Kofi Christie - NanoJapan 2012

Morehouse College

Major/s: Physics

Anticipated Graduation: May 2015

NJ Research Lab: Prof. Takashi Arikawa, Kyoto University

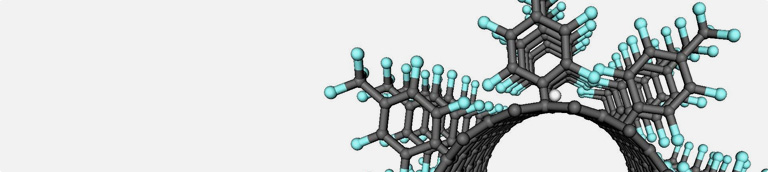

NJ Research Project: Terahertz Time Domain Spectroscopy of Gold Nanorod/Polymer Films

"NanoJapan was the most impactful experience of my entire life. The things I learned from this program transcend academia and culture. I learned about myself. Of course I took home more knowledge on the optical properties of gold nanorods than I could imagine. Of course I learned how to communicate effectively in cross-cultural settings. What I didn’t expect to learn was my threshold for loneliness, or my subtle disdain for prolonged periods of rain. I took for granted how easy it was in America to read each of the ingredients in your food. My experience with NanoJapan taught me how to be independent when nobody is around and how to channel my own fears and discomforts into an urge to learn more." ~ Kofi Christie, Morehouse College

Why NanoJapan?

NanoJapan was obviously a great opportunity for me to get exposed to both physics research and international collaboration. I learned more about gold nanorod properties than I ever thought I would, and I learned how to be an observant team member in the lab. One side of NanoJapan that I think goes overlooked is the value of the program to my research group. Japan maintains an almost intimidating homogeny, and my presence definitely disrupted what everyone was used to in my Japanese host lab. I think my loud and straightforward style forced my lab members to step outside of their comfort zone and adapt to me as much as I was trying to adapt to them. In a place with such well defined social and cultural norms, I was happy to see that my new friends were willing to bend to keep harmony in our relationships.

My goals for this summer were to:

Research Project Overview: Solid-State Spectroscopy Research Group

My research project was observing low frequency vibrational phonons in gold nanorods using terahertz time domain spectroscopy. I was also able to study surface plasmon resonance in the nanorods using ultraviolet-visible-infrared spectroscopy. My research this summer helped me to better understand what a career of physics research involves. I want to pursue physics in a more biology-focused direction in the future, and I think spectroscopy was an excellent place to start. The properties of light absorption are universal and can be applied to any kind of materials research. Also, I can use the knowledge gained this summer in my optics, quantum mechanics, and chemistry courses at Morehouse.

Working in an international research setting presented new cultural challenges every day. I was relieved to find out that the lab was saturated with English texts that needed no translation. In that sense, the physics part of the lab was not unlike studying for tests with friends in America: everyone pooling together what they know to explain why some phenomenon is taking place. The real lab challenges were things like “should I go to lunch with my lab mates today,” “should I try to speak more Japanese this week,” “should I bring back a gift for everyone in the lab,” “when can I ask my professor questions,” and “are they annoyed with me?”

Conducting resaerch in Japan taught me three things: 1) you can’t always trust your instincts, 2) people are willing to help if you smile, and, 3) you will make mistakes regardless of how much effort you put into being “perfect.”

The Tanaka group is made up of dedicated researchers who know their field well and are always willing to help. Each member brought their own personality to the group, but the constant kindness is what I will remember most from everyone. We often went out to eat and we took trips to Arashiyama, Fushimi Inari Shrine, and the famous Gion Matsuri. My lab was full of cool people that I will definitely keep in contact with.

NanoJapan Alumni Follow-on Project

For my follow-on project, I held a workshop discussion through my school’s chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers (NSBE). The workshop highlighted the importance of conducting research as an undergraduate student, especially in an international setting. I helped to expose NSBE members to various international research opportunities in France, Germany, and of course Japan. We hold NSBE meetings about two times a month, so merging my workshop with a NSBE meeting was convenient for both me and our members.

During the workshop, I shared my own NanoJapan experience by expanding on a few of my weekly reports and displaying pictures from the trip. I was asked a lot of questions about Japanese culture and terahertz research. The NanoJapan website was very helpful for this part of the workshop. I also shared the montage of video clips that I captured while in Japan. I’d like to think that the video added a tangible reference to the workshop that allowed 1st year students to really imagine themselves in my shoes. See http://vimeo.com/60221984 for the video clip. Along with the NanoJapan material, I had a table set up at the entrance of the room with brochures to 3 other international research programs.

