I learned it is possible for me to be comfortable practicing Japanese—I just never had the opportunity to do it in a less judgmental, self-conscious environment. I feel that this experience has taught me that communication is more than just getting your point across; it’s an expression of who you are by the words and tone you use, and I feel that although I’ve reached a satisfying level of conversational Japanese with my labmates, I am still painfully far from where I want to be when speaking with my family.

The most effective techniques for studying Japanese is being a good listener. If you listen to your labmates talk, you’ll get used to the initial barrage of foreign words and you’ll start picking up on what you know. Then you’ll make context connections so you understand the topic they’re talking about. Soon you’ll develop certain scenarios where they use certain phrases, and at that point your brain will be able to pull out that phrase naturally when you “feel” that certain scenario.

My experience in Japan has made me want to continue studying Japanese. Speaking with my labmates is fun, but I want to keep learning and improving my Japanese for my grandma. I feel like I have been absent from her life for too long, and seeing her in Kyoto after so many years, I am realizing how quickly she is aging. I want to make up for all of the lost time, but to do so I need to put in the effort of learning Japanese.

For continuing Japanese, I am not sure what I want to do. The problem with language classes is that I am a weird case where I have knowledge gaps in sentence structure that would hinder my ability to skip levels of a language class, but I have the vocabulary bank greater than a beginner. I took Japanese for a few days at Rice before I got bored from the constant “repeat after me” and dropped it, so having a rigid class agenda is not very appealing to me. I could go back to Kumon as that was what I was doing in 5th grade, but it’s expensive. In the end, the dark cloud looming over all of my plans are my engineering courses. I need to gauge how manageable my schoolwork is first to determine how much I can allot to Japanese study during the school year.

The Mid-Program Meeting was a much-needed reunion between all of the NanoJapaners. The most helpful part of the meeting was dissipating the fears and anxiety I had about my project. I felt very reliant on my mentor, and to hear that Lauren also felt that way made me feel better. During the orientation, I felt like I was the last one of the group to understand any of the topics covered in the lectures, and I was very worried that I would be the problem child of the research portion. The fact that I feel like a research assistant to my post doc mentor made me less confident in my abilities as a researcher. However, hearing that other people felt the same way made me realize that feeling that way is normal and is just the reality of the kind of work we do. We are playing around with such expensive equipment and the process of using it is so complicated that we just can’t afford to do it ourselves with such a limited time frame. My plans for the rest of the summer are to calm down and work hard for this last stretch before delivering the final product. I have such high hopes for my poster and presentation but I have to push to get there.

Nicole and I went to Hiroshima for a lesson in history about August 6, 1945.

Shota is ready for his speech for the master’s students!

The lab is always ready to help each other out!

Research Update

Once I got back from Okinawa, I have been transfecting more cell samples so I can measure their signals using DUV excitation. This week’s batch consists of 2 samples with both RFP (which indicates the cells’ mitochondria) and GFP (which indicates golgi), 1 sample with CFP (which indicates the cells’ nucleosome), 1 sample with YFP (which indicates the cells’ actin), and 1 sample with mCherry (which indicates the cells’ mitochondria). Transfection was successful for the RFP and GFP sample, but I could not find transfected cells in the other samples.

The trouble with the sample with both GFP and RFP in it was the quality of transfection for RFP. The GFP-transfected cells were very easy to find (using band pass filters that selectively allows only the excitation wavelength to the sample), but when we checked these cells for RFP, we couldn’t find many cells with a signal. Thus, when we imaged the cells using DUV excitation, we were unable to visualize the RFP because it didn’t provide a signal. To remedy this problem, Kumiko will help me make more batches of transfected cells. I think the technique for transfection is what is causing these problems, and having someone more experienced perform transfection will be better.