This workshop took place during the fall semester of 2012, and it was held in a chemistry classroom that accommodates around 100 people. About half of the seats were full, so I estimate that 40 to 60 people were in attendance, with most of them being 1st and 2nd year college students. I made sure that NSBE went the extra mile on refreshments so that the workshop would attract as many students as possible.

I have been posting NanoJapan flyers on the bulletin boards in the Physics department every semester since I returned from Japan. I have talked to 4 Morehouse students about how to apply, what to write on the application essays, and what to expect in the interview. In 2013, Keith (Ron) Hobson, was the second Morehouse College student to be selected into the NanoJapan Program.

Further Research and Future Plans

After researching with the Solid-State Spectroscopy Lab at Kyoto University with NanoJapan, I went on to work with the Environmental Microbiology Lab at Stanford University in the summer of 2013. There, I studied the effects of urban contamination on nitrification rates around the San Francisco Bay. My research at Stanford was hosted by their Summer Undergraduate Research in Geoscience and Engineering (SURGE) Program.

I have also continued to research at Morehouse College with the Micro-Optics Research and Engineering Lab (MORE Lab). We recently traveled to Houston, TX to test a nanosatellite deployment mechanism in micro-gravity conditions. This research project was hosted by NASA at Ellington Air Field, near the Johnson Space Center.

I am on track to graduate a year early, so right now (spring 2014) I am focused on putting together a competitive graduate school application. I would like to pursue a PhD in Environmental Engineering or Applied Physics. In graduate school, I hope to research the fate and transport of pollutants like arsenic in groundwater. In the long term, I would like to use nanotechnology to remediate these pollutants. For example, I would like to fabricate robust polymer membranes to be used as nanofilters in waste water treatment sites and groundwater reservoirs.

Daily Life in Japan

During my stay in Kyoto, I was mostly at the lab during the week and away sightseeing on the weekends. I usually arrived at the lab between 9:30 and 10:30 and stayed until after dinner. My schedule depended on my stage of research, but usually I would read articles in the morning, do experiments in the afternoon, and analyze data in the evening. Toward the end of the summer, when I was running out of money, I would cook in the morning and take Tupperware containers for lunch and dinner. There were four grocery stores and four konbinis between my apartment and Kyoto University, so it was never hard to shop for food.

I was able to travel to Kamakura, Ueno Zoo, Osaka Castle, Nara, Koshien stadium for a Hanshin Tigers game, Hiroshima, Miyajima, Mount Rokko, Kobe, Gion Matsuri, most of the temples and shrines around Kyoto, Mount Koya, and countless other side adventures. I went to many of these places with other NanoJapan members who were either passing through or living near Kyoto. Also, the transportation to and from each of these places was an unexpectedly high investment (since I didn't always use a Rail Pass), so be sure to plan out your trips in advance to make the most of your Japan Rail Pass and other discounted tickets.

Favorite Experience in Japan

Riding my bike through Kyoto on Sundays and finding new/cheap foods to try at the hyaku en shop (cheesy mayo burger bun!?).

Before I left for Japan I wish I had:

Checked out fun things to do in Japan. I could have enjoyed myself more if I planned out some adventures ahead of time. Living day by day is spontaneous, but having at least a loose schedule could have helped me keep sight of my time restraints - and budget.

Pre-Departure Tips

Definitely leave room for souvenirs. Don’t crowd your mind with too many plans and expectations; rather be excited for all the new opportunities to learn.

Orientation Program Tips

First impressions really are everything, so speak carefully, pay attention, and have fun.

Mid-Program Meeting Tips

If you want more time to see southwestern Japan, try to stay with a friend in Kyoto for a few days before or after the meeting. EVERYBODY GO TO THE SANJO BRIDGE AREA FRIDAY AND SATURDAY NIGHTS.

Tips on Working With Your Research Lab

Be careful with jokes, some things translate better than others.

Tips on Living in Kyoto

I purchased and lost/broke four umbrellas in Kyoto, beware of the rainy season. Save some of the Kyoto sightseeing for the Mid-Program Meeting. Kamogawa is a great place to start a random day of bike riding. The grid system of streets are convenient once you realize they exist.

Japanese Language Tips

You will be returned the same amount that you invest. This could be a great opportunity to become comfortably conversational in Japanese.

Other Tips

Gifts: My lab liked things that everybody can grab subtley. Nobody wants to seem like a glutton, so anything small and individually wrapped will be fine. Food gifts were way more popular than lanyards and pens.

Eat: Don’t buy coffee cans from the vending machines; they are cheaper in bulk from the grocery store. Get comfortable cooking as soon as you move into your apartment. It’s fun.

Buy: If being in Japan is a rare opportunity for you, don’t worry about the price tag as much as the potential sustainable memory.

Do: Go to a baseball game!

Visit: Yodobashi camera

Photos and Excerpts from Weekly Reports

Week One - Arrival in Japan: After a four hour flight delay out of Houston International Airport, the

twelve of us were ready to lose half of a day travelling to

Tokyo-Narita. The first thing I

noticed was the size of everything; the beds are much shorter, the

counter tops are much shorter, the chairs are much shorter, etc. I also

noticed that you are more likely to get a smile from someone than a

straight face. Learning Japanese has been a pretty fun experience so far, and I wish I

would have mastered hiragana and katakana before I got to Japan.

Learning sentence structures, vocabulary, particles, and grammar

exceptions are a study in themselves, so not being able to read the

lessons at first just made the classes that much more difficult.

However, most signs and billboards around Tokyo have kanji in them, so

there was really no way I was going to be able to read everything

anyway. My only other exposure to language was taking French classes in

school for seven years. I found that my natural tendency when I didn’t

know a Japanese word/phrase/grammar item was to think of the French

translation. I’m not sure if this is typical, but it was frustrating in

class.

Week Two - Riding the Subway: In Atlanta, there is an extensive train system called the MARTA that is a very good basis for comparison with the Japanese subways and trains. I thought that American college kids were addicted to our ”techno crack,” but Japanese people are outright hooked. It is tough to go into a restaurant, coffee shop, subway station, or any other public place to find people NOT on their cell phones. Even the children have their heads buried in their Nintendo DS’s when out and about. I don’t think it is a case of people not wanting to talk to each other; it seems that people consider it rude to not offer the person next to them a chance at peace and quiet. This inherently requires you to occupy your time with something simple, opportune, and entertaining. On the MARTA, many people might choose to stand even if there is an empty seat next to you. In Japan this does not seem to be the case. For whatever reason, Japanese people seem more comfortable than Americans sitting directly next to each other. I don’t know why American people are less likely to sit down next to you, but it is more practical for a country to not have this predisposition. Maybe the thought process roots back to efficiency, where having empty seats on a train means someone is standing unnecessarily. One core Japanese value that is especially respected on the train is Giri. “Giri may be translated as social obligation. It implies an ethical imperative to behave as expected by the society.” This is definitely observed on the train in the sense that barely anybody (with the exception of maybe high school aged kids) is willing to “rock the boat.” Everybody basically goes with the flow to keep a natural harmonic appearance in society. This was difficult for me to understand at first because I am the type of person to try to change an unfavorable situation, but I now understand that it would be considered rude to put your self interest before the interest of the community. My favorite example of this is how people cross the street in Japan: a business man in a suit will turn on a dead sprint to not get caught in the crosswalk after the little white man on the indicator stops blinking. This is out of courtesy for the drivers. “After all, why should the driver have to wait for you” a Japanese student explained to me. In America, it is rare to see someone sacrifice their suit-wearing dignity to beat a traffic light. I notice that we carry more of an attitude like “the driver only has to wait a few seconds for me, so why run?”

Week 3 - Trip to Minami-Sanriku: Our trip to Minami-Sanriku was very eye-opening for me. The 3/11

earthquake was the most powerful quake in Japan’s recorded history. The

magnitude nine undersea megathrust off the Pacific coast of the Tohoku

region caused enormous waves to crash onto shore, sweeping away cars,

houses, trees, boats, and everything in between. In Minami-Sanriku

specifically, we heard primary source accounts of the floodwaters

reaching over fifteen meters. It is hard to imagine the fear that these

victims would have felt as they witnessed nature take from them all that

they had worked to build. After over a year since the devastation, Minami-Sanriku looked to me

like it had been tsunamified yesterday! I had seen the footage on

YouTube of water taking away vehicles, but I didn’t realize that the

water damage immediately transformed them into junk. I remember most a

parking lot full of compressed cars and trucks that could no longer be

used or sold. That image really allowed me to see that the residents of

Minami-Sanriku couldn’t ever get back what they lost, even if they keep

the memories forever. That scene is the most memorable for me. “If this

is how bad the town looks now, it must have been ten times worse when it

first happened,” I kept thinking to myself. Having never been so close

to the sight of such a disaster, I realized that recovery efforts would

have to be ongoing for decades. The first people we saw in the town were the local elementary school

teachers. They are expected to give energy and happiness (not to mention

prepared lesson plans) to young students who have seen their family

members suffer. They themselves have seen family members suffer, but

they have to be strong, day in and day out, to provide an example for

these kids. I was inspired by their strength. The shopkeepers were

thrilled to have us browse their modest set ups, and it felt good to

contribute to the city’s rehabilitation.