Another problem we’ve been having is that autofluorescence is overwhelming the signal from the fluorescent proteins; it is very difficult to unmix what wavelength is contributed from the FP versus the natural fluorescence of the cell. Thus, it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly where the golgi bodies, mitochondria, etc are in a cell since we’ve been getting one wide peak that encompasses the emission wavelengths of the FP. To remedy this issue, we have lowered laser intensity to 3.9 uW. When imaging with this new laser intensity, we generated an image with distinct emission wavelengths from the FP. The laser intensity was low enough that autofluorescence did not overwhelm the FP signal! We have finally found good conditions to image FP in cells using DUV excitation: 300 nm step size of a 30um x 30um area, exposure time of 0.1 seconds, and a laser intensity of 3.8-3.9uW.

For next week, we will be making 1 sample transfected with GFP, 1 with RFP, 1 with TFP, 1 with Sirius, and 1 that is triple-transfected with GFP, RFP, and CFP. The tricky thing about TFP is that it’s emission wavelength overlaps with autofluorescence. It will be difficult to distinguish what is TFP and what is just the cell fluorescing from DUV excitation. To recap, GFP stains golgi bodies, RFP stains mitochondria, TFP stains nucleosomes, and Kuma-san said it doesn’t matter what Sirius stains this time around ,we’ll just play around with it so what it indicates in a cell is to be determined.

Haruko Obokata was a young, up-and-coming female scientist with a lot of potential. She was skyrocketing upward in her biochemistry research career, and the media loved her because of her unconventionality as a scientist: female, cute, and with a personality. The Japanese science institute RIKEN hired her, and there she published a controversial paper about STAP (stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency) cells; Obokata claimed that she was able to induce regular cells into pluripotent stem cells, which is big news in the science community. Pluripotent stem cells can become any type of cell, which can be the solution for a number of degenerative diseases. Her claims were high, as her papers stated a way to create such an amazing cell using easy, simple methods. The media went wild. The hype gathered suspicions, and soon the miracle was shattered; a lab group at UC Davis could not reproduce the same results. Now the media picked up the momentum, and now Obokata’s work was under intense scrutiny; her papers were now under fire for plagiarism, doctored images, and incorrect data. Her quick rise to stardom suddenly came crashing down as she had to explain these discrepancies to the world. At the same time, the mass media parasitically fed from her situation and blew her story to astronomical proportions. She apologized on TV, but steadfastly continues to stand by her research. Currently, RIKEN has given her a lab for her to reproduce her work. It is under careful surveillance from cameras and the world watches to see if her research was truthful or not.

The most important issues affecting this controversy are: 1) the power of mass media and 2) the state of academia today. I myself had not heard of this controversy until arriving in Japan, but when I asked my grandmother about it, she was well-versed in the story and ready to discuss it. If an elderly lady with no internet access and very little interaction in town has an opinion on this scientist, I believe the media in Japan has been overzealous with its reporting. Talking with my labmates, they were all sickened by the kind of treatment Obokata has received by the media. Many of my labmates said that it doesn’t really affect them or their interests, and so they felt that the story was like an overplayed pop song. No one’s career should be treated like that especially for a scientist, and so I feel that although this is one of the biggest scandals in the history of research, Obokata’s situation was blown out of proportion, with unnecessary emphasis on her being a failed female scientist role model for all young girls. The second important issue, the state of academia, is reflected in this scandal. There are too many PhDs granted for the number of positions open in academia, and so there is so much pressure to be the best. Also, according to one of my labmates, academia these days is dependent on fulfilling your supervisor’s expectations. This brings about an “ends justify the means” attitude toward research. This can lead to a lot of cutting corners like what happened in Obokata’s papers.

In this case, I think the main factor that influenced these issues was the pressure to publish research. One of my labmates chronicled the fact that Obokata’s research/publishing history was not as developed as it should have been to be granted a job at RIKEN. However, RIKEN was very impressed with her research proposal of STAP cells, and accepted her. Word has it that she didn’t even have an interview. This pressure to deliver on the topic that got her into RIKEN might have influenced her to publish quickly to save her job. Another interesting fact is that RIKEN has not produced any Nobel prize winners. Kyodai (Kyoto University), Todai (University of Tokyo), and other Japanese institutions have that recognition, but the most government-funded institution, RIKEN, has yet to hold a winner. This increased pressure can push researchers to questionable practices to get results. I don’t think prestige was a factor. Pressure to perform at the expectations of RIKEN probably pushed Obokata to the brink.