Week 3 - Trip to Minami-Sanriku: Our trip to Minami-Sanriku was very eye-opening for me. The 3/11

earthquake was the most powerful quake in Japan’s recorded history. The

magnitude nine undersea megathrust off the Pacific coast of the Tohoku

region caused enormous waves to crash onto shore, sweeping away cars,

houses, trees, boats, and everything in between. In Minami-Sanriku

specifically, we heard primary source accounts of the floodwaters

reaching over fifteen meters. It is hard to imagine the fear that these

victims would have felt as they witnessed nature take from them all that

they had worked to build. After over a year since the devastation, Minami-Sanriku looked to me

like it had been tsunamified yesterday! I had seen the footage on

YouTube of water taking away vehicles, but I didn’t realize that the

water damage immediately transformed them into junk. I remember most a

parking lot full of compressed cars and trucks that could no longer be

used or sold. That image really allowed me to see that the residents of

Minami-Sanriku couldn’t ever get back what they lost, even if they keep

the memories forever. That scene is the most memorable for me. “If this

is how bad the town looks now, it must have been ten times worse when it

first happened,” I kept thinking to myself. Having never been so close

to the sight of such a disaster, I realized that recovery efforts would

have to be ongoing for decades. The first people we saw in the town were the local elementary school

teachers. They are expected to give energy and happiness (not to mention

prepared lesson plans) to young students who have seen their family

members suffer. They themselves have seen family members suffer, but

they have to be strong, day in and day out, to provide an example for

these kids. I was inspired by their strength. The shopkeepers were

thrilled to have us browse their modest set ups, and it felt good to

contribute to the city’s rehabilitation.

Week 4 - First Week in Research Lab: When I arrived into the Kyoto shinkansen station on Sunday night, I reached into my pocket and was shocked to see on my phone nine missed calls from Arikawa-san, my research supervisor… great start. But then we went out to eat, he helped me get settled at my apartment, we toured around Kyo Dai’s campus, I received my bike, and everything went well after that… until I got lost in Kyoto Monday morning and spent three hours riding around hopelessly! I eventually saw a familiar kombini (they surprisingly don’t all look the same) and made it to the lab. I am very grateful to have a research supervisor who laughed at the story instead of frown. “What happened to the map I gave you,” he teasingly asked? From there I was introduced to everyone in sight, but there was a lot of moving around because I came in during the lab cleaning period. Everyone introduced themselves in English and they were surprised that I was able to introduce myself in Japanese. Naka-san, an associate professor, gave me a tour of the experiment rooms and quick explanations of how everything worked. I went to lunch with the lab group; the cafeteria was pretty much exactly what I expected: similar to my lunch room at school in the format, but different in the foods, the pace of everything, and the mannerisms. Before we ate, we all positioned our hands in front of us and said ittadakimasu. After we ate, we did the same thing and said goicho so samadeshita. I have started the initial equipment training related to my project, and the three of us (me, Dr. Searles, and Arikawa-san) are on the same page. The goals are defined but I can see that there is room for me to do more than what we are planning. I was also lucky enough to attend a lecture by Professor Peter Uhd Jepsen from Denmark in which he discussed a more accurate alternative to micro four point probing by using terahertz radiation. This technique is used to map the conductivity of graphene on a semiconductor. After the presentation, Tanaka-san led me and the presenters on a tour of Kyoto University’s high-tech labs where I was able to see a lot of cool machinery that I don’t know how to use. My research mentor is Yuji Hazama and he is extremely helpful. His English seems to be the best in the lab group so it is very easy to ask him questions in either language. A few of us went out to dinner at a Korean barbecue restauraunt and he introduced me to roasted beef tongue (totemo oishikatta desu). A few of the lab members aren’t as comfortable speaking English, and I noticed that they haven’t reached out to me as much. I made the effort to ask them questions in my elementary Japanese and they were more than willing to help. Enough people speak English for me to not worry about being confused or misunderstood while I am here. Although it takes a few extra minutes to whip out the handheld translator, we are all patient enough to make it work.

Week 4 - First Week in Research Lab: When I arrived into the Kyoto shinkansen station on Sunday night, I reached into my pocket and was shocked to see on my phone nine missed calls from Arikawa-san, my research supervisor… great start. But then we went out to eat, he helped me get settled at my apartment, we toured around Kyo Dai’s campus, I received my bike, and everything went well after that… until I got lost in Kyoto Monday morning and spent three hours riding around hopelessly! I eventually saw a familiar kombini (they surprisingly don’t all look the same) and made it to the lab. I am very grateful to have a research supervisor who laughed at the story instead of frown. “What happened to the map I gave you,” he teasingly asked? From there I was introduced to everyone in sight, but there was a lot of moving around because I came in during the lab cleaning period. Everyone introduced themselves in English and they were surprised that I was able to introduce myself in Japanese. Naka-san, an associate professor, gave me a tour of the experiment rooms and quick explanations of how everything worked. I went to lunch with the lab group; the cafeteria was pretty much exactly what I expected: similar to my lunch room at school in the format, but different in the foods, the pace of everything, and the mannerisms. Before we ate, we all positioned our hands in front of us and said ittadakimasu. After we ate, we did the same thing and said goicho so samadeshita. I have started the initial equipment training related to my project, and the three of us (me, Dr. Searles, and Arikawa-san) are on the same page. The goals are defined but I can see that there is room for me to do more than what we are planning. I was also lucky enough to attend a lecture by Professor Peter Uhd Jepsen from Denmark in which he discussed a more accurate alternative to micro four point probing by using terahertz radiation. This technique is used to map the conductivity of graphene on a semiconductor. After the presentation, Tanaka-san led me and the presenters on a tour of Kyoto University’s high-tech labs where I was able to see a lot of cool machinery that I don’t know how to use. My research mentor is Yuji Hazama and he is extremely helpful. His English seems to be the best in the lab group so it is very easy to ask him questions in either language. A few of us went out to dinner at a Korean barbecue restauraunt and he introduced me to roasted beef tongue (totemo oishikatta desu). A few of the lab members aren’t as comfortable speaking English, and I noticed that they haven’t reached out to me as much. I made the effort to ask them questions in my elementary Japanese and they were more than willing to help. Enough people speak English for me to not worry about being confused or misunderstood while I am here. Although it takes a few extra minutes to whip out the handheld translator, we are all patient enough to make it work.

Week 5 - Critical Incident Analysis: I have lots of little stories from where something went differently than I expected as a result of being in a new place for such a short period of time. These range from getting lost, to mixing up names, to forgetting regular meeting times. However, just recently I endured a series of conversations that were strictly a result of cultural ignorance. So tomorrow is a campus wide holiday for Kyoto University; it is the universities “founding day,” where classes are cancelled to acknowledge the school’s rich legacy. The school was actually founded on May 1, 1869, but it was chartered on June 18, 1897. On Friday, my advisor told me that Monday is a holiday and that I don’t have to come in to the lab. I figured it must be significant because later that day, two separate lab members also told me that I didn’t have to come in. I went on through the day appreciating the three-day weekend because I recently came down with a cold and could really use the extra sleep (I’m clocking in about 15 hours a day!). That night, I realized there may be a misunderstanding. After a physics related discussion/party/poster presentation (the Lorentz festival), I decided to ask my lab mates if people actually take days off. They admitted that about half of the lab might be in for work on Monday, to my surprise (why would you come in on a day off??). So I asked members individually and nearly everybody said they were coming in on Monday with full knowledge of the holiday. The members who decided to skip Monday said that they were coming in on Saturday to make up for it! I basically learned that holidays don’t mean anything to a work schedule, and many Japanese people are culturally committed to two-day-only weekends. I guess it’s an unspoken rule or courtesy to follow your supervisor’s example, and none of the higher-up lab members are planning to take a three-day weekend. This little cultural example speaks a lot about Japanese people as a whole. 1) The plans were all indirect, meaning nobody had to tell anybody else to come in to work on Monday. They all just knew the deal inherently. 2) Contributing maximum effort is expected in Japanese society. Why should you take an extra day off if you can sense that nobody else is? I understand that everybody wanted to be polite and offer me the extra day off, but perhaps my lab mates don’t yet see me as a member of the lab. More likely, I am the “American extended visitor” who needs a three-day-weekend every once in a while. I definitely would have appreciated if they said something like, “Kofi-san, Monday is a holiday celebrating the founding of Kyodai. You are free to take an extra day off, but most of us will come in to work anyway.” But maybe it’s asking too much for them to acknowledge my ignorance of Japanese tradition. Maybe they assumed everybody in America comes in to work on holidays. Or maybe they really do want me to relax and reflect on my first couple of weeks. This situation left me very confused about where I fit into the lab’s group and what my lab members think of me. Should I come in to work on Monday to show my dedication? Should I stay home and rest more? Should I ask somebody what to do? Do they expect me to come in to work? Do they expect me to stay home? Could I come in for half a day? The indirectness is killing me!