My reaction is that I don’t think she is a crook or a fake, but just a victim of the circumstances. She publicly apologized but is still standing by her idea. I think it was good for RIKEN to give her a chance to prove herself, because it’s fair that if she claims that it’s true, she should be able to show it to everyone. I think there is blame for RIKEN for hyping up this monumental discovery and putting more pressure on Obokata, and I also blame the media for treating her mistake as a circus show. I feel like the exposure she got on the media was equal to or worse than a celebrity’s. My labmates feel the no extreme emotions; they see problems with RIKEN, and they know the pressure of being a researcher. Overwhelmingly, all are disgusted by Japanese media and their exploitation and twisting of stories as propaganda against the cute rikejo that fell from grace.

Week 09 Research Snapshots!

Research Update

I presented a research update to Fujita-sensei and Kuma-san. After presenting the information, they questioned the viability of getting a GFP excitation that can be separated from autofluorescence because it is too small to differentiate from the strong autofluorescence signal. Fujita-sensei pointed out that we were probably not getting a high signal from GFP because we were using an excitation wavelength of 257nm. He showed me a graph that showed that all FPs have a high peak at 280nm, so Fujita-sensei wanted me to use 280nm to excite my samples for higher emission signals. However, laSIE does not own a laser with that wavelength, so we will be working with the next best laser wavelength that we do own, 266nm. If we have time, Fujita-sensei recommended that I try wide field microscopy to perform analysis with 280nm excitation. Sirius and CFP have a very strong signal with 280nm excitation, so I will be transfecting cells with these FPs next. I think the biggest limiting factor at this point, besides the dwindling time, is the luck involved with transfection. I hope to include results from CFP and Sirius on my poster, but that can only happen if I can create samples with CFP and Sirius in them.

Kumiko made a sample of CFP/RFP/GFP-transfected cells, so I will be processing that data when I can have access to IGOR. Another factor hindering my progress is finding a way to use IGOR. My free trial ended this week.

A number of women are members of laSIE, and so I had no trouble finding female researchers to talk to. I met up with Kozue, Kana, Kumiko, and Mai to chat about their decision to pursue research. They are all applied physics majors, and they decided to study it because, simply, they find the subject interesting. The general consensus from our conversation was that it seemed that undergraduates in Japan have a lot more free time than the undergraduates of the US. I found it interesting the way they said it: “it’s difficult to get into the top universities in Japan, but it’s easy to graduate. It’s easier to get into the top universities in the US, but it’s difficult to graduate.” I asked whether they’d rather have the “US version” of university culture of getting accepted and then working hard to earn your degree, and they all agreed that they would rather stick with the Japanese way of having fun for undergraduate life. I can’t blame them; sometimes I wish that the US operated in that way, but to think that one test can determine your academic future in Japan is also stressful. They said that graduate school is pretty busy though, which seems equivalent to the US. All want to work in industry after their degree.

Kana, Kumiko, and Mai are working on their master’s degree, and Kozue is working for her PhD. Kozue is constantly encouraged by Kawata sensei to join academia, but Kozue is sure she wants to work in industry. She says that she decided to work for a PhD as a requirement for the job she aspires to have. Kana is getting a master’s because she likes research enough to continue it for a couple years, but she doesn’t have the money to continue toward a PhD and so she is aiming for industry after receiving a master’s. Kumiko wanted to pursue a master’s because she didn’t feel like working straight out of undergraduate life and it’ll keep her competitive for a job when she receives it. It seems that Japanese students don’t have grandiose dreams like US students; everyone seems very realistic about their future by thinking about getting a job so they don’t accrue more debt by pursuing what they truly want (getting a PhD), whereas US students follow their dreams, get into debt, and complain about how unfair life is. I feel like there is less risk involved in Japanese students’ future plans, which is something that I also follow.