Week 6 - Research in Japan vs. the U.S.: Some of the rules of the lab that I have noticed revolve around the oh-so-Japanese concept of team rather than self. It is customary for the PhD students and post docs to attend presentations hosted by the masters students. Many times it seems like they are already very familiar with the content of the presentation, but they still attend to promote the image of “team.” They will ask penetrating questions and engage the presenter in order to help them think more deeply about their topic. I don’t know whether or not this is the case in American grad programs, but it definitely supports a comfortable learning atmosphere for everybody. I also noticed that everyone in my lab is quick to drop what they’re doing to help out someone else. If we are all sitting in the computer room quietly typing away, nobody would hesitate to break the silence to ask a question to their peers. Each lab member treats each other lab member’s problem as if it were their own priority; once again displaying a strong sense of team. Also, if someone was ever annoyed by the timing of a lab member’s question, they would never show it. From what I have noticed, the only traits shown openly by Japanese people are happiness and patience. I would venture to say that the only way to tell what a Japanese person is feeling is to be Japanese. Another general rule might be conversation structure. When speaking English in America, the speaker often likes to see confirmation that the listener is following along with what they are saying. I might nod my head every few sentences to assure a teacher that I understand what’s going on. This is not enough when speaking Japanese in Japan; the listener literally interjects with little sounds of confirmation, “Hai.. hai.. so so so.. hai.. hai.. hai..” This caught me off guard at first, because my lab mates also do this in English whenever I am speaking. When I ask them why they do it, that question catches them off guard because that is just how people naturally exchange in Japan. I am curious to know whether or not it is rude for a Japanese person to not give these little guarantees of attention. Would that make them seem uninterested? When speaking English in America, it is common for the listener to not even look at you when speaking. When I was younger I would demand my dad’s attention while he was trying to do something else (watch TV, send an email, etc). I would get upset when he wasn’t watching me speak to him and his favorite response was always, “I LISTEN WITH MY EARS not my eyes!”

Week 7 - Preparing for the Mid-Program Meeting: I’m proud to say that I’m now very comfortable navigating the streets around Kyodai on a bike. I’ve gone home from my lab at least 6 different ways since I’ve been here. I can basically find my way around using landmarks and a compass. Granted, Kyoto’s grid-like city structure doesn’t make it very difficult, but I’ve come a long way from riding around lost for three hours… true story. My biggest personal challenge right now is noticing all the good things around me before noticing the bad things. For example, if my mom calls and asks me how I’m doing, I might tell her stories about when I’ve been unhappy (stuck in the rain with no umbrella, took the train in the wrong direction, etc.). I strive to be the kind of person who mostly sees a positive side of everything. There’s no need to relive what makes you sad; experiencing it the first time should have been enough! This is especially true when I’m lucky enough to be a part of an awesome new experience in an awesome new place. I am progressing as anticipated. However, there is a temporary lack of availability with our equipment. The THz pulse system in the lab is not working correctly right now, and I am waiting until it gets repaired to begin training with a grad student. I am not sure whether it will be fixed sooner or later, but there is another machine at a different building on campus that I will be able to use this week.

Week 7 - Preparing for the Mid-Program Meeting: I’m proud to say that I’m now very comfortable navigating the streets around Kyodai on a bike. I’ve gone home from my lab at least 6 different ways since I’ve been here. I can basically find my way around using landmarks and a compass. Granted, Kyoto’s grid-like city structure doesn’t make it very difficult, but I’ve come a long way from riding around lost for three hours… true story. My biggest personal challenge right now is noticing all the good things around me before noticing the bad things. For example, if my mom calls and asks me how I’m doing, I might tell her stories about when I’ve been unhappy (stuck in the rain with no umbrella, took the train in the wrong direction, etc.). I strive to be the kind of person who mostly sees a positive side of everything. There’s no need to relive what makes you sad; experiencing it the first time should have been enough! This is especially true when I’m lucky enough to be a part of an awesome new experience in an awesome new place. I am progressing as anticipated. However, there is a temporary lack of availability with our equipment. The THz pulse system in the lab is not working correctly right now, and I am waiting until it gets repaired to begin training with a grad student. I am not sure whether it will be fixed sooner or later, but there is another machine at a different building on campus that I will be able to use this week.

Photo of me at Koya-san

Week 8 - Reflections on Japanese Language & Culture: My most challenging linguistic experience has been in the grocery stores around Kyoto. I go to a 24-hour store called Fresco two times a week, and it is not nearly as “English-friendly” as many of the other public places I’ve been to. I go in looking for specific items like butter, strawberry jam, and frozen peas. It can be confusing because some of the food is commonly referred to by its English name, but Japanese-English is never the same as American English… I will ask one of the workers for “butter,” and he will have no idea what I’m talking about. Then he will grab a co-worker to help translate the foreign word, but it results in two confused store clerks repeating, “hmm… butter? Buudder? Hmm… gomenasai! I don’t know…” Then perhaps a third person will intervene and say, “Ahh! Bah-tah! Kochira!” and they will lead me to the ever elusive dairy section of the store. Pronunciation is everything, and the simplest words seem unintelligible without the Japanese accent strongly attached. It’s always pretty funny when my American accent on an English word goes misunderstood in Japan! These situations helped me to understand that English words are not really English words to some Japanese people; rather they are guidelines for how the Japanese equivalent should sound. One can compare Japanese English to Australian or British English. They words may be written the same, but they are morphed to match that society’s speech system.

Week 9 - Critical Incident Analysis in the Lab: This past weekend my lab mates took me to Arashiyama on the west side of

Kyoto. We went to a great unagi restauraunt, climbed to the peak of

saruyama (monkey mountain), and visited the suzumushi tera (buzzing

insect temple). Afterward we went back to central Kyoto for the famous

Gion Matsuri. It turned out to be a fun weekend, but the planning stage

was confusing for me.

My lab mates and I had been throwing schedules around since early June,

but nobody really wanted to take charge and suggest things to do. “So

Kofi-san, do you have fun things planned for this weekend?” I usually

did have fun things planned for the weekend, but I was free maybe a

quarter of the time. There is a fine line between ambivalence and

politely relinquishing the power to choose. I wasn’t sure if my lab

mates didn’t care about where we went or if they were just giving me the

decision to be polite. Bear in mind that I have no idea what’s fun to

do around the city. It was difficult for my lab mates to suggest a place

to go because they wanted me to have the option to go wherever I wanted

to go (or maybe they were just that versatile). Eventually they chose

Arashiyama and we had a great time. I wish we didn’t have to go through

the whole indirect tango before they chose a cool spot. Knowing that I

am in a culture different from what I’m used to makes me overanalyze

these would-be-nuances.

At the end of the day we are all people, and we all have preferences. In

the Japanese/human quest for harmony, it seems like people also have

the desire to succumb to everyone else’s preferences. This can be very

tricky in a situation where everyone wants to say yes, because whoever

suggests a plan is giving up the opportunity to be polite to everyone

else by agreeing. You can’t really politely agree to your own

suggestion. This is super meta…

Week 9 - Critical Incident Analysis in the Lab: This past weekend my lab mates took me to Arashiyama on the west side of

Kyoto. We went to a great unagi restauraunt, climbed to the peak of

saruyama (monkey mountain), and visited the suzumushi tera (buzzing

insect temple). Afterward we went back to central Kyoto for the famous

Gion Matsuri. It turned out to be a fun weekend, but the planning stage

was confusing for me.

My lab mates and I had been throwing schedules around since early June,

but nobody really wanted to take charge and suggest things to do. “So

Kofi-san, do you have fun things planned for this weekend?” I usually

did have fun things planned for the weekend, but I was free maybe a

quarter of the time. There is a fine line between ambivalence and

politely relinquishing the power to choose. I wasn’t sure if my lab

mates didn’t care about where we went or if they were just giving me the

decision to be polite. Bear in mind that I have no idea what’s fun to

do around the city. It was difficult for my lab mates to suggest a place

to go because they wanted me to have the option to go wherever I wanted

to go (or maybe they were just that versatile). Eventually they chose

Arashiyama and we had a great time. I wish we didn’t have to go through

the whole indirect tango before they chose a cool spot. Knowing that I

am in a culture different from what I’m used to makes me overanalyze

these would-be-nuances.

At the end of the day we are all people, and we all have preferences. In

the Japanese/human quest for harmony, it seems like people also have

the desire to succumb to everyone else’s preferences. This can be very

tricky in a situation where everyone wants to say yes, because whoever

suggests a plan is giving up the opportunity to be polite to everyone

else by agreeing. You can’t really politely agree to your own

suggestion. This is super meta…

Week 10 - Career Interview: This week I had the opportunity to ask Associate Professor Nobuko Naka a few questions about her perspective on the career of a Japanese researcher. My conversation might have been especially rare because she is one of the few women in her position today. Naka-sensei grew up enjoying math and science and decided to pursue physics research after an early exposure to superconductors her senior year of high school. She then went on to obtain a bachelors, masters, and PhD in physics. She reminded me not to get so focused on one goal that I neglect other possible directions in life. In fact, three months into her PhD program, she left to work in industry before deciding to come back to research. Since then, Naka sensei has been a devoted researcher and professor. I commented on what I had noticed so far in Japanese students: Although all students around the world have the capacity to achieve whatever they want in academia, Japanese students tend to exert a larger portion of their daily energy to achieving these goals. Naka sensei agreed and admitted that there is a lot expected from you as a Japanese student/researcher, and most people are eager to meet and exceed these societal expectations. During her research career, Naka sensei has been able to travel to and present work at various conferences around the world in countries like Canada, France, and Finland. She has contributed to international research in a German laboratory for some months as well. On the topic of international research, Naka sensei explained that although laboratories in Germany and Canada may be very different from those in Japan, the different research labs within Japan itself can be very different. She spent some time collaborating with a chemical engineering lab in Japan (Tokyo University) and found it to be more “professional” and less “friend/family” oriented than the Tanaka group. Naka sensei enjoys having international students around the Kyoto University campus because it helps to show young people that the whole world is not Japan. The comfortable homogeny does not last for long outside of these borders, so interaction with non Japanese people will only help the students here. She has also been generally impressed by the energy of the international students that she has worked with. She is disappointed by the attention that international students get at Kyoto University; she cites a recurring example where important clerical notices will not be sent directly to international students, but rather a Japanese teacher. In the case of Japanese students, they would directly receive these notices. With her 15 years of teaching and research experience, Naka sensei plans to continue her work exactly the way she has been. She wishes to see more women in the hard science research fields and more international people in Japan.

Week 11 - Final Week in Japan: I realized this summer that true observations are made over time. People are not consistent in their personality if you notice them hourly or even daily. A person’s actual personality comes out when you look back on what they do consistently for months. Also, the effects of a person’s behavior can’t be judged in a short period of time. I initially thought that information moved very slowly in Japan due to the great efforts taken to remain polite. Instead of showing someone why they were wrong, a Japanese professor might bend their words to make the person show themselves why they were wrong. In my mind, this just delayed the inevitable end scenario, and everything between the question and the answer was wasted time. In reality, this technique keeps harmony in the relationship between the two disagreeing parties. Keeping harmony is valuable because it prevents either person from becoming overly stressed or emotional. I had to learn that this method works better for many people who are used to Japanese culture, and it may even be a solution that I should consider applying to my disagreements in the future. The United States seems much less emotionally invested in the group’s well being. I thought we were concerned about each other to a great extent, but I learned that one of our main motivations is achieving the highest level of efficiency in any situation. This efficiency often trumps harmony, and that often leads to one person being upset or unwilling to disagree in the future. After working in Japan, I am not so sure that efficiency should be placed on such a high pedestal. I will miss most about Japan that I was able to learn something new every day about a culture that I was very fascinated by. It’s one thing to read about Japanese culture on the internet, but it’s a whole other experience to hear first-hand why people apologize before asking an insightful question, run when crossing the street, and refrain from eating salmon onigiri with shoyu. These first-hand factoids were always at a short distance in Japan, and I will miss having people close to me that are capable of providing them. This experience allowed me to really see how much background knowledge is necessary to pose relevant research questions. Having an observation or question is the first step to contributing to any field in science. This may be why Japanese researchers wait until a student has taken many courses (fourth year) before offering them lab research positions. For my final week in Japan, I worked harder than I had worked all summer to finish my project poster. My lab mates were very supportive of my newfound energy and quizzed me on phonon properties in gold nanorods. I couldn’t tell if they were actually curious about my topic or if they were just making sure that I was able to explain it clearly… Either way it was very helpful. On the Thursday before I left the lab, we had an okonomiyaki and takoyaki party. My lab mates are very good about hiding plans from me because I had no idea when they went out and bought all the food ingredients. Basically, one morning the fridge was messy and unkept, then that afternoon it was perfectly organized with two heads of cabbage and octopus tentacles! At the party, they presented me with a dark blue jimbe as a going away present. I was happy to receive it, and on my final day I gave them all hand written notecards with my reflections on each of our relationships over the summer. I was able to share some pretty funny inside jokes with many of them (origami-san, “I am yoshikawa-san, look at my shirt,” mukai-sensei, onishi-san-never-leaves-lab, hyoooodooooo-san). I plan to keep in touch with my lab as frequently as possible and to continue my gold nanorod investigations at Morehouse this fall. I climbed Mount Fuji with the other NanoJapan students on the final weekend, and prepared for our flight back to America. I was not at all shocked to notice that my circadian rhythm was more tangled than my newly acquired untrimmed afro